Between Codicology and Legal History: Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Between Codicology and Legal History: Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

Between Codicology and Legal History: Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

Frank Soetermeer

D the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a great many pecia manuscripts were produced at universities in Italy, France, and England, many of which survive in

public libraries all over Europe. Although there are no statistics on the number of extant manuscripts, there are sure to be several thousand. With some exceptions, I believe that most manuscripts of the basic texts of law, theology, and medicine—in great de-mand by students—were produced under university auspices and were in fact pecia manuscripts, although this is often difficult to prove. This article will describe the organization and procedures involved in pecia manuscript production (with special emphasis on legal manuscripts produced in Bologna), complemented by an overview of previous scholarship on this subject.

T

The pecia, or piece, was the essential element in the type of book production nowadays called the pecia system, an easy and rapid method for producing and disseminating texts. Copying texts was (and still is) a very lengthy task. If the text copy from which the medieval scribe derived his own copy had been bound as a sin-gle book, then during the period it was being copied it would have been unavailable for use by others. For this reason texts were cop-

. This article is an expansion of a paper given at the “Groninger Codicolo-gendagen” at Leeuwarden in the Netherlands and is for the greater part based on: Frank Soetermeer, Utrumque ius in peciis: Aspetti della produzione libraria a Bolo-gna fra Due e Trecento, this Italian edition translated from the Dutch by Giancarlo Errico (Milan, )—hereafter Soetermeer (); and the German edition trans-lated from the Dutch by Gisela Hillner: Utrumque ius in peciis: Die Produktion ju-ristischer Bücher an italienischen und französischen Universitäten des . und . Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt am Main, )—hereafter Soetermeer ().

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

ied from the loose quires of a still unbound book. This proce-dure had been previously utilized not only in monastic scriptoria, but also, in all probability, at secular centers of learning—the so-called studia—during the twelfth century. At that time the univer-sity as an organization did not yet exist. As the demand for basic texts grew, bookshop owners began to make a habit of stocking copies that were not intended for study, but only to serve as mod-els for copyists. Such a model was called an exemplar (sometimes exemplum). Exemplaria (henceforth exemplars) were always pro-duced in a simple manner. They were written on inexpensive parchment in an unpretentious and non-calligraphic script and were kept unbound. The loose gatherings or quires of which they were composed were called “pecias,” literally, “pieces.” Some exemplars (surviving today as bound books) have been preserved, comprising theological, philosophical, medical, and legal texts, this last category constituting over forty percent of the total.

The men who owned the exemplars and rented them out to the copyists were called stationarii. Although a statio could be any kind of shop, workshop or office, the word stationarius was only used for persons who were involved in book production and the book trade. In Italy stationers, as I will call them, were either men whose only role was writing and renting pecias (stationarii pe-ciarum, stationarii exemplariorum), or book brokers who acted in the first place as mediators between sellers and buyers of books:

. No less than of them were found by Jean Destrez, whose work will be dis-cussed below. After his death a list of them was published in Jean Destrez and M.D. Chenu, “Exemplaria universitaires des XIIIe et XIVe siècles,” Scriptorium (): –. Recently a description of exemplars of legal texts, of which are more or less complete, while the others are single pecias, was published by Giovanna Murano, “Tipologia degli exemplaria giuridici,” in Juristische Buchproduktion im Mittelalter, ed. Vincenzo Colli (Frankfurt am Main, ), –, esp. –. See also Giulio Battelli, “Osservazioni sull’exemplar,” in La Production du livre uni-versitaire au moyen âge: Exemplar et pecia. Actes du symposium tenu au Collegio San Bonaventura de Grottaferrata en mai , ed. Louis J. Bataillon, Bertrand G. Guyot, and Richard H. Rouse (Paris, ), –, and “Il libro universitario,” Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria (): –; Stefano Zamponi, “Ex-emplaria, manoscritti con indicazioni di pecia e liste di tassazione di opere giu-ridiche,” in La Production du livre universitaire au moyen âge, –; Giovanna Murano, Manoscritti prodotti per exemplar e pecia conservati nelle biblioteche aus-triache (Vienna, ), –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

they sold second hand books, but were at the same time lessors of pecias (stationarii librorum).

The basis of the pecia system was that exemplars were rented out one pecia at a time. When the scribe had finished copying a pecia, he went to the stationer and exchanged it for the following unit and then continued his work. Another important element is that—just as in modern public libraries—the lending time was restricted. Most medieval university statutes contain regulations on the book production and book trade. Sometimes these rules are very brief, and in other cases very detailed, especially the Bo-lognese examples. Although very few of them indicate how long a copyist could keep a pecia, the period when mentioned was al-ways a week. Apparently this length of time was considered so much the norm that it was either not thought necessary to specify this in the statutes—or else it was simply overlooked.

. On this terminology, see further Olga Weijers, “Stationarius, Librarius, Peci-arius, Exemplator(-arius), Scriptor, etc.,” in Terminologie des universities au XIIe siècle, ed. Olga Weijers (Rome, ), –, and F.P.W. Soetermeer, “La terminol-ogie de la librairie à Bologne aux XIIIe et XIVe siècles,” in Actes du colloque Termi-nologie de la vie intellectuelle au moyen âge: Leyde/La Haye - septembre , ed. Olga Weijers (Turnhout ), –; Louis J. Bataillon, “Exemplar, pecia, qua-ternus,” in Vocabulaire du livre et de l’écriture au moyen âge: Actes de la table ronde, Paris – septembre (Turnhout, ), –; Mariken Teeuwen, “The Vo-cabulary of the Book and Book Production,” in The Vocabulary of Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages, ed. Mariken Teeuwen (Turnhout, ), –.

. Concise introductions to the book production at the medieval universi-ties are given in the chapters by Susan L’Engle in Susan L’Engle and Robert Gibbs, Illuminating the Law: Legal Manuscripts in Cambridge Collections (Turn-hout, ). Another brief outline is found in Hugues V. Shooner, “La Production du livre par la pecia,” in La Production du livre, –. See also Gero Dolezalek, “La pecia e la preparazione dei libri giuridici nei secoli XII–XIII,” in Luoghi e metodi di insegnamento nell’Italia medioevale (secoli XII–XIV): Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi Lecce-Otranto – ottobre , ed. Luciano Gargan and Oronzo Limone (Galatina, ), –; Giovanna Murano, “Opere diffuse per exemplar e pecia: Indagini per un repertorio,” Italia medioevale e umanistica (): –. Slightly outdated is Graham Pollard, “The Pecia System in the Me-dieval Universities,” in Medieval Scribes, Manuscripts and Libraries: Essays Pre-sented to N.R. Ker (London, ), –. For theological texts see, for example, Gordon A. Wilson, “Preliminary Indications of a Historical Development in the Second Parisian Exemplar of Henry of Ghent’s Quodlibet VI,” in Proceedings of the Patristic, Mediaeval and Renaissance Conference (Villanova, Penn., ), –; Raymond Macken, “The Possible First Exemplar of the Articles – of Henry of Ghent’s «Summa»,” Medioevo (): –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

Whatever the organizational criteria, the pecia system had great advantages. Since a copyist utilized only one pecia at a time and not the entire text, only this single unit was temporarily in-accessible to other scribes, and this only for a week. All other pe-cias of the text were available to his colleagues. Thus, for example, if an exemplar consisted of forty pecias, in theory forty individu-als could copy it simultaneously, or forty copies of the text could be produced at once. In reality this number was always a bit lower, but notwithstanding, this system considerably simplified and ex-panded the production of scholarly books and as a result also pro-moted the dissemination of the disciplines taught at the medieval universities. In the case of law, this meant that the pecia system contributed to the penetration all over continental Europe (and to a much lesser degree in England) of the doctrines that had been developed at the medieval universities and which were based on texts of civil (Roman) and canon law.

Normally a pecia consisted of four folios (called duerni in the terminology of medieval book production). In France, however, pecias were sometimes quires of not four but six (terni), or twelve folios (sexterni), or otherwise just a bifolium. In Italy a pecia some-times consisted of eight (quaterni) or sixteen folios (octerni). To enable the copyist to find the pecia he needed, the pecias of an ex-emplar were always numbered. The copyists noted these numbers in the margins of the texts they were writing. Such notes are called pecia marks. In France and England the copyists usually noted the beginning (“incipit va. pecia”); in Italy they registered the end (“finitur ia. pecia” or “finis iie. pecie”). Giovanna Murano, who has studied many exemplars, thinks that the reason for the different practices between France and England on the one hand, and It-aly on the other, is very simple: in French exemplars the number of the pecia was normally written on the first page and in Italy on the last one. This idea seems plausible. Sometimes the name of the stationer who owned the pecia is mentioned on the first or the last leaf, but unfortunately this is rather rare.

In the modern literature on university manuscripts, pecia notes are sometimes called explicit pecia marks, to distinguish

. Murano, “Tipologia,” .

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

them from the so-called implicit pecia marks. This latter term is used for all sorts of visual anomalies in the text that demon-strate that the copyist has interrupted his work to go to the statio-ner and exchange the pecia he had just finished for the following one. Before continuing his writing he would sharpen his pen, and his letters would then suddenly become thinner—or he would fill his inkpot so that his text would abruptly become either darker or lighter. When such elements are located at exactly the same place where other manuscripts present an explicit pecia mark, we can be sure that the manuscript is indeed a pecia manuscript, al-though it presents no (explicit) pecia marks at all.

Sometimes the pecia a copyist needed, number five, for in-stance, was not available at that moment. He would then copy in reverse order: taking pecia number six, he would leave blank the amount of space he thought would be needed for number five. Obviously such calculations never agreed with the space that was actually required. At times the scribe had overestimated the length of the pecia and there would be an ugly gap left in the text, which his client would hate. As penance he would fill it by copy-ing the last part of the pecia once again and would then immedi-ately suppress this part of the text by adding “va” at the beginning and “cat” at the end: “vacat,” meaning “this is empty.” In the oppo-site case, when he had underestimated the space, he would write the surplus in the lower margin. Finally, there were also copyists who simply left the missing portion out, in this way contributing to the ill repute of copyists among medieval scholars.

R

The first person to point out that the sixteenth-century statutes of the University of Bologna contained regulations on the pe-cia was Friedrich Carl von Savigny (–), the most famous and influential legal historian of the nineteenth century. These statutes were a revised version of older, medieval statutes, and

. See for example Jos Decorte, “Les Indications explicites et implicites de pièces dans les manuscrits médiévaux,” in La Production du livre, –.

. An example is found in Jean Destrez, La Pecia dans les manuscrits universitaires du XIIIe et XIVe siècle (Paris ), Pl. .

. Ibid., –, and for an example, Pl. .

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

many of their precepts had become completely obsolete. Savi-gny addressed this question in an important work on the learned lawyers of the Middle Ages. However, as his only source of infor-mation was these statutes, and he seems never to have seen any pecia manuscripts, he did not quite understand what this proce-dure implied.

A better understanding of the pecia system only came about at the beginning of the twentieth century, thanks to the editors of the works of Thomas Aquinas, who were of course theologians. One of them, the Dutch Dominican Constantius Suermondt, called at-tention in his introduction to the so-called pecia marks he had found in the margins of two of the manuscripts he had used for his work on the Leonine edition. He was the first editor of a me-dieval text to do so. Another, Jean Destrez (–), became so engrossed with this topic that he studied pecia manuscripts very thoroughly. Having examined around thirteenth- and fourteenth-century manuscripts for traces of the pecia, in he communicated his findings in La Pecia, a remarkable and pio-neering study that was also the first publication entirely devoted to the subject. It was meant as an introduction to several volumes containing descriptions of the one thousand pecia manuscripts he had found that he intended to publish, although due to various circumstances this project was never realized. La Pecia, however, received a good deal of attention, garnering no less than thirty-four reviews within a year. In Karl Christ discussed the book in great detail, not only publishing some interesting supplemen-tary data but also casting doubt on some of Destrez’s supposi-tions. This article is still well worth reading. It was taken as a point of departure by Guy Fink-Errera, whose study on the

. Friedrich Carl von Savigny, Geschichte des römischen Rechts im Mittelalter, vols. (Heidelberg, ; repr. Goldbach ), :–.

. See Tertia Pars Summae Theologiae a questione LX ad quaestionem XC, vol. of Sancti Thomae Aquinatis doctoris angelici Opera omnia iussu impensaque Leo-nis XIII P.M. edita (Rome ), praefatio in supplementum tertiae parties, ix–xi; see also: Summa contra gentiles, vol. of Sancti Thomae Aquinatis doctoris angel-ici Opera omnia iussu impensaque Leonis XIII P.M. edita (Rome ), xxvii-xxx. These introductions are attributed to Suermondt by Destrez in La Pecia, .

. See n. .. Karl Christ, “Petia: Ein Kapitel mittelalterlicher Buchgeschichte,” Zentralblatt

für Bibliothekswesen (): –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

pecia system also formulated a remarkable but not very convinc-ing hypothesis on the way texts were published at the medieval universities. This Belgian scholar took up Destrez’s scholarly legacy and prepared an edition of his notes, the publication of which was prevented by his untimely death in .

O

As Destrez was a theologian, it is understandable that the univer-sity manuscripts he knew the best were theological texts. These were very often written in Paris, sometimes at universities in southern France, or in Oxford, and rather rarely in Italy. Destrez’s reasoning was in fact strongly based on the situation in Paris. The fact that he incorrectly generalized and applied his conclu-sions to all universities is pardonable, as there was (and still is) rather a general tendency to see the University of Paris as by far the most important center of higher education of the Middle Ages, which therefore would obviously have served in every re-spect as a model for all other Studia. However, I am convinced that the pecia system originated in Bologna; Richard and Mary Rouse, authorities on book production in Paris, appear to share

. Guy Fink-Errera, “Une institution du monde médiéval: La «pecia»,” Revue phi-losophique de Louvain (): –, translated into Italian (with some omis-sions) as “La produzione dei libri di testo nelle università medievali,” in Libri e lettori nel medioevo: Guida storica e critica, ed. Guglielmo Cavallo (Rome, ), –, –. I criticized his theory in Soetermeer (), – and Soeter-meer (), –.

. For the functioning of the pecia system in Paris, see Richard H. and Mary A. Rouse, “The Book Trade at the University of Paris, ca. –ca. ,” in La Produc-tion du livre, –, reprinted in Mary A. and Richard H. Rouse, Authentic Wit-nesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts (Notre Dame, Ind., ), –, and “The Dissemination of Texts in Pecia at Bologna and Paris,” in Ra-tionalisierung der Buchherstellung im Mittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit: Ergeb-nisse eines Buchgeschichtlen Seminars, Wolfenbüttel, – November , ed. Peter Rück and Martin Boghardt (Marburg an der Lahn, ), –. See on Parisian book production in general Richard H. and Mary A. Rouse, Manuscripts and their Makers: Commercial Book Producers in Medieval Paris –, vols. (Turn-hout, ).

. On the other hand, Destrez also made the incorrect assumption that particu-larly Italian establishments such as the peciarii—who controlled the book produc-tion in Bologna—were in effect everywhere.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

this opinion. This technique of production was adopted later on at already-existing universities such as Paris and Oxford, as well as at the various new ones that came into being in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The pecia system arose during the first quarter of the thir-teenth century, and it seems to be no coincidence that the begin-ning of the thirteenth century was exactly the period in which the Bolognese university was beginning to take shape. This does not mean that up to then no higher education had existed there. Like Paris, Bologna had had a studium for about a century, but when a city was known to house a studium this only signified that some illustrious scholars were teaching there, not specifically in the liberal arts but in one of the higher disciplines. In the previous century, however, neither the professors nor their students had formed academic associations, and only in the course of the thir-teenth century did some types of university organizations begin to develop. As the saying goes, Bononia docet: the Bolognese Alma Mater led the way. Here, not the professors but the students were the first to band together in an alliance, the universitas scolarium. For more than a century the University of Bologna was truly an institution where students imposed regulations on the professors, rather than the contrary. In Paris, however, and somewhat later, it was the professors who organized an association, the universitas magistrorum.

P

As a legal historian, I have only studied pecia manuscripts of le-gal texts. These were often made in Bologna, for a long time the main center for the study of law and of legal book production, and my discussion will focus on production in northern Italy. In the course of my research I noticed that relatively few French legal manuscripts contain explicit pecia marks—very rarely do they contain a complete series, and in most manuscripts just a few. Italian manuscripts on the other hand very often record the

. Rouse, “The Book Trade,” –, “The Dissemination of Texts,” –, and Manuscripts and their Makers, :.

. Hardly anything is known about the book production at the University of Na-ples.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

full sequence of pecia marks, found throughout the manuscript. The probable reason for this difference is that in Italy, much more than in France, the pecia had a second function: it additionally served as a unit of account upon which the mutual obligations be-tween the scribe and his client were based.

In the Bolognese public registers, or Memoriali, an institution established in , an enormous number of records of copying contracts has been preserved, that is, contracts in which a copyist promises to write a text. So far, more than two hundred of them have been published. For no other university is there such an abundant resource that contributes to our knowledge of book production. It can be seen in these contracts that very often, and especially when the scribe had to write the Glossa ordinaria (one of the standard commentaries on both civil and canon law) the parties, instead of fixing a price for the whole work, had agreed on a payment per pecia. The pecia marks enabled the copyist to de-mand his wage, but also to show that he had fulfilled his monthly duty: many contracts contain a clause that obliges the scribe to copy a monthly minimum of four, five, or six pecias, sometimes more. Another more common clause does not concern the quan-tity but the quality of his work: he often pledges himself to write “in an equally good or better script” (de eque bona littera sive me-

. See Chartularium Studii Bononiensis: Documenti per la storia dell’università di Bologna dalle origini fino al secolo XV, vols. (Bologna, –), vols. , –, and –: these documents date from to and ; some twenty-five doc-uments, dating –, are published in Gianfranco Orlandelli, Il libro a Bo-logna dal al : Documenti con uno studio su il contratto di scrittura nella dottrina notarile bolognese (Bologna, ); fourteen examples (eight from Bolo-gna and six from Modena) are given in Frank Soetermeer, “A propos d’une famille de copistes: Quelques remarques sur la librairie à Bologne aux XIIIe et XIVe siè-cles,” Studi Medievali, ser. , (): – at –, reprinted in Frank Soeter-meer, Livres et juristes au Moyen Âge (Goldbach, ), –, see also: addenda et corrigenda, –. A few contracts from Avignon are found in P. Pansier, His-toire du livre et de l’imprimerie à Avignon du XIVme au XVIme siècle, vols. (Avignon, ; repr. Nieuwkoop, ), :esp. –. A contract from Orange is published in Françoise Gasparri, “Un contrat de copiste à Orange au XVe siècle,” Scriptorium (): –.

. Soetermeer (), –; Soetermeer (), –. The prices that the scribes stipulated are discussed in: Luciana Devoti, “Aspetti della produzione del libro a Bologna: Il prezzo di copia del manoscritto giuridico tra XIII e XIV secolo,” Scrittura e civiltà (): –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

liori) that he had used on a cedula (piece of parchment), which is described in the contract and which from then on had to serve as a standard. And finally the client often required the copyist to ex-ecute the work without interruption (scribere sine interposicione alicuius alterius operis), this to prevent him from simultaneously taking on other jobs for better-paying clients and, in consequence, jeopardizing the completion of his original contract.

Apparently this latter circumstance was a frequent problem, and was one of the reasons why copyists had a rather bad repu-tation on the market. By this period these copyists were always professionals (in Bologna often notaries), rather than students. Unlike in Paris, young men who studied law in Bologna or Padua usually came from well-to-do families. The student working his way through university by writing texts for others was conse-quently very rare, at least before the middle of the fourteenth cen-tury. Odofredo (d. ), a well-known professor of civil law who also owned a bookshop, did not hesitate to write about copyists that “all of them are thieves and swindlers” (omnes sunt latrones et baratatores). With this point of view—not uncommon in those days—it is not surprising that he ardently supported a Bolognese doctrine that had been formulated by his predecessors at the be-ginning of the thirteenth century and which implied that a copy-ist who was in default could be imprisoned. This indeed occurred from time to time. In Bologna the prison for defaulters had an unambiguous name: Malpaga (“Badpaying”). There, on rations of bread and water, the copyist had to complete his work. It goes without saying that if he took to his heels and made his way to an-other studium, taking along with him the quires he had already copied, the corrective measure was no use to the defrauded cli-ent. In any case, this course of action was adopted by a number of French lawyers, and in Spain the University of Lérida even in-

. Soetermeer, “A propos d’une famille,” –, –.. In Odofredus, Lectura super Digesto novo (Lyon, ; repr. Bologna, ), fol.

rb, in a commentary on D...... In “Guido f[ilius] q[uondam] Lançalotti custos carceris Malpaghe com-

munis Bon.” hands over several prisoners to another person. One of them is “Nich-olaus Anglie q. Roberti pro scriptura operatus (legendum: apparatus) Digesti Novi et pro viginti quinque lib[ris] et pro expensis, ad petitionem d[omini] Thomaxii de Osculea de Anglia.” See Orlandelli, , no. .

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

serted it in its statutes. When not the scribe but his contractor was found to be untrustworthy, reluctant to pay his debt, the for-mer also had recourse to a far less drastic legal remedy: among the medieval lawyers it was universally accepted that the scribe then had a lien on the quires he still had in his possession.

In northern Italy a contractual clause in which a copyist prom-ised to copy monthly a minimum number of pecias was less prone to misunderstanding, since there exemplars often had a fixed, standard division into pecias. Exemplars of the Glossa ordi-naria to the Digestum vetus, for example, almost always consisted of eighty-four pecias. This had the advantage that pecias of dif-ferent exemplars of this work were easily interchangeable; I will discuss the causes of this phenomenon further on. For the mo-ment it should be clear why pecia marks, and often complete se-ries of them, occur much more often in Italian manuscripts (to a great extent legal texts) than in French. Although Destrez must have noticed this, he failed to point out this rather important de-tail. Among manuscripts with more or less complete series of (ex-plicit) pecia marks, legal manuscripts seem indeed to be in the majority. Some sixty years after Destrez had published La Pecia, Father Louis Jacques Bataillon examined his notes to determine in what kind of texts he had found the most pecia manuscripts (that is, manuscripts with explicit pecia marks). The results are striking, and although the numbers have relatively limited value, they are interesting with regard to the proportion between legal and other pecia manuscripts. The texts for which Destrez found twenty or more pecia manuscripts are considerable: there were twenty-four, preserved in manuscripts. Only four texts (com-prising manuscripts) were works on theology (all by Thomas Aquinas); two belonged to the field of pastoral theology, and only one involved the liberal arts. There were no texts on med-icine. On the other hand no less than seventeen, or two thirds of the total, were legal works. To compare the importance of the

. See Frank Soetermeer, “La carcerazione del copista,” Rivista Internazionale di Diritto Comune (): –, reprinted in Soetermeer, Livres et juristes, –.

. Paola Maffei, “Note sulla tutela del copista nel diritto comune medievale,” in A Ennio Cortese, ed. Domenico Maffei and Italo Birocchi, vols. (Rome, ), :–.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

two studies of law: five texts were of civil, that is, secular law ( manuscripts), but these were greatly outnumbered by works on canon law: twelve (totaling manuscripts, or more than half of the total). The latter numbers confirm a view recently expressed by Gero Dolezalek, that “Roman law spread over medieval Europe as a concomitant of canon law” and that it “traveled as a lackey on the footboard of canon law’s carriage.” Although he claims this is “widely known,” this last seems to me rather doubtful, for to this day the crucial role of the Church in the process of the pen-etration of Roman law is often highly underestimated and mis-understood.

B ,

While the basic differences between French and Italian types of administration are of minor importance, in both countries the universities tried to control book production. In Bologna this began about half a century earlier than in Paris. Exemplars and exemplatores, an older term for the stationers, are already men-tioned in a document of , the so-called contract of Vercelli. Five years earlier a conflict had arisen between the Bolognese stu-dents and the Commune, and an exodus to Padua took place, where a new university thus came into being. But after a couple of years a large part of its students moved with their professors to Vercelli, a city which, very logically, regarded their presence with great interest. Among the privileges the students had demanded in exchange was that the city appoint stationers, who, according to the document, should keep on hand exemplars of the basic le-gal texts, as well as of the main commentaries on these texts—the apparatus of glosses. The second requirement was that these ex-emplars embody reliable texts: they had to be competentia et cor-

. Louis-Jacques Bataillon, “L’università,” in Lo spazio letterario del medioevo, pt. , Il medioevo latino, ed. Guglielmo Cavallo et al., vols. (Rome, –), :–, esp. –.

. See Gero Dolezalek, “Canon Law and Roman Law: Some Statistics on Manu-scripts in the Vatican Library,” in A Ennio Cortese, :–, esp. .

. For the text see Savigny, :– and Hastings Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, ed. F.M. Powicke and A.B. Emden, vols. (Oxford, ), :–.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

recta. And finally, the two rectors of the universitas scolarium (one being an Italian, his colleague an ultramontanus) reserved the right to fix rental prices in a so-called taxation table. This, in a nutshell, is without a doubt how the system already functioned in Padua and in Bologna as well.

In the Vercelli document are set forth the three main objec-tives of university control of book production. It aimed in the first place to guarantee that there would be enough exemplars available for masters and students who had commissioned a professional scribe to write a book for them. This was indeed the primary goal, very well illustrated by the following phrase in the act of appoint-ment of a stationer in Padua, dating from years later—cum absque exemplaribus universitas stare non possit—“since a univer-sity cannot survive without exemplars.” The contract also shows that the university tried to exercise supervision over the accuracy of the stationers’ exemplars, and finally endeavored to protect the members of the universitas scolarium against the raising of prices by the stationers and other forms of extortion.

In Italy, the control exerted by the rectors not only related to the rents to be paid to the stationers, but also specified for every text the number of pecias its exemplar should contain. This was an (unsuccessful) attempt to prevent stationers who composed a new exemplar from writing it in such a way that the new one com-prised more pecias than the old one, a practice explicitly forbid-den in the statutes of the University of Bologna. These statutes, published in , were a codification of earlier statutes, most of them unfortunately lost. They contained a taxation list in which were itemized all the legal texts for which pecias were available at the Bolognese bookshops. Although it is incomplete and con-tains many corruptions, the list is an important source for our knowledge of Bolognese book production. These statutes were first published at the end of the nineteenth century. Later on six

. Andrea Gloria, Monumenti della Università di Padova (–) (Venice, ; repr. Bologna, ), Appendix , –; Heinrich Denifle, Die Entstehung der Universitäten des Mittelalters (Berlin, ; repr. Graz, ), –.

. The original version () is lost, but a revised version () was published in Heinrich Denifle, “Die Statuten der Juristen-Universität Bologna vom J. –, und deren Verhältniss zu jenen Paduas, Perugias, Florenz,” Archiv für Litter-atur- und Kirchengeschichte des Mittelalters (; repr. Graz ): –; also in Carlo Malagola, ed., Statuti delle Università e dei Collegi dello Studio bolognese

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

inventories of the pecias available in the bookshops of individual Bolognese stationers were discovered. They all date from the sec-ond half of the thirteenth century, but unfortunately the statio-ners’ names are not specified.

As previously mentioned, the Bolognese university rectors were obliged to promote book production. In reality, however, they were hardly able to exert any influence on this process. To be admitted to the profession a stationer had only to pay a deposit of fifteen pounds, from which fines could be deducted. He also had to produce a person willing to be a guarantor. And finally, just as at most other universities, Bolognese stationers had to swear an oath to the rectors, promising to observe the statutes. Severe of-fences could be punished by the rectors with privatio, which in fact was a general boycott. This was probably very rare, however, and most stationers remained in office until their death.

Although they were supervised by the university, the Bolog-nese stationers were predominantly freelancers, just as their col-leagues were in Paris. They were unsalaried and their success was to a great degree dependent on the ups and downs of the uni-

(Bologna, , repr. Bologna, ). I published and analyzed an older version of the taxation list dating from in Soetermeer (), – and Soetermeer (), –.

. Five were published by Miroslav Boháček, “Zur Geschichte der Stationarii von Bologna,” in Eos. Commentarii Societas Philologae Polonorum (): –, Thomas Kaeppeli and Hugues V. Shooner, Les Manuscrits médiévaux de Saint-Dominique de Dubrovnik (Rome, ), Appendix II: Listes de taxation d’ouvrages de droit, –, especially onwards; and Jean-François Genest, “Le Fonds ju-ridique d’un stationnaire italien à la fin du XIIIe siècle: Matériaux nouveaux pour servir à l’histoire de la pecia,” in La Production du livre, –; for a sixth one pub-lished by myself, see Soetermeer (), –, –; Soetermeer (), –, –. The division into pecias of several works on both learned laws is also found in a document (probably Italian) from the end of the fourteenth century; see Giovanna Murano, “La lista di opere peciate nel manoscritto Leipzig, Univer-sitätsbibliothek, ,” Rivista Internazionale di Diritto Comune (): –.

. I have found some documents from the last decades of the thirteenth cen-tury that demonstrate that by that time this rule was indeed practiced: Soeter-meer (), ; Soetermeer (), . However, documents seem to be lacking for later periods.

. Exceptions are Master Anthonius Bonaventure, who went bankrupt (ca. ), and his colleague Gualterius Efficax anglicus, who had inflicted a fatal injury on

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

versity. During the thirteenth and the first half of the fourteenth century the Bolognese university underwent various periods of crisis, caused by secessions. One of the first has already been cited, occurring in , in which students and their professors went to Padua and founded a new university. At subsequent se-cessions students moved three times more to Padua (in , , and ), once to Siena (), and once to Pisa (). These se-cessions had different causes: once () due to the threat of a civil war (which indeed broke out); another time () resulting from a clash between the students and the City; and repeatedly, they were the consequence of conflicts between the City and the pope, which led to the imposition of a papal interdict (, , and ). In all cases, during these events not only students and professors left the city but other professionals as well, including the copyists who earned a living by writing texts for them, and the stationers who held the models needed by the copyists and their clients, and whose livelihood was threatened. Although a severe penalty was imposed in the City Statutes for taking exemplars along to other studia, the stationers ignored this prohibition. I have located several documents dealing with the illegal export of exemplars to Siena and Pisa during the secessions that took place in and , and there is no doubt that this situation had al-ready occurred during the thirteenth century.

In this way Bolognese exemplars ended up at other Italian uni-versities, where they were often duplicated. In his book on the pecia system Jean Destrez emphasized that the exemplars con-tained more or less “official” texts, approved by the university, and that for this reason at any given university there was always only one exemplar of a text. In Destrez’s opinion manuscripts that pre-sented pecia marks at the same places had always been copied from the same exemplar. Theologians who have prepared editions

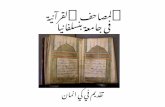

an illuminator (). Susan L’Engle discovered that the text of Vienna, Öster-reichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. (Liber Sextus with the Glossa ordinaria) was copied from the latter’s pecias. (fig. ) On these two stationers, see Soeter-meer (), , –, , and Soetermeer (), , –, , . For a detailed description of the pecia marks in Cod. , see Murano, Manoscritti prodotti, –, no. . In her opinion the stationer may have copied part of the manuscript himself.

. Soetermeer (), –; Soetermeer (), –.

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

Figure .

“per pecias Gualterii efficax”Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. , fol. v, full page and detail

Text of the Liber sextus copied from the pecias of Gualterius Efficax anglicus With permission of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek,,Vienna

See n.

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

of the works of Thomas Aquinas and other authors have estab-lished that the latter is certainly wrong. Parisian stationers often had duplicate or even triplicate pecias of important works, and as these series had identical divisions, the pecias were easily inter-changeable. In such cases it is unrealistic to believe that an editor can reconstruct the relationships among manuscripts and draw up a stemma codicum.

The same situation was true for Bologna. The inventory of the estate of the stationer Solimano (d. ) shows that he owned the pecias of the apparatus of glosses considered the Ordinary Gloss even in quadruplicate or quintuplicate. Moreover, in Bo-logna all stationers were obliged to have exemplars of this lat-ter type of text. This was also an advantage for the copyists and their clients. If a copyist went to the bookshop to exchange the pe-cia he had copied for the following one and noticed that the one he needed was not available, since it was at this moment being copied by someone else, he could rent it from another stationer and continue his work. On the other hand, this would affect the amount his client owed the stationer from whom the other pecias had been obtained. Consequently, the copyists sometimes men-tioned in their pecia marks the name of the stationer who owned the pecia they had just finished, i.e.: “finitur xii. pecia martini.” The pecia marks that survive in a Bolognese copy of the Diges-tum novum produced around – (Paris, Bibliothèque natio-nale de France, ms. lat. ) are an interesting illustration of this phenomenon. From these marks I was able to determine that in this manuscript, both for the text and for its surrounding gloss, the copyists used pecias belonging to no less than five different Bolognese stationers.

Another idea of Destrez’s was that the division into a set num-ber of pecias for an exemplar was always distinctive to each in-dividual university. He reasoned that if, for example, the Parisian exemplar of a work consisted of pecias, the one in Oxford would comprise , and the one in Padua , and in this way we should easily be able to determine the origin of a manuscript. In terms of Italian universities, however, this supposition was also in-

. First published in Lodovico Frati, “Gli Stazionarî bolognesi nel Medio Evo,”Archivio Storico Italiano, ser. , (): –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

correct. In Italy, exemplars often had a standard division that was the same in Bologna, Padua, Siena, and elsewhere. This means that the number of pecias of the exemplar from which the text has been copied is not in itself proof of a manuscript’s origin.

Upon the publication of the medieval statutes of many uni-versities at the end of the nineteenth century, their accessibility awakened interest in the book production at these universities, since these texts frequently contain provisions for the stationers or beadles who dealt in pecias. Often these rules prescribe that the text of their exemplars be accurate. In Bologna there was in fact a committee, composed of six students, which supervised the stationers and book production. One of the tasks of these pecia-rii, as they were called, was to control the correctness of the pe-cias. In actuality, however, their control could not have been very effective, since thousands of pecias circulated in Bologna. Most likely they only checked that a pecia bore the note “cor[recta]” at its end, without certifying that the correction had been accurate. I surmise that in practice the peciarii mainly acted as a complaint committee. Many copyists must have been well aware that the pe-cias they copied were somewhat corrupt. Some of them alluded to this in the pecia marks they wrote in the margins, in order to ac-quit themselves with their clients: “fi<nitur> iiia., pessima pet<ia> fuit;” or “hic fi<nitur> xvii. pe<cia> et fuit falsa” (or “ualde falsa,” “multum corrupta,” “corrupta et falsa,” or “falsa falsissima”). Many other universities and law schools undoubtedly lacked any control whatsoever. According to a phrase in the statutes of the University of Perugia (), the function of peciarius had not ex-isted there “since time immemorial” (“memoria hominum”).

C

The appearance of Bolognese manuscripts is very often splendid, but the quality of the text in many cases is mediocre. According

. Soetermeer (), –; Soetermeer (), –.. Such notes occur for example in Cesena, Biblioteca Malatestiana, Cod. S.II.;

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Cod. Vat. lat. ; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. lat. , which are all Bolognese. See Soetermeer (), –; Soetermeer (), –.

. Soetermeer (), ; Soetermeer (), .

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

to the late Gianfranco Orlandelli, this derives from the fact that most of the copyists who worked in Bologna had come from else-where and had therefore failed to acquire the necessary qualifi-cation and specialization in their trade. He contended that the influence of this circumstance on the tradition of the scholarly texts “should not be underestimated.” I myself have some doubts about his premises, which were adopted by various others who have written on Bolognese book production. It is true that many copyists came from other cities or from villages in the surround-ing districts, but considerably fewer than Orlandelli thought. While he encountered very few copyists called “bononiensis” in the Bolognese notarial deeds for which an extract was copied in the public registers (and published in the Chartularium), he did not realize that the Bolognese notaries usually mentioned the or-igin of a person only if he was not a Bolognese citizen and was as a result (in the Middle Ages) subject to the law of his place of ori-gin. A study of the Bolognese copying contracts shows that many a copyist who came from another place was generally considered an expert and therefore succeeded in stipulating a price for his work far above the average. In my opinion, the poor quality of the text in so many university-produced manuscripts derives from the corruptness of the pecias utilized by the copyists.

It would therefore seem that the pecia system was not a strict guarantee of quality control, but, more accurately, an optimum procedure for book production. Destrez and others rather naively thought that the stationers’ exemplars contained the texts as ap-proved by the university authorities (who would have acted as censors in this respect), and that they were thus invariably trust-worthy—but experience has shown that even theological univer-sity manuscripts quite often contain a fairly corrupt text. Destrez

. Orlandelli, –, .. See Frank Soetermeer, “Exemplar und Pecia: Zur Herstellung juristischer

Bücher in Bologna im . und . Jahrhundert,” in Juristische Buchproduktion, –, esp. –. I am very grateful to Dr. Elena Kazbekova of the Department of Medieval History, Institute of General History, Russian Academy of Sciences, who has kindly translated this essay for me into Russian. It will be published in Sred-nije veka (), under the title “Exemplar i Pecia: Proizvodstvo juridicheskich rukopisej v Bolonje v XIII-XIV vekach.”

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

also believed that the existence of the pecia system would simplify the critical editing of a text, although nowadays this produc-tion technique has proved instead to complicate the editor’s work, since quite often these unreliable university-produced manu-scripts are the only surviving copies of a given text.

Outside critical editions, however, an acquaintance with the pecia system can be useful to scholars in their assessment of the exact nature of a given manuscript, and may help resolve ques-tions of dating and provenance. Familiarity with the pecia system can also help to clarify the evolution of important and influential medieval texts. Among these, in first place are the apparatus of glosses considered the Glossa ordinaria. For more than three cen-turies they were studied in the classroom at all universities where both learned laws were taught. All of them were compiled by ju-rists who taught at the University of Bologna during the thir-teenth and fourteenth centuries. After a stationer had published a first version, the author often completed the text with numerous additions, which are not present in older manuscripts. The statio-ner wrote these new comments in the margins of the pecias, so that the copyist of the gloss could integrate them into the stan-dard text. Often these additions were rather late in penetrating the universities and law schools in France, where meanwhile the text had often undergone an independent development. Contrary

. This was already severely criticized by Étienne Axters, “La Critique textuelle médiévale doit-elle être désormais établie en fonction de la «pecia»? Une réponse à Monsieur l’Abbé Destrez,” Angelicum (): –. See also Clemens S. Suer-mondt, “De textu Summae contra gentiles: Observationes aliquae ad recensorem quamdam,” Angelicum (): –, –; (): –. Nevertheless, Destrez’s idea that the texts had to be approved by the university authorities was by and large adopted without question by others. See for example Jacques le Goff, Les Intellectuels au Moyen Age (Paris, ), –; Jacques Verger, Les Universités au Moyen Age (Paris, ), –.

. See for example the introductions to the Editio Leonina of the works of Thomas Aquinas, and Antoine Dondaine, “L’Édition des oeuvres de saint Thomas,” Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie (): –; Raymond Macken, “Un ap-port important à l’ecdotique des manuscrits à pièces: A propos de l’édition léonine du commentaire de Thomas d’Aquin sur la Politique d’Aristote et de sa Tabula Li-bri Ethicorum,” Scriptorium (): –, and “L’Édition critique des ouvrages divulgués au moyen-âge au moyen d’un exemplar universitaire,” in La Production du livre, –; Louis-Jacques Bataillon, “Problèmes posés par l’édition critique des textes latins médiévaux,” Revue philosophique de Louvain (): –.

Frank Soetermeer

Pecia Manuscripts of Legal Texts

to their Italian colleagues, the French stationers not only wrote the additions of the author himself in the margins of the pecias, but also anonymous complementary texts by local professors. In this way these commentaries remained a living text, and mutually divergent textual traditions came into being.

Utrecht

. See Frank Soetermeer, “Due tradizioni testuali francesi dell‘Apparatus Digesti Novi di Accursio,” Rivista Internazionale di Diritto Comune (): –; re-printed in Soetermeer, Livres et juristes, –.