Bertha - Jazz Inside Magazine

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Bertha - Jazz Inside Magazine

HOPEHOPE

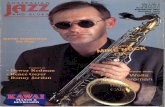

Eric Nemeyer’s

WWW.JAZZINSIDEMAGAZINE.COMWWW.JAZZINSIDEMAGAZINE.COM October 2021October 2021

I call myself a survivorI call myself a survivor

Interviews

Barry HarrisBarry Harris

Benny MaupinBenny Maupin

Michael PedicinMichael Pedicin

Comprehensive Comprehensive

Directory Directory of NY ClubS, ConcertS of NY ClubS, ConcertS

BerthaBertha

December 2015 � Jazz Inside Magazine � www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

1 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

COVER-2-JI-15-12.pub page 1

Cyan

Magenta

Yellow

Black

Cyan

Magenta

Yellow

Black

Wednesday, December 09, 2015 15:43

1 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

ORDER THIS 200+ Page Book + CD - Only $19.95

2 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

Eric Nemeyer’s

CONTENTSCONTENTS

CLUBS, CONCERTS, EVENTSCLUBS, CONCERTS, EVENTS 3 Calendar of Events 10 Clubs & Venue Listings

12 Bertha Hope—I call myself a survivor 50 Vision Festival 2021—Photo Essay by

Ken Weiss

INTERVIEWSINTERVIEWS 28 Benny Maupin 35 Michael Pedicin 39 Barry Harris

Visit these websites: Jazz.org JJBabbitt.com MaxwellDrums.com

LIKE US www.facebook.com/

JazzInsideMedia

FOLLOW US www.twitter.com/

JazzInsideMag

WATCH US www.youtube.com/

JazzInsideMedia

Get Hundreds Of Media Placements — ONLINE — Major Network Media & Authority Sites & OFFLINE — Distribution To 1000’s of Print & Broadcast

Networks To Promote Your Music, Products & Performances In As Little As 24 Hours To Generate Traffic, Sales & Expanded Media Coverage!

PAY ONLY FOR RESULTS

PUBLICITY!

www.PressToRelease.com | MusicPressReleaseDistribution.com | 215-887-8880

Jazz Inside Magazine

ISSN: 2150-3419 (print) • ISSN 2150-3427 (online)

October 2021 – Volume 11, Number 1

Cover Photo and photo at right of Bertha Hope by Ken Weiss

Publisher: Eric Nemeyer Editor: Wendi Li Marketing Director: Cheryl Powers Advertising Sales & Marketing: Eric Nemeyer Circulation: Susan Brodsky Photo Editor: Joe Patitucci Layout and Design: Gail Gentry Contributors: Eric Nemeyer, Ken Weiss, Joe Patitucci.

ADVERTISING SALES 215-887-8880

Eric Nemeyer – [email protected]

ADVERTISING in Jazz Inside™ Magazine (print and online) Jazz Inside™ Magazine provides its advertisers with a unique opportunity to reach a highly specialized and committed jazz readership. Call our Advertising Sales Depart-ment at 215-887-8880 for media kit, rates and information.

Jazz Inside™ Magazine | Enthusiasm Corporation P.O. Box 8811, Elkins Park, PA 19027

Telephone: 215-887-8880 Email: [email protected]

Website: www.jazzinsidemagazine.com

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION Jazz Inside™ (published monthly). To order a subscription, call 215-887-8880 or visit Jazz Inside on the Internet at www.jazzinsidemagazine.com. Subscription rate is $49.95 per year, USA. Please allow up to 8 weeks for processing subscriptions & changes of address.

EDITORIAL POLICIES

Jazz Inside does not accept unsolicited manuscripts. Persons wishing to submit a manuscript or transcription are asked to request specific permission from Jazz Inside prior to submission. All materials sent become the property of Jazz Inside unless otherwise agreed to in writing. Opinions expressed in Jazz Inside by contrib-uting writers are their own and do not necessarily express the opinions of Jazz Inside, Eric Nemeyer Corporation or its affiliates.

SUBMITTING PRODUCTS FOR REVIEW Companies or individuals seeking reviews of their recordings, books, videos, software and other products: Send TWO COPIES of each CD or product to the attention of the Editorial Dept. All materials sent become the property of Jazz Inside, and may or may not be reviewed, at any time.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

Copyright © 2009-2021 by Enthusiasm Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or duplicated in any form, by any means without prior written consent. Copying of this publication is in violation of the United States Federal Copyright Law (17 USC 101 et seq.). Violators may be subject to criminal penalties and liability for substantial monetary damages, including statutory damages up to $50,000 per infringement, costs and attorneys fees.

3 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

BIRDLAND JAZZ CLUB 315 West 44th St, New York, NY 10036

212-581-3080

Friday Oct 1: Birdland Big Band; Stacey

Kent and Art Hirahara “Songs from Other

Places” Album Release; Natalie Douglas

Saturday Oct 2: Eric Comstock with Sean

Smith (Bass) & special guest Barbara Fasa-

no (Voice); Stacey Kent and Art Hirahara

“Songs from Other Places” Album Release;

Natalie Douglas

Sunday Oct 3: Scott Reeves Jazz Orches-

tra: Featuring Vocalist Carolyn Leonhart;

Arturo O’Farrill and Afro Latin Jazz En-

semble; Marissa Mulder: Souvenirs, A Trib-

ute to the Songs of John Prine

Monday Oct 4: Amanda Green & Friends

Vaxxed AF!; Susan Mack “Music In The

Air”; Jim Caruso’s Cast Party

Tuesday Oct 5: Ron Carter’s Golden Strik-

er Trio with Russell Malone and Donald

Vega; The Lineup with Susie Mosher; Ron

Carter’s Golden Striker Trio with Russell

Malone and Donald Vega

Wednesday Oct 6: David Ostwald’s Louis

Armstrong Eternity Band; Ron Carter’s

Golden Striker Trio with Russell Malone

and Donald Vega; Dan Block Quartet

Thursday Oct 7: Ron Carter’s Golden

Striker Trio with Russell Malone and Don-

ald Vega

Friday Oct 8: Birdland Big Band; Ron

Carter’s Golden Striker Trio with Russell

Malone and Donald Vega; Don Braden

Quartet

Saturday Oct 9: Eric Comstock with Sean

Smith (Bass) & special guest Barbara Fasa-

no (Voice); Ron Carter’s Golden Striker

Trio with Russell Malone and Donald Vega;

Don Braden Quartet

Sunday Oct 10: Marcello Pellitteri; Arturo

O’Farrill and Afro Latin Jazz Ensemble;

Ann Kittredge: Movie Night with Alex

Rybeck and Sean Harkness

Monday Oct 11: Chad LB Quartet; Jim

Caruso’s Cast Party

Tuesday Oct 12: John Pizzarelli Trio; Tuck

& Patti Birdland Debut; Lineup with Susie

Mosher

Wednesday Oct 13: David Ostwald’s Louis

Armstrong Eternity Band; Tuck & Patti

Birdland Debut; John Pizzarelli Trio

Thursday Oct 14: Tuck & Patti; John Piz-

zarelli Trio;

Friday Oct 15: Birdland Big Band; John

(Continued on page 4)

CALENDAR OF EVENTSCALENDAR OF EVENTS

How to Get Your Gigs and Events Listed in Jazz Inside Magazine Submit your listings via e-mail to [email protected]. Include date, times, location, phone,

tickets/reservations. Deadline: 15th of the month preceding publication (October 15 for November) (We cannot guarantee the publication of all calendar submissions.)

ADVERTISING: Reserve your ads to promote your events and get the marketing advantage of con-trolling your own message — size, content, image, identity, photos and more. Contact the advertising department:

215-887-8880 | [email protected]

4 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

Pizzarelli Trio; Tuck & Patti Friday

Saturday Oct 16: Eric Comstock with Sean

Smith (Bass) & special guest Barbara Fasa-

no (Voice); John Pizzarelli Trio; Tuck &

Patti

Saturday Oct 16:

Sunday Oct 17: Jared Schonig Big Band

Album Release; Arturo O’Farrill and Afro

Latin Jazz Ensemble

Monday Oct 18: Dominick Farinacci Quar-

tet; Jim Caruso’s Cast Party

Tuesday Oct 19: Issac Delgado y La Nove-

na

Wednesday Oct 20: David Ostwald’s Louis

Armstrong Eternity Band; Issac Delgado y

La Novena

Thursday Oct 21: Issac Delgado y La No-

vena

Friday Oct 22: Birdland Big Band; Issac

Delgado y La Novena;

Saturday Oct 23: Eric Comstock with Sean

Smith (Bass) & special guest Barbara Fasa-

no (Voice); Issac Delgado y La Novena;

Steve Ross

Sunday Oct 24: Jennifer Wharton’s

Bonegasm; Arturo O’Farrill and Afro Latin

Jazz Ensemble; Benny Benack III Quartet

Monday Oct 25: Karen Oberlin Bewitched:

The Life and Lyrics of Lorenz Hart; Sasha

Dobson

Tuesday Oct 26: Django Reinhardt Festival

Wednesday Oct 27: David Ostwald’s Louis

Armstrong Eternity Band; Django Reinhardt

Festival; Larry Fuller Trio

Thursday Oct 28: Django Reinhardt Festi-

val; Anaïs Reno CD Release with Emmet

Cohen Trio; Django Reinhardt Festival

Friday Oct 29: Birdland Big Band; Django

Reinhardt Festival

Saturday Oct 30: Eric Comstock, Sean

Smith (Bass), Barbara Fasano (Voice);

Django Reinhardt Festival; Janis Siegel &

John DiMartino

Sunday Oct 31: Migiwa Miyajima and the

Miggy Augmented Orchestra; Arturo O’Far-

rill and Afro Latin Jazz Ensemble; Moipei

Triplets Embrace New York

BLUE NOTE 131 W. 3rd St, New York, NY

BlueNote.net

Friday Oct 1: Robert Glasper Original

Acoustic Trio

Saturday Oct 2: Robert Glasper Original

Acoustic Trio

Sunday Oct 3: Robert Glasper Original

Acoustic Trio

Monday Oct 4:

Tuesday Oct 5: Robert Glasper X Ledisi

Wednesday Oct 6: Robert Glasper X Ledisi

Thursday Oct 7: To Be Announced

Friday Oct 8: To Be Announced

Saturday Oct 9: To Be Announced

Sunday Oct 10: To Be Announced

Monday Oct 11:

Tuesday Oct 12: Tribute To Wayne Shorter

(Featuring Marcus Strickland, Kendrick

Scott, Keyon Harrold, Vicente Archer)

Wednesday Oct 13: Tribute To Wayne

Shorter (Featuring Marcus Strickland,

Kendrick Scott, Keyon Harrold, Vicente

Archer)

Thursday Oct 14: Robert Glasper X Me-

shell Ndegeocello

Friday Oct 15: Robert Glasper X Meshell

Ndegeocello

Saturday Oct 16: Robert Glasper X Me-

shell Ndegeocello

Sunday Oct 17: Robert Glasper X Meshell

Ndegeocello

Monday Oct 18:

Tuesday Oct 19: Robert Glasper & Terrace

Martin Presents Dinner Party

Wednesday Oct 20: Robert Glasper & Ter-

race Martin Presents Dinner Party

Thursday Oct 21: Robert Glasper & Ter-

race Martin Presents Dinner Party

Friday Oct 22: Robert Glasper & Terrace

Martin Presents Dinner Party

Saturday Oct 23: Robert Glasper & Ter-

race Martin Presents Dinner Party

Sunday Oct 24: Robert Glasper & Terrace

Martin Presents Dinner Party

Monday Oct 25:

Tuesday Oct 26: Robert Glasper - Black

Radio With Special Guests PJ Morton &

Bilal

Wednesday Oct 27: Robert Glasper - Black

Radio With Special Guests PJ Morton &

Bilal

Thursday Oct 28: Robert Glasper - Black

Radio With Special Guests PJ Morton &

Bilal

Friday Oct 29: Robert Glasper - Black Ra-

dio With Special Guests PJ Morton & Bilal

Saturday Oct 30: Robert Glasper - Black

Radio With Special Guests PJ Morton &

Bilal

Sunday Oct 31: Robert Glasper - Black

Radio With Special Guests PJ Morton &

Bilal

(Continued on page 5)

Jazz

Mu

sic

De

als

.co

m

Jazz

Lo

vers

’ Li

feti

me

Co

lle

cti

on

Jazz

Mu

sic

De

als

.co

m

5 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

DIZZY'S CLUB Broadway at 60th Street, 5th floor, Time

Warner Center, New York City, NY 10019 212-258-9595

Friday Oct 1: Joey Alexander Trio

Saturday Oct 2: Joey Alexander Trio

Sunday Oct 3: Joey Alexander Trio

Monday Oct 4:

Tuesday Oct 5:

Wednesday Oct 6:

Thursday Oct 7: Joey Defrancesco Album

Release Celebration

Friday Oct 8: Joey Defrancesco Album

Release Celebration

Saturday Oct 9: Joey Defrancesco Album

Release Celebration

Sunday Oct 10: Joey Defrancesco Album

Release Celebration

Monday Oct 11:

Tuesday Oct 12:

Wednesday Oct 13:

Thursday Oct 14: Edmar Castaneda Album

Release Concert: Family

Friday Oct 15: Mike Ledonne Trio With

Ron Carter And Joe Farnsworth

Saturday Oct 16: Mike Ledonne Trio With

Ron Carter And Joe Farnsworth

Sunday Oct 17: Samara Joy Ft. Pasquale

Grasso Trio

Monday Oct 18:

Tuesday Oct 19:

Wednesday Oct 20:

Thursday Oct 21: Christian Sands

Friday Oct 22: Christian Sands

Saturday Oct 23: Christian Sands

Sunday Oct 24: Ashley Pezzotti And Her

Trio

Monday Oct 25:

Tuesday Oct 26:

Wednesday Oct 27:

Thursday Oct 28: Jeremy Pelt Quintet

Friday Oct 29: Jeremy Pelt Quintet

Saturday Sunday Oct 30: Jeremy Pelt Quin-

tet

Sunday Oct 31:

Monday Nov 1: The Trio Featuring Ted

Nash, Steve Cardenas, Ben Allison

Tuesday Nov 2: The Trio Featuring Ted

Nash, Steve Cardenas, Ben Allison

Wednesday Nov 3: The Trio Featuring Ted

Nash, Steve Cardenas, Ben Allison

Thursday Nov 4: Stéphane Wrembel’s

“Django New Orleans” w/ Guests Bria

Skonberg, Daisy Castro

Friday Nov 5: Stéphane Wrembel’s

“Django New Orleans” w/ Guests Bria

Skonberg, Daisy Castro

Nov 6: Stéphane Wrembel’s “Django New

Orleans” w/ Guests Bria Skonberg, Daisy

Castro

Nov 7: Stéphane Wrembel’s “Django New

Orleans” w/ Guests Bria Skonberg, Daisy

Castro

SMALLSLIVE JAZZ CLUB 183 West 10th Street-basement; NYC

Friday Oct 1: Doug Wamble Quartet; Phil-

ip Harper Quintet; Adam Birnbaum Quartet

Saturday Oct 2:

Sunday Oct 03: Alex Norris Quintet

Monday Oct 04: Ari Hoenig Quartet; Miki

Yamanaka Quartet & Jam Session

Tuesday Oct 05: Jason Brown Quartet;

David Gibson Quartet & Jam Session

Wednesday Oct 06: Troy Roberts Quartet;

Benny Benack Quintet & Jam Session

Thursday Oct 07: Sarah Hanahan Quartet;

Greg Glassman Quartet & Jam Session

(Continued on Page 8)

(Continued on page 8)

6 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

Brian Lynch Smalls Live Jazz Club, October 23, 2021 Photo © Eric Nemeyer

7 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

Dizzy’s Club, Jazz At Lincoln CenterDizzy’s Club, Jazz At Lincoln Center

November 1November 1--3, 20213, 2021

8 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

(Continued from Page 5)

Friday Oct 08: Mark Sherman Quartet;

Corey Wallace Dubtet & Jam Session

Saturday Oct 09: Wayne Escoffery Quar-

tet; Eric Wyatt Quartet & Jam Session

Sunday Oct 10: Mike Troy Quartet; Stefa-

no Doglioni Quintet & Jam Session

Monday Oct 11: Joe Farnsworth Quartet;

Jonathan Michel Quintet & Jam Session

Tuesday Oct 12: Mark Whitfield Trio;

Evan Sherman Quartet & Jam Session

Wednesday Oct 13: Pratt-Eckroth Band;

Benny Benack Quintet & Jam Session

Thursday Oct 14: Mike Clark / Michael

Zilber Quartet; Carlos Abadie Quintet &

Jam Session

Friday Oct 15: Dave Stryker Trio; Jon

Beshay Quartet & Jam Session

Saturday Oct 16: Palladium Plays The Mu-

sic Of Wayne Shorter; Stacy Dillard Quartet

& Jam Session

Sunday Oct 17: Joris Teepe Trio; Aaron

Johnson Quintet & Jam Session

Monday Oct 18: Eric Alexander Quartet;

Miki Yamanaka Trio & Jam Session

Tuesday Oct 19: Steve Nelson Quartet;

David Gibson Quartet & Jam Session

Wednesday Oct 20: Will Bernard Trio;

Benny Benack Quintet & Jam Session

Thursday Oct 21: David Gilmore Quintet;

Carlos Abadie Quintet & Jam Session

Saturday Oct 22: Brandon Lee Quintet;

Philip Harper Quintet & Jam Session

Saturday Oct 23: Brian Lynch Quintet;

Eric Wyatt Quartet & Jam Session

Sunday Oct 24: Richie Vitale Quartet Feat.

Frank Basile; Stefano Doglioni Quintet &

Jam

VILLAGE VANGUARD 178 7th Avenue South, New York, NY

212-255-4037

Friday Oct 1: Bill Charlap, piano; Peter

Washington, bass; Kenny Washington

Saturday Oct 2: Bill Charlap, piano; Peter

Washington, bass; Kenny Washington

Sunday Oct 3: Bill Charlap, piano; Peter

Washington, bass; Kenny Washington

Monday Oct 4: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra -

Saxophones Dick Oatts (lead alto) Billy

Drewes (alto) Rich Perry (tenor) Ralph

Lalama (tenor) Gary Smulyan (bari); Trum-

pets Nick Marchione (lead trumpet) John

Chudoba, Terell Stafford, Scott Wendholt;

Trombones Marshall Gilkes (lead trombone)

Jason Jackson, Dion Tucker, Douglas Purvi-

ance (bass trombone); Rhythm Section: Ad-

am Birnbaum (piano) David Wong (bass)

John Riley (drums)

Tuesday Oct 5: Eric Harland Voyager -

Eric Harland, drums; Harish Raghavan,

bass; Taylor Eigsti, piano; Walter Smith lll,

sax; Gilad Hekselman, guitar

Wednesday Oct 6: Eric Harland Voyager

Thursday Oct 7: Eric Harland Voyager

Friday Oct 8: Eric Harland Voyager

Saturday Oct 9: Eric Harland Voyager

Sunday Oct 10: Eric Harland Voyager

Monday Oct 11: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra

Tuesday Oct 12: Ambrose Akinmusire

Quintet - Ambrose Akinmusire, trumpet;

Walter Smith III, tenor sax; Micah Thomas,

piano; Matt Brewer, bass; Marcus Gilmore,

drums

Wednesday Oct 13: Ambrose Akinmusire

Thursday Oct 14: Ambrose Akinmusire

Friday Oct 15: Ambrose Akinmusire

Saturday Oct 16: Ambrose Akinmusire

Quintet

Sunday Oct 17: Ambrose Akinmusire

Quintet; MATINEE: John Zorn's New Ma-

sada Quartet

Monday Oct 18: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra

Tuesday Oct 19: Fred Hersch Duo With

Julian Lage

Wednesday Oct 20: Fred Hersch Duo With

Julian Lage

Thursday Oct 21: Fred Hersch Duo With

Julian Lage

Friday Oct 22: Fred Hersch Duo With Jul-

ian Lage

Saturday Oct 23: Fred Hersch Duo With

Julian Lage

Sunday Oct 24: Fred Hersch, Julian Lage;

MATINEE: John Zorn's New Masada Qt

Monday Oct 25: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra

Tuesday Oct 26: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

Wednesday Oct 27: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

Thursday Oct 28: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

Friday Oct 29: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

Saturday Oct 30: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

Sunday Oct 31: Ravi Coltrane Quartet

“...among human beings jealousy ranks distinctly as a

weakness; a trademark of small minds; a property of all small minds, yet a property

which even the smallest is ashamed of; and when accused of its possession will

lyingly deny it and resent the accusation as an insult.”

-Mark Twain

“Some people’s idea of free speech is that they are free

to say what they like, but if anyone says anything back that

is an outrage.”

- Winston Churchill

Jazz

Mu

sic

De

als

.co

m

Jazz

Lo

vers

’ Li

feti

me

Co

lle

cti

on

Jazz

Mu

sic

De

als

.co

m

“The obedient always think of themselves as virtuous rather than cowardly.”

- Robert Anton Wilson

9 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

Dizzy’s Club, Jazz At Lincoln CenterDizzy’s Club, Jazz At Lincoln Center

October 7October 7--10, 202110, 2021

10 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

5 C Cultural Center, 68 Avenue C. 212-477-5993.

www.5ccc.com

55 Bar, 55 Christopher St. 212-929-9883, 55bar.com

92nd St Y, 1395 Lexington Ave, New York, NY 10128,

212.415.5500, 92ndsty.org

Aaron Davis Hall, City College of NY, Convent Ave., 212-650-

6900, aarondavishall.org

Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center, Broadway & 65th St., 212-875

-5050, lincolncenter.org/default.asp

Allen Room, Lincoln Center, Time Warner Center, Broadway

and 60th, 5th floor, 212-258-9800, lincolncenter.org

American Museum of Natural History, 81st St. & Central Park

W., 212-769-5100, amnh.org

Antibes Bistro, 112 Suffolk Street. 212-533-6088. www.antibesbistro.com Arthur’s Tavern, 57 Grove St., 212-675-6879 or 917-301-8759,

arthurstavernnyc.com

Arts Maplewood, P.O. Box 383, Maplewood, NJ 07040; 973-

378-2133, artsmaplewood.org

Avery Fischer Hall, Lincoln Center, Columbus Ave. & 65th St.,

212-875-5030, lincolncenter.org

BAM Café, 30 Lafayette Av, Brooklyn, 718-636-4100, bam.org

Bar Chord, 1008 Cortelyou Rd., Brooklyn, barchordnyc.com

Bar Lunatico, 486 Halsey St., Brooklyn. 718-513-0339.

222.barlunatico.com

Barbes, 376 9th St. (corner of 6th Ave.), Park Slope, Brooklyn,

718-965-9177, barbesbrooklyn.com

Barge Music, Fulton Ferry Landing, Brooklyn, 718-624-2083,

bargemusic.org

B.B. King’s Blues Bar, 237 W. 42nd St., 212-997-4144,

bbkingblues.com

Beacon Theatre, 74th St. & Broadway, 212-496-7070

Beco Bar, 45 Richardson, Brooklyn. 718-599-1645.

www.becobar.com

Bickford Theatre, on Columbia Turnpike @ Normandy Heights

Road, east of downtown Morristown. 973-744-2600

Birdland, 315 W. 44th, 212-581-3080

Blue Note, 131 W. 3rd, 212-475-8592, bluenotejazz.com

Bourbon St Bar and Grille, 346 W. 46th St, NY, 10036,

212-245-2030, [email protected]

Bowery Poetry Club, 308 Bowery (at Bleecker), 212-614-0505,

bowerypoetry.com

BRIC House, 647 Fulton St. Brooklyn, NY 11217, 718-683-

5600, http://bricartsmedia.org

Brooklyn Public Library, Grand Army Plaza, 2nd Fl, Brooklyn,

NY, 718-230-2100, brooklynpubliclibrary.org

Café Carlyle, 35 E. 76th St., 212-570-7189, thecarlyle.com

Café Loup, 105 W. 13th St. (West Village) , between Sixth and

Seventh Aves., 212-255-4746

Café St. Bart’s, 109 E. 50th St, 212-888-2664, cafestbarts.com

Cafe Noctambulo, 178 2nd Ave. 212-995-0900. cafenoctam-

bulo.com

Caffe Vivaldi, 32 Jones St, NYC; caffevivaldi.com

Candlelight Lounge, 24 Passaic St, Trenton. 609-695-9612.

Carnegie Hall, 7th Av & 57th, 212-247-7800, carnegiehall.org

Cassandra’s Jazz, 2256 7th Avenue. 917-435-2250. cassan-

drasjazz.com

Chico’s House Of Jazz, In Shoppes at the Arcade, 631 Lake

Ave., Asbury Park, 732-774-5299

City Winery, 155 Varick St. Bet. Vandam & Spring St., 212-608

-0555. citywinery.com

Cleopatra’s Needle, 2485 Broadway (betw 92nd & 93rd), 212-

769-6969, cleopatrasneedleny.com

Club Bonafide, 212 W. 52nd, 646-918-6189. clubbonafide.com

C’mon Everybody, 325 Franklin Avenue, Brooklyn.

www.cmoneverybody.com

Copeland’s, 547 W. 145th St. (at Bdwy), 212-234-2356

Cornelia St Café, 29 Cornelia, 212-989-9319

Count Basie Theatre, 99 Monmouth St., Red Bank, New Jersey

07701, 732-842-9000, countbasietheatre.org

Crossroads at Garwood, 78 North Ave., Garwood, NJ 07027,

908-232-5666

Cutting Room, 19 W. 24th St, 212-691-1900

Dizzy’s Club, Broadway at 60th St., 5th Floor, 212-258-9595,

jalc.com

DROM, 85 Avenue A, New York, 212-777-1157, dromnyc.com

The Ear Inn, 326 Spring St., NY, 212-226-9060, earinn.com

East Village Social, 126 St. Marks Place. 646-755-8662.

www.evsnyc.com

Edward Hopper House, 82 N. Broadway, Nyack NY. 854-358-

0774.

El Museo Del Barrio, 1230 Fifth Ave (at 104th St.), Tel: 212-

831-7272, Fax: 212-831-7927, elmuseo.org

Esperanto, 145 Avenue C. 212-505-6559.

www.esperantony.com

The Falcon, 1348 Rt. 9W, Marlboro, NY., 845) 236-7970,

Fat Cat, 75 Christopher St., 212-675-7369, fatcatjazz.com

Fine and Rare, 9 East 37th Street. www.fineandrare.nyc

Five Spot, 459 Myrtle Ave, Brooklyn, NY, 718-852-0202,

fivespotsoulfood.com

Flushing Town Hall, 137-35 Northern Blvd., Flushing, NY, 718

-463-7700 x222, flushingtownhall.org

For My Sweet, 1103 Fulton St., Brooklyn, NY 718-857-1427

Galapagos, 70 N. 6th St., Brooklyn, NY, 718-782-5188, galapa-

gosartspace.com

Garage Restaurant and Café, 99 Seventh Ave. (betw 4th and

Bleecker), 212-645-0600, garagerest.com

Garden Café, 4961 Broadway, by 207th St., New York, 10034,

212-544-9480

Gin Fizz, 308 Lenox Ave, 2nd floor. (212) 289-2220.

www.ginfizzharlem.com

Ginny’s Supper Club, 310 Malcolm X Boulevard Manhattan,

NY 10027, 212-792-9001, http://redroosterharlem.com/ginnys/

Glen Rock Inn, 222 Rock Road, Glen Rock, NJ, (201) 445-

2362, glenrockinn.com

GoodRoom, 98 Meserole, Bklyn, 718-349-2373, good-roombk.com. Green Growler, 368 S, Riverside Ave., Croton-on-Hudson NY.

914-862-0961. www.thegreengrowler.com

Greenwich Village Bistro, 13 Carmine St., 212-206-9777,

greenwichvillagebistro.com

Harlem on 5th, 2150 5th Avenue. 212-234-5600.

www.harlemonfifth.com

Harlem Tea Room, 1793A Madison Ave., 212-348-3471,

harlemtearoom.com

Hat City Kitchen, 459 Valley St, Orange. 862-252-9147.

hatcitykitchen.com

Havana Central West End, 2911 Broadway/114th St), NYC,

212-662-8830, havanacentral.com

Highline Ballroom, 431 West 16th St (between 9th & 10th Ave.

highlineballroom.com, 212-414-4314.

Hopewell Valley Bistro, 15 East Broad St, Hopewell, NJ 08525,

609-466-9889, hopewellvalleybistro.com

Hudson Room, 27 S. Division St., Peekskill NY. 914-788-FOOD. hudsonroom.com Hyatt New Brunswick, 2 Albany St., New Brunswick, NJ

IBeam Music Studio, 168 7th St., Brooklyn, ibeambrook-

lyn.com

INC American Bar & Kitchen, 302 George St., New Bruns-

wick NJ. (732) 640-0553. www.increstaurant.com

Iridium, 1650 Broadway, 212-582-2121, iridiumjazzclub.com

Jazz 966, 966 Fulton St., Brooklyn, NY, 718-638-6910

Jazz at Lincoln Center, 33 W. 60th St., 212-258-9800, jalc.org

Frederick P. Rose Hall, Broadway at 60th St., 5th Floor

Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, Reservations: 212-258-9595

Rose Theater, Tickets: 212-721-6500, The Allen Room,

Tickets: 212-721-6500

Jazz Gallery, 1160 Bdwy, (212) 242-1063, jazzgallery.org

The Jazz Spot, 375 Kosciuszko St. (enter at 179 Marcus Garvey

Blvd.), Brooklyn, NY, 718-453-7825, thejazz.8m.com

Jazz Standard, 116 E. 27th St., 212-576-2232, jazzstandard.net

Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St & Astor Pl.,

212-539-8778, joespub.com

John Birks Gillespie Auditorium (see Baha’i Center)

Jules Bistro, 65 St. Marks Pl, 212-477-5560, julesbistro.com

Kasser Theater, 1 Normal Av, Montclair State College,

Montclair, 973-655-4000, montclair.edu

Key Club, 58 Park Pl, Newark, NJ, 973-799-0306,

keyclubnj.com

Kitano Hotel, 66 Park Ave., 212-885-7119. kitano.com

Knickerbocker Bar & Grill, 33 University Pl., 212-228-8490,

knickerbockerbarandgrill.com

Knitting Factory, 74 Leonard St, 212-219-3132, knittingfacto-

ry.com

Langham Place — Measure, Fifth Avenue, 400 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10018, 212-613-8738, langhamplacehotels.com

La Lanterna (Bar Next Door at La Lanterna), 129 MacDougal

St, New York, 212-529-5945, lalanternarcaffe.com

Le Cirque Cafe, 151 E. 58th St., lecirque.com

Le Fanfare, 1103 Manhattan Ave., Brooklyn. 347-987-4244.

www.lefanfare.com

Le Madeleine, 403 W. 43rd St. (betw 9th & 10th Ave.), New

York, New York, 212-246-2993, lemadeleine.com

Les Gallery Clemente Soto Velez, 107 Suffolk St, 212-260-

4080

Lexington Hotel, 511 Lexington Ave. (212) 755-4400.

www.lexinghotelnyc.com

Live @ The Falcon, 1348 Route 9W, Marlboro, NY 12542,

Living Room, 154 Ludlow St. 212-533-7235, livingroomny.com

The Local 269, 269 E. Houston St. (corner of Suffolk St.), NYC

Makor, 35 W. 67th St., 212-601-1000, makor.org

Lounge Zen, 254 DeGraw Ave, Teaneck, NJ, (201) 692-8585,

lounge-zen.com

Maureen’s Jazz Cellar, 2 N. Broadway, Nyack NY. 845-535-

3143. maureensjazzcellar.com

Maxwell’s, 1039 Washington St, Hoboken, NJ, 201-653-1703

McCarter Theater, 91 University Pl., Princeton, 609-258-2787,

mccarter.org

Merkin Concert Hall, Kaufman Center, 129 W. 67th St., 212-

501-3330, ekcc.org/merkin.htm

Metropolitan Room, 34 West 22nd St NY, NY 10012, 212-206-

0440

Mezzrow, 163 West 10th Street, Basement, New York, NY

10014. 646-476-4346. www.mezzrow.com

Minton’s, 206 W 118th St., 212-243-2222, mintonsharlem.com

Mirelle’s, 170 Post Ave., Westbury, NY, 516-338-4933

MIST Harlem, 46 W. 116th St., myimagestudios.com

Mixed Notes Café, 333 Elmont Rd., Elmont, NY (Queens area),

516-328-2233, mixednotescafe.com

Montauk Club, 25 8th Ave., Brooklyn, 718-638-0800,

montaukclub.com

Moscow 57, 168½ Delancey. 212-260-5775. moscow57.com

Muchmore’s, 2 Havemeyer St., Brooklyn. 718-576-3222.

www.muchmoresnyc.com

Mundo, 37-06 36th St., Queens. mundony.com

Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Ave. (between

103rd & 104th St.), 212-534-1672, mcny.org

Musicians’ Local 802, 332 W. 48th, 718-468-7376

National Sawdust, 80 N. 6th St., Brooklyn. 646-779-8455.

www.nationalsawdust.org

Newark Museum, 49 Washington St, Newark, New Jersey

07102-3176, 973-596-6550, newarkmuseum.org

New Jersey Performing Arts Center, 1 Center St., Newark, NJ,

07102, 973-642-8989, njpac.org

New Leaf Restaurant, 1 Margaret Corbin Dr., Ft. Tryon Park.

212-568-5323. newleafrestaurant.com

New School Performance Space, 55 W. 13th St., 5th Floor

(betw 5th & 6th Ave.), 212-229-5896, newschool.edu.

New School University-Tishman Auditorium, 66 W. 12th St.,

1st Floor, Room 106, 212-229-5488, newschool.edu

New York City Baha’i Center, 53 E. 11th St. (betw Broadway

& University), 212-222-5159, bahainyc.org

North Square Lounge, 103 Waverly Pl. (at MacDougal St.),

212-254-1200, northsquarejazz.com

Oak Room at The Algonquin Hotel, 59 W. 44th St. (betw 5th

and 6th Ave.), 212-840-6800, thealgonquin.net

Oceana Restaurant, 120 West 49th St, New York, NY 10020

212-759-5941, oceanarestaurant.com

Orchid, 765 Sixth Ave. (betw 25th & 26th St.), 212-206-9928

The Owl, 497 Rogers Ave, Bklyn. 718-774-0042. www.theowl.nyc Palazzo Restaurant, 11 South Fullerton Avenue, Montclair. 973

-746-6778. palazzonj.com

Priory Jazz Club: 223 W Market, Newark, 07103, 973-639-

7885

Proper Café, 217-01 Linden Blvd., Queens, 718-341-2233

Prospect Park Bandshell, 9th St. & Prospect Park W., Brook-

lyn, NY, 718-768-0855

Prospect Wine Bar & Bistro, 16 Prospect St. Westfield, NJ,

Clubs, Venues & Jazz ResourcesClubs, Venues & Jazz Resources

— Anton Chekhov

“A system of morality which is based on relative emotional values is a mere

illusion, a thoroughly vulgar conception which has nothing sound in it and nothing true.”

— Socrates

11 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880 October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com

908-232-7320, 16prospect.com, cjayrecords.com

Red Eye Grill, 890 7th Av (56th), 212-541-9000, redeye-

grill.com

Ridgefield Playhouse, 80 East Ridge, parallel to Main St.,

Ridgefield, CT; ridgefieldplayhouse.org, 203-438-5795

Rockwood Music Hall, 196 Allen St, 212-477-4155

Rose Center (American Museum of Natural History), 81st St.

(Central Park W. & Columbus), 212-769-5100, amnh.org/rose

Rose Hall, 33 W. 60th St., 212-258-9800, jalc.org

Rosendale Café, 434 Main St., PO Box 436, Rosendale, NY

12472, 845-658-9048, rosendalecafe.com

Rubin Museum of Art - “Harlem in the Himalayas”, 150 W.

17th St. 212-620-5000. rmanyc.org

Rustik, 471 DeKalb Ave, Brooklyn, NY, 347-406-9700,

rustikrestaurant.com

St. Mark’s Church, 131 10th St. (at 2nd Ave.), 212-674-6377

St. Nick’s Pub, 773 St. Nicholas Av (at 149th), 212-283-9728

St. Peter’s Church, 619 Lexington (at 54th), 212-935-2200,

saintpeters.org

Sasa’s Lounge, 924 Columbus Ave, Between 105th & 106th St.

NY, NY 10025, 212-865-5159, sasasloungenyc.yolasite.com

Savoy Grill, 60 Park Place, Newark, NJ 07102, 973-286-1700

Schomburg Center, 515 Malcolm X Blvd., 212-491-2200,

nypl.org/research/sc/sc.html

Shanghai Jazz, 24 Main St., Madison, NJ, 973-822-2899,

shanghaijazz.com

ShapeShifter Lab, 18 Whitwell Pl, Brooklyn, NY 11215

shapeshifterlab.com

Showman’s, 375 W. 125th St., 212-864-8941

Sidewalk Café, 94 Ave. A, 212-473-7373

Sista’s Place, 456 Nostrand, Bklyn, 718-398-1766, sistas-

place.org

Skippers Plane St Pub, 304 University Ave. Newark NJ, 973-

733-9300, skippersplaneStpub.com

Smalls Jazz Club, 183 W. 10th St. (at 7th Ave.), 212-929-7565,

SmallsJazzClub.com

Smith’s Bar, 701 8th Ave, New York, 212-246-3268

Sofia’s Restaurant - Club Cache’ [downstairs], Edison Hotel,

221 W. 46th St. (between Broadway & 8th Ave), 212-719-5799

South Gate Restaurant & Bar, 154 Central Park South, 212-

484-5120, 154southgate.com

South Orange Performing Arts Center, One SOPAC

Way, South Orange, NJ 07079, sopacnow.org, 973-313-2787

Spectrum, 2nd floor, 121 Ludlow St.

Spoken Words Café, 266 4th Av, Brooklyn, 718-596-3923

Stanley H. Kaplan Penthouse, 165 W. 65th St., 10th Floor,

212-721-6500, lincolncenter.org

The Stone, Ave. C & 2nd St., thestonenyc.com

Strand Bistro, 33 W. 37th St. 212-584-4000

SubCulture, 45 Bleecker St., subculturenewyork.com

Sugar Bar, 254 W. 72nd St, 212-579-0222, sugarbarnyc.com

Swing 46, 349 W. 46th St.(betw 8th & 9th Ave.),

212-262-9554, swing46.com

Symphony Space, 2537 Broadway, Tel: 212-864-1414, Fax: 212

- 932-3228, symphonyspace.org

Tea Lounge, 837 Union St. (betw 6th & 7th Ave), Park Slope,

Broooklyn, 718-789-2762, tealoungeNY.com

Terra Blues, 149 Bleecker St. (betw Thompson & LaGuardia),

212-777-7776, terrablues.com

Threes Brewing, 333 Douglass St., Brooklyn. 718-522-2110.

www.threesbrewing.com

Tito Puente’s Restaurant and Cabaret, 64 City Island Avenue,

City Island, Bronx, 718-885-3200, titopuentesrestaurant.com

Tomi Jazz, 239 E. 53rd St., 646-497-1254, tomijazz.com

Tonic, 107 Norfolk St. (betw Delancey & Rivington), Tel: 212-

358-7501, Fax: 212-358-1237, tonicnyc.com

Town Hall, 123 W. 43rd St., 212-997-1003

Triad Theater, 158 W. 72nd St. (betw Broadway & Columbus

Ave.), 212-362-2590, triadnyc.com

Tribeca Performing Arts Center, 199 Chambers St, 10007,

[email protected], tribecapac.org

Trumpets, 6 Depot Square, Montclair, NJ, 973-744-2600,

trumpetsjazz.com

Turning Point Cafe, 468 Piermont Ave. Piermont, N.Y. 10968

(845) 359-1089, http://turningpointcafe.com

Urbo, 11 Times Square. 212-542-8950. urbonyc.com

Village Vanguard, 178 7th Ave S., 212-255-4037

Vision Festival, 212-696-6681, [email protected],

Watchung Arts Center, 18 Stirling Rd, Watchung, NJ 07069,

908-753-0190, watchungarts.org

Watercolor Café, 2094 Boston Post Road, Larchmont, NY

10538, 914-834-2213, watercolorcafe.net

Weill Recital Hall, Carnegie Hall, 57th & 7th Ave, 212-247-

7800

Williamsburg Music Center, 367 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn,

NY 11211, (718) 384-1654 wmcjazz.org

Zankel Hall, 881 7th Ave, New York, 212-247-7800

Zinc Bar, 82 West 3rd St.

RECORD STORES

Academy Records, 12 W. 18th St., New York, NY 10011, 212-

242-3000, http://academy-records.com

Downtown Music Gallery, 13 Monroe St, New York, NY

10002, (212) 473-0043, downtownmusicgallery.com

Jazz Record Center, 236 W. 26th St., Room 804,

212-675-4480, jazzrecordcenter.com

MUSIC STORES

Roberto’s Woodwind & Brass, 149 West 46th St. NY, NY

10036, 646-366-0240, robertoswoodwind.com

Sam Ash, 333 W 34th St, New York, NY 10001

Phone: (212) 719-2299 samash.com

Sadowsky Guitars Ltd, 2107 41st Avenue 4th Floor, Long

Island City, NY 11101, 718-433-1990. sadowsky.com

Steve Maxwell Vintage Drums, 723 7th Ave, 3rd Floor, New

York, NY 10019, 212-730-8138, maxwelldrums.com

SCHOOLS, COLLEGES, CONSERVATORIES 92nd St Y, 1395 Lexington Ave, New York, NY 10128 212.415.5500; 92ndsty.org Brooklyn-Queens Conservatory of Music, 42-76 Main St., Flushing, NY, Tel: 718-461-8910, Fax: 718-886-2450 Brooklyn Conservatory of Music, 58 Seventh Ave., Brooklyn, NY, 718-622-3300, brooklynconservatory.com City College of NY-Jazz Program, 212-650-5411, Drummers Collective, 541 6th Ave, New York, NY 10011, 212-741-0091, thecoll.com Five Towns College, 305 N. Service, 516-424-7000, x Hills, NY Greenwich House Music School, 46 Barrow St., Tel: 212-242- 4770, Fax: 212-366-9621, greenwichhouse.org Juilliard School of Music, 60 Lincoln Ctr, 212-799-5000 LaGuardia Community College/CUNI, 31-10 Thomson Ave., Long Island City, 718-482-5151 Lincoln Center — Jazz At Lincoln Center, 140 W. 65th St., 10023, 212-258-9816, 212-258-9900 Long Island University — Brooklyn Campus, Dept. of Music, University Plaza, Brooklyn, 718-488-1051, 718-488-1372 Manhattan School of Music, 120 Claremont Ave., 10027, 212-749-2805, 2802, 212-749-3025 NJ City Univ, 2039 Kennedy Blvd., Jersey City, 888-441-6528 New School, 55 W. 13th St., 212-229-5896, 212-229-8936 NY University, 35 West 4th St. Rm #777, 212-998-5446 NY Jazz Academy, 718-426-0633 NYJazzAcademy.com Princeton University-Dept. of Music, Woolworth Center Musi-cal Studies, Princeton, NJ, 609-258-4241, 609-258-6793 Queens College — Copland School of Music, City University of NY, Flushing, 718-997-3800 Rutgers Univ. at New Brunswick, Jazz Studies, Douglass Campus, PO Box 270, New Brunswick, NJ, 908-932-9302 Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies, 185 University Avenue, Newark NJ 07102, 973-353-5595

newarkrutgers.edu/IJS/index1.html SUNY Purchase, 735 Anderson Hill, Purchase, 914-251-6300 Swing University (see Jazz At Lincoln Center, under Venues) William Paterson University Jazz Studies Program, 300 Pomp-ton Rd, Wayne, NJ, 973-720-2320

RADIO WBGO 88.3 FM, 54 Park Pl, Newark, NJ 07102, Tel: 973-624- 8880, Fax: 973-824-8888, wbgo.org WCWP, LIU/C.W. Post Campus WFDU, http://alpha.fdu.edu/wfdu/wfdufm/index2.html WKCR 89.9, Columbia University, 2920 Broadway Mailcode 2612, NY 10027, 212-854-9920, columbia.edu/cu/wkcr

ADDITIONAL JAZZ RESOURCES Big Apple Jazz, bigapplejazz.com, 718-606-8442, [email protected] Louis Armstrong House, 34-56 107th St, Corona, NY 11368, 718-997-3670, satchmo.net Institute of Jazz Studies, John Cotton Dana Library, Rutgers- Univ, 185 University Av, Newark, NJ, 07102, 973-353-5595 Jazzmobile, Inc., jazzmobile.org Jazz Museum in Harlem, 104 E. 126th St., 212-348-8300, jazzmuseuminharlem.org Jazz Foundation of America, 322 W. 48th St. 10036, 212-245-3999, jazzfoundation.org New Jersey Jazz Society, 1-800-303-NJJS, njjs.org New York Blues & Jazz Society, NYBluesandJazz.org Rubin Museum, 150 W. 17th St, New York, NY, 212-620-5000 ex 344, rmanyc.org.

“It is curious that physical courage should be so common in the world

and moral courage so rare.”

— Mark Twain

www.PressToRelease.com | MusicPressReleaseDistribution.com | 215-600-1733

PAY ONLY FOR

RESULTS

PUBLICITY! Get Hundreds Of Media Placements —

ONLINE — Major Network Media & Authority Sites & OFFLINE — Distribution To 1000’s of Print & Broadcast

Networks To Promote Your Music, Products & Performances In As Little As 24 Hours To Generate

Traffic, Sales & Expanded Media Coverage!

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 12 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

Interview and photos by Ken Weiss Bertha Hope-Booker [November 8, 1936, Los Angeles, CA], an accomplished pianist and composer, continues to be active, leading her bands at the tender age of 84. After a child-hood in Los Angeles, where Hope trained under Richie Powell and befriended future stars Eric Dolphy and Billy Higgins, she mar-ried and collaborated with luminary pianist Elmo Hope until his passing in 1967. Since that time, Hope has promoted and covered the work of her late husband, much of the time with the assistance of her second husband, the late, standout bassist Walter Booker, in vari-ous groups, as well as focused on her own work, and released a number of highly valued recordings with the help of Jimmy Cobb, Jun-ior Cook, Eddie Henderson, , Billy Higgins and Walter Booker. She has also performed with Dizzy Gillespie, Frank Foster, Nat Ad-derley, and Philly Joe Jones. Hope co-founded Jazzberry Jam, an influential all-female band in 1978. This interview was done by telephone on March 21-22, 2020, as life paused for the start of the COVID-19 pan-demic. Bertha Hope can be found playing every Sunday in New Rochelle, New York at ALVIN and FRIENDS for brunch.

Jazz Inside Magazine: We’re doing inter-view by phone rather than in person because the Corona virus pandemic has started. How are you feeling at this time? Bertha Hope: I’m feeling trapped. Some days I’m agitated and other days I’m really work-ing through it. I’m trying to be as consistent

as possible, although that’s not always easy. I think there’s very little that I will accomplish out of the things I wanted to. Consistency is one of them. I think not enough people are taking this pandemic seriously enough be-cause they’ve never seen anything like this before and that’s sad because those people endanger my life and many other lives. JI: What are you referring to when you say you aren’t going to accomplish all the things you’d like to do? BH: I mean things that I have not paid atten-tion to before because of the gigs, the prepara-tion for the gigs, writing music and practicing, and being on top of my game, as much as I could be. Those all took precedence in my life. Some of the things I want to do are fami-ly oriented. I also want to write a little bit more music. I’ve been working on a piece for a long time that’s kind of built on my life. I’m trying to write pieces that reflect the stages of my life. I’m also trying to get my music, and all of Elmo’s music, organized in one space. Now that there’s no performances or dead-lines [due to the pandemic], I am using my time differently, and it’s making a difference.

JI: Would you talk about your playing style? You don’t dwell on flashy technical displays. What’s important to you? BH: I try to tell a story, it’s not a planned story. I try to use what information I have, or if the song has a particular meaning to me, I want to be able to convey to the audience

what the history of the song is for me. I want them to be able to feel something about what I felt when I wrote it or when I learned it. The songs all have a lot of moving parts. I don’t have fabulous technique. My hands are small. I can barely reach an octave. I have to take all those things into consideration in how I sound and what the song gives to me, and what I can give back to my listeners. It’s not about flash. I don’t have any flashy technique, that’s very true. I did not learn a flashy technique style when I was taking formal piano lessons. I learned a basic, secure kind of sound tech-nique to get a good sound out of the piano, and I didn’t take piano lessons long enough to acquire a huge classical repertoire, so my technique is very basic. I’m learning more and more as I’ve taken more lessons later in life to expand on the idea that I have small hands and there are different ways to use my hands, a different way to manipulate my arms, and get more sound out of the piano. JI: When was the last time you took a piano lesson? BH: I started taking lessons again about 3 years ago from a classically trained pianist, whose hands were about the same size as mine. She taught me a different rotation to my wrists, which puts the fingers in an angle on the keyboard. JI: You mentioned being attracted to songs that you can tell a story from. How has play-ing your own songs or standards changed from your early career to the current day? Has their interpretation changed over time? BH: Yes, I think as I’ve gained more knowledge about life, for one thing, more on the idea of taking my time to examine what makes the song up. What are the elements of the song? What’s the tonal quality? Where’s it moving, where’s it going? What is it giving to me today? What is it giving to me on the pi-ano that I’m playing? What can I express on this piano that I couldn’t express on a lesser or a better piano? All of those things come into how I’m able to interpret the song. A lot of it is what the instrument has to offer. Piano players are at the distinct disadvantage be-cause this is not a personal instrument, unless you are somebody who moves their piano around. I know Oscar Peterson moved his personal piano around, but not many people are able to do that. I always say you have to marry a piano that you’re going to play. You have to find out quickly what this piano is going to give you and what you can give it in order to see what you are going to be able to say to the listening audience about that mar-riage. You have to learn that at a soundcheck, perhaps, and that’s not always easy. I’ve had people tell me after hearing me in different settings about how different the experience was for them because they had no idea that I could play with that kind of power because they heard me on a crappy piano first, and

(Continued on page 14)

“I always say you have to marry a piano that you’re going to play. You have to

find out quickly what this piano is going to give you and what you can give it in order to see what you are

going to be able to say to the listening audience about that marriage.”

Bertha Hope

I call myself a survivor

INTERVIEWINTERVIEW

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 14 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

then they heard me on a nine-foot Baldwin. JI: What are the benefits and disadvantages of you having perfect pitch? BH: [Laughs] The benefits are, and I guess you could ask if perfect is perfect everywhere, but I can say that it’s perfect in the Western, classical style of music. I can really hear and learn a lot of things by examining what they are with just my ears. The benefits are that I have learned a lot of music without even see-ing it because I can hear it and translate it accurately to the piano. The disadvantages of that are in writing, because if you can’t hear it, then it doesn’t exist for your ears, and you really have to have the education to know what you’re doing. I am able to read music very well, however. Some people say I don’t really have perfect pitch because perfect pitch doesn’t really exist, and I’m beginning to be-lieve that that could possibly be true, but what I have is something that allows me to repeat

what I hear. This all started when I was three and I don’t really know the science behind it. I feel that it’s a gift and I’m grateful for the gift, believe me. JI: You hail from a family of artists. What was your childhood like? BH: I grew up in Los Angeles. My father’s family settled there from Arkansas and South Carolina, and my father moved there to be with them when he got out of the army. He discovered in the army that he had a wonder-ful voice and he became a contemporary of Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson and Roland Hayes. Those were the three most exposed black performers of that era. He had a great career. He traveled all over the world during that era – from 1915 until the banks crashed in 1929. He had a dramatic baritone voice and sang Italian bel canto, German lieder, English ballads, and the negro spirituals. He also got into a movie career later in the ‘40s, after he stopped traveling. I grew up listening to all of that music. My mother was an opera buff and a ballet dancer. Her dream was to open a dancing school in St. Louis, but she met my father along the way to her dream, and they married in England where he was managing

[the stage show] Show Boat. He then came to this country to put the cast together for that production in this country. It was a very rich experience at home. At school, there were many music classes from sixth grade to twelfth grade in the Los Angeles public schools. I started playing violin in the seventh grade. I never played it very well, but I learned how to read. Then I played viola. Eve-ry year, the teacher would elevate you to an-other instrument to take the place of some-body graduating. I had a great time. I played clarinet and all of the percussion instruments, and by the way, clarinet and flute were the only wind instruments that were allowed at that time for girls. No brass instrument of any kind was allowed. I played well enough that at age twelve, my father hired me to play church concerts with him in Los Angeles. JI: Your father was friendly with stars such as Sidney Bechet, Josephine Baker, Paul Robe-son and Jack Johnson. Did you have any meaningful contact with them? BH: No, out of all those [well-known] people the only one I met was Eubie Blake, and I met him when he was in his mid-nineties here in

New York. My father and he were great friends. They were in Europe together at the same time, probably playing the same circuit and command performances for English roy-alty. The other people I met briefly [as a child with my father] when they came to town. JI: What were your early jazz experiences that led you to a career in music? BH: My first gig that I remember in Los An-geles was with Johnny Otis’ band. Little Es-ther Phillips was the singer in that band. I think she was fifteen and I was sixteen, may-be. We played on the weekends with our parent’s permission. Johnny Otis had to con-vince my parents to let me work in his band

and he had to have an escort bring me home right after the job. I’ve always loved big bands and the power that a big band gener-ates. I had pretty much decided at that age that I wanted to pursue jazz in a very focused way. The next gig that had a big impact on me was with Vi Redd. She was the only woman that I ever met who was playing a saxophone at that time. There were others in Los Angeles, I’ve learned now, but I did not meet them at that time. I knew about Clora Bryant and Melba Liston, but they were not people that came into my space. I always admired Vi because she sang and played the saxophone, and she was a great leader, very nurturing. That was my beginning. After that, I put together a quartet of my own that was kind of experi-mental with vibist Dave Pike, and drummer Billy Higgins, or more often, John Pickens. It was only a rehearsal band. Then I worked, when I was very young, with Teddy Edwards. That turned out to be a real challenge [Laughs] because he played such a bluesy horn and my ears were continually ablaze with the things that I learned from him. All these experiences had a great impact on me. JI: Hearing a Bud Powell recording at age 15

was also a turning point in your life. What did you hear in his playing that so inspired you? BH: It was an introduction to a different use of chordal material. I was listening to Duke Ellington records at the time. I had seen Bud live but it was the record, and not the perfor-mance, because by that time he was not per-forming as well as he had done on his records. On the record was a piece called “Un Poco Loco,” and that piece kept me up all night. [Laughs] That was what I considered to be the turning point in what was possible. I think it was an introduction of a new harmonic that I hadn’t been aware of before, and I stayed up all night until I could really find it in all the keys and analyze that piece of music, as much as I could. I really realized the work that it was gonna take to be able to approximate any-thing close to that kind of sound. JI: Billy Higgins was a high school classmate of yours who shared your interest in jazz. What were your early experiences with the future drum legend? BH: Billy was one of three people who were in our group of kids who really liked jazz and

(Continued from page 12)

(Continued on page 16)

“Billy [Higgins] told me that the [Ornette Coleman] band didn’t have a piano player in it but that I should come and listen to it anyway to hear

what they were doing. That was a revelation. They played until they wore themselves thin. That’s what people did at that time. They used the whole day and night to work through the music and it was very intense.”

— Anton Chekhov

“Encroachment of freedom will not come

about through one violent action or movement but will come about

through a series of actions that appear to be unrelated and coincidental, but

that were all along systematically planned for dictatorship.”

— John Adams, 2nd President

Bertha Hope

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 15 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

Concert Halls, Festivals, Clubs, Promoters

PAY ONLY FOR RESULTS PAY ONLY FOR RESULTS CONCERT & EVENT MARKETING!CONCERT & EVENT MARKETING!

Fill The House In Hours For

Your Next Performance

rketingrketing Get Your Phones Ringing NOW!Get Your Phones Ringing NOW!

CALL: 215-887-8880 www.SellMoreTicketsFast.com

Lightning Fast, Way Better Results & Far Less Expensive Than Lightning Fast, Way Better Results & Far Less Expensive Than

DirectDirect--Mail, Print, Radio & TV AdsMail, Print, Radio & TV Ads——Comprehensive Analytics!Comprehensive Analytics!

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 16 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

studied it. We listened to Duke Ellington, Miles, Charlie Parker, and Bud Powell. Short-ly after that, Billy was beginning to rehearse with Ornette [Coleman], Don Cherry, and Charlie Haden, and I used to hang out at Billy’s place. I was a guest fly on the wall, listening to that band with no piano as the foundation. It was an invitation to hear what was happening in Ornette’s mind. I had heard Ornette way before I was in his company, and he had sounded much closer to Charlie Parker’s origins than he ended up sounding with his own harmolodic theoretical point of view. I was able to listen to them rehearse quite a bit. Billy told me that the band didn’t have a piano player in it but that I should come and listen to it anyway to hear what they were doing. That was a revelation. They played until they wore themselves thin. That’s what people did at that time. They used the whole day and night to work through the mu-sic and it was very intense. JI: What did you think about what Ornette

was doing at those rehearsals? Did you under-stand what he was doing with the band? BH: I heard it as something fresh, something unexamined. This is really funny – Billy gave me one of the song’s chord changes. It was a sketch of one of the songs they were about to play. So, I’m looking at the music, and I was beginning to really understand how to read chord changes, and they were just written symbolically. I couldn’t understand the move-

ment that the music was making in accord-ance to what I was looking at on the paper. I don’t know if I formed a real opinion about the music, I just felt that it was a new direc-tion. There were parts of it that sounded like parts were missing, and I always suspected that it had an underlining structure that I just couldn’t connect to. In later years, the more I listened to Ornette, I guess, the more free my own ideas about music had become, and it didn’t sound so foreign after all. I was really very young and impressionable when I first heard him, and he was looking for his own direction. It was an exciting time to be able to hear them because we were all young and he was definitely turning another page in the music world. JI: While studying theory and harmony at Los Angeles City College you befriended your neighbor and fellow student Eric Dolphy? Talk about that experience. BH: Dolphy was brilliant. He encouraged me to practice, practice scales. We didn’t have the opportunity to practice together but he was a big influence because he used to talk to me a lot. We took classes together, we studied har-

mony together in the first year. We carpooled together. One day he drove his car, and the next day I drove mine to conserve gas. He was intense, very, very focused. He taught me to really appreciate the idea that you needed to put in the hard work involved with being the best that you could be at this. And the scales, above all, were the foundation of what you needed to know, and I thank him for that. JI: You used to listen to him rehearse with

Max Roach’s band. BH: That was the beginning of the Max Roach and Clifford Brown band. They were just so focused on what they were doing. They would play until they couldn’t play anymore. It was a very intense experience. I keep on using that word but it’s the one that describes the theme best for me. They were all about the music and trying to get it right and they sounded fabulous to my young ears. I didn’t realize then that I was witnessing history. JI: How did you come to study with Richie Powell? BH: He was the pianist in the Max Roach / Clifford Brown band. I thought I would be extremely lucky if he were to say yes to teach me, because I really didn’t think that he would. I got enough courage together to ask him and he said yes. I was listening to them practice so that’s how that happened. And because they were rehearsing, at Eric’s house, which was not that far from mine, he was able to come to my house and give me lessons. I think that if I hadn’t met him [through Eric], I wouldn’t have been that fortunate. JI: What did Powell stress in his teachings? BH: He mostly stressed, and I think he re-spected the fact that my hands are small, alt-hough he never said that, but what he stressed was moving voicings in and out, voice leading a real clear passage from one chord to the next. He really did teach me the inversions of all of the keys, and how to voice chords and how to move them and make them have ten-sion and release, and all the elements that a chord needs to move from one place to the other. He didn’t go over any particular theory or technique, it was really about the theory that I learned from him. I had the classical technique that I’ve been able to use from my classical instructions. He didn’t sound like Bud, but he certainly had a lot of the same information that Bud had. I felt really fortu-nate to just be exposed to that. How much of that I’ve been able to really use and show that this is my background, I don’t know, but I thought I couldn’t do better at that point then having Richie teach me. I took lessons for maybe five months. A major part of the lesson was being able to hear him playing what he had just shown me. It was just a joy to be able to hear him play. My lessons lasted from sev-en to eight, and he would play my piano from eight to eleven before he would leave. Some-times he would have dinner with my family. I just sat on the couch and listened to him play. It was like a live concert in my living room and I learned a lot by listening. JI: When is the last time you ever took a pi-ano lesson? BH: About six months ago I took a series of lessons. I was able to fit it into my schedule

(Continued from page 14)

(Continued on page 18)

Bertha Hope

“I had other things that I needed to examine – how I got into what I got into, how Elmo’s death had affected me, and how I had chosen to cope with all these things. I couldn’t concentrate on the piano. I was getting ready to re-orient my

thinking that the music had so much to do with both my joy and my despair. I decided to just

give the piano away ... I wanted it to be used by somebody who would appreciate it. A friend

said, “I’ll take the piano off your hands ... This is temporary and once it leaves, you’re gonna

want this piano back, and you’ll appreciate it in a way you didn’t before.”

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 18 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

and my financial situation too. I started taking lessons a year ago because I had carpal tunnel. I still do, and I’m really very hesitant to have surgery on my hand. So, I have been doing therapy, and I took the lessons to see if I could alleviate the pain by using my hand in a dif-ferent way. I’ve been using the technique that she showed me and they’ve been very helpful. JI: Have you taken lessons from other noted pianists? BH: Not really. A few people turned me down, and I will never know the reason. I won’t mention their names but they’re very noted, and they both said, “You just need to go home and practice.” I think one of them did not want to give me lessons because I was married to Elmo. The people who taught me the most were the musicians playing in [Walter] Booker’s studio. They taught me an enormous amount, just by watching them play for hours. I asked them questions and they suggested things. I sat down next to them – Larry Willis, John Hicks and Ronnie Mat-thews, and that was the best way to learn. JI: Bud Powell was your biggest influence. What was the extent of your contact with him? BH: Unfortunately, I did not get a chance to know him in any real way. I heard him live in Los Angeles in a club that had mirrored ceil-ings and walls and it was very clear that Bud was not well. I wanted to tell him how much I enjoyed his music and was trying to learn from him, but it was clear that he wasn’t go-ing to be approachable. I was still in high school. The next time I encountered him was with his guardian, Francis Paudras, who had brought him back here to the United States. He was staying with Thelonious Monk and he wanted to see Elmo. That’s what Nellie told me, but they never made time for him to see Elmo. It turned out that Bud escaped their surveillance and it hit the newspapers and TV that the police were looking for him because he had gotten away from his caretaker. Well, he was on his way to Elmo’s house. He went to Elmo’s mother’s house, but we had moved to another part of the Bronx. Elmo was walk-ing from his house to his mother’s house, and Bud was walking from Elmo’s mother’s house to our house, and they met in the street. Elmo brought him to our house. He was really debilitated by that time. We lived in a second-floor walk-up and it took him almost a half an hour to get up the steps. That was the second time I met him. It was my fantasy to ask him all kinds of questions and sit down beside him and watch him play, but that didn’t happen. JI: What were your plans on graduation from Los Angeles City College?

BH: I was probably going to try to launch myself into the music scene there. I didn’t graduate. I didn’t finish, but if I had, that’s probably what I would have done. I may have even gone a whole different way and gotten into the studios. My plan was to put a band together and play and write. I ended up taking a road trip instead, and that was a learning experience. That’s what really brought me to New York. I eventually finished but I didn’t get my music degree. Several times over the years I thought very seriously about going back to school for a music degree, but I de-clined. What I’ve learned during all of these years has been through other people mentor-ing me, and from other musicians, just by playing with them. That’s really been the way that I’ve acquired whatever I have, whatever way I’ve used my gifts have been because other people have bestowed their gifts on me. JI: Would you talk about meeting Elmo Hope in 1957 after he moved to Los Angeles? BH: I met him when he had just left Chet Baker’s band. They didn’t record together so people don’t know that history. That’s been lost because there aren’t any records. He worked that whole West coast circuit with Chet for a couple years, from Vancouver down the coast. Right after he left Chet, he was sort of a first call musician on the West coast. I met him when he was working with Sonny Rollins, who had come to town and picked up a rhythm section. Then Elmo worked with Dexter Gordon. He and I were friends for about eighteen months. We got to be really close before we got married. I had a car and I would take him and Dexter, or who-ever he was working with, to all their gigs, and we just grew to be really wonderful friends. Before I met him, I was furiously trying to learn some of his music by putting the record on and listening to it over and over and over again, and then sitting down and trying to play what I heard. I wasn’t privy to any of his transcriptions. The very first night I met him I was excited that I was really meet-ing this person whose records I was listening to and here he was in the flesh. I said to him that, “I’m learning some of your music,” and he looked at me with doubt. He had this ex-pression on his face. “You’re learning my music?” And it was hard to tell whether he was kidding, or he was amazed, or if he didn’t believe it. Harold Land was there, and he said to Harold, “She said that she’s learning my music,” and Harold said, “Well, maybe she is.” He just didn’t want to believe it, and I invited him after that gig to come to my house and hear me play so I could see for myself if I was really making any headway in getting it right or if I was delusional. [Laughs] He saw that I was serious about learning the music. He did correct a couple things. The order that I listened to the bebop pianists in, and when I say bebop pianists, I mean only Thelonious, Bud and Elmo. I heard Bud first, then Thelo-nious on record, and then I heard Elmo. And then I learned that they were all great friends

and shared an awful lot of information with each other in their playing and writing style. It was funny that I heard Elmo last and ended up being with him. I always found that an inter-esting alignment to think that he was the last of those three piano players that I grew to admire so much. JI: For those of us who never got to see him, what was it like to view an Elmo Hope perfor-mance? BH: He was a constant smoker. He’d always have a cigarette dangling out of his mouth. He closed his eyes and hunched over the piano. He had a monotone style of singing that he did sometimes, where he was singing along to the melody in his own head, and sometimes it escaped. He had a very deep speaking voice. He played with a lot of fire in some instances, while his ballads were really dreamy, melan-choly, really deep, dark ballads. He was really gracious. He was a small man who got a great sound out of the piano. He could hit the piano and make it sing, and he played with a great dynamic range. He played the full sweep of the piano. Sometimes he was given pianos to play that were badly worn in the middle regis-ter, so Elmo improvised at the top part of the piano exclusively or avoided the middle part of the piano altogether. He’d play the left hand in the lower register and the right hand in the higher register, so sometimes he was really challenged. He wasn’t always privy to the best pianos, and as I talked about earlier, about marrying a piano, and finding out what it can give you? He was very good at that. JI: How did life change for you after getting married to Elmo Hope in 1960? BH: It changed drastically. [Laughs] My daughter Monica was born at the end of 1960, and by that time we were living in the Bronx. I was working at the telephone company as an operator, which I did for a long time, while I was also working in the Jimmy Castor band. Around 1963 I got involved in drugs, which was really unfortunate. That was something that I did not see coming. In 1966, my third child Darryl was born. My drug use was a drastic change. I didn’t have very much knowledge about drugs, or drug addiction, or drug use. It didn’t exist in my world in L.A. at all. My parents didn’t drink or smoke, and I didn’t grow up with people where even alco-hol was in the house, so drug addiction really caught me by surprise. I managed, because Elmo died in his forties, in 1967, when my youngest child was not quite a year old, and his death really catapulted me into looking at what my life would be like if I were to contin-ue to pursue drugs. It was a rude awakening. It’s almost that the way I fell into drugs, and the way I got out, were cataclysmic, in a way. I just decided that I couldn’t see a life for my-self at all because Elmo was greatly involved in my drug usage. I didn’t see it without him, so I just stopped cold turkey almost immedi-ately. His death was such a blow. I just decid-

(Continued from page 16)

Bertha Hope

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 19 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880

ed that when he died that that was the end of my use of drugs. I just stopped. We were mar-ried seven years. It was a tumultuous seven years. There were some glorious moments, they were at the very beginning of the mar-riage. By the middle, [Laughs] I was just kind of overwhelmed, but the love didn’t disap-pear. My relationship to the drugs was some-thing that I didn’t think I could be a part of, but I became a part of it. I didn’t get to the point where I was totally destroyed by it, and I think the reason that I didn’t was because I quit as abruptly as I started. Since that time, I have not used any drugs at all. I quit in 1967. JI: It’s known that Elmo was a heroin user, is that what you were using also? BH: Yes. JI: Did you have concerns about Elmo’s drug use when you married him? BH: No, as I said I did not understand the dynamics of drugs or drug usage. I didn’t know what drugs did to people or what his life was like, so I didn’t have any concerns. I think I was just too young and naïve, and I didn’t ask any questions. That was unfortu-nate but I call myself a survivor. JI: Would you share some memories of Elmo Hope? BH: He never had a working band, as far as I know. I’m sure part of it was that he lost his cabaret card and so he wasn’t able to work in any place that served alcohol [in New York City]. Other people got their cabaret cards returned to them, but Elmo was not one of them, and that kept him out of clubs. That could very well be the reason he never devel-oped his own band. And whenever he had a record date, often he wrote music fresh music. He had a lot of material but would not use it for the date. I think one of the most interesting things was when he went to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, he would take a cab out there and he’d be writing the date, in the cab on the way to the studio. I wonder how many people did that? Many a song he wrote on his knees in the book he carried on the ride from the Bronx. When he got an idea, he would just scribble it on anything and compile it when he got some score paper together. JI: In 1964 the Elmo Hope Trio was playing at The Baby Grand, a New York club at 125th Street, when the then unknown Albert Ayler suddenly appeared, jumped on stage and start-ed blowing his saxophone for 20-30 minutes. Hope packed up and left the club. Did he say anything to you about this when he came home?

BH: I never heard about that. [Laughs] Albert Ayler? Well, this is a revelation to me. That’s incredible. I will tell you about another expe-rience that Elmo had. Charles Mingus hired Elmo for the Blue Coronet in Brooklyn for a date and they were to rehearse in the club. Mingus and the band and Elmo all got there before the performance, but the club was locked, and they couldn’t get in to practice. Mingus rehearsed the band in front of the Blue Coronet and he told Elmo, “Look, I can’t use you tonight because I can’t play this mu-sic without a rehearsal and I can’t give you your part, so you’re fired.” [Laughs] He came home livid from the rehearsal. JI: Your first recording work came on Elmo Hope’s Hope-full (1962, Riverside) album, where you played on three duets with him. How comfortable were you recording at that stage of your life?

BH: I was not comfortable at all. Although I had been playing in public for a while in other settings, I didn’t think I was ready pianistical-ly to play duets, or even to just play with him. I didn’t really think I belonged there. JI: How did you come to record those duets? Did Elmo talk you into it? BH: No, I think it was Orrin Keepnews and Johnny Griffin who thought it was going to be a good idea. I hadn’t had any experience play-ing with Johnny Griffin, we were just all friends. Johnny and Elmo were big friends and they played together. I think they thought it would be a good idea to record the two of us together but I never felt I was ready enough to do that album, but it has stood the test of time,

and I think that it’s probably novel, because there weren’t that many couples [that played together] at that time. People bring it up often, but I think I could have done a better job. Well, I always think I could have done a bet-ter job no matter when I record. Recording is not one of my favorite things. I’m extremely agitated in a recording studio, and that’s to-day. I was even more nervous then. JI: When did you feel confident of your skills as a performer? When did you feel you were able to stand your own on the New York jazz scene? BH: I can’t put a date on that. I don’t think there was ever a time when I said, ‘I’m ready.’ I just put bands together and kept on playing with people who were better than I was. I think with each band I learned some-thing different from the people that I was playing with. I learned how to be a communi-

cator, how to be more conscious of the band as a group where everybody has a voice. I listened to my first recordings and heard how selfish I was about soloing. I had to learn about making a record a more communal, democratic kind of experience. I’m always open to learning and being more aware of those things. I think, hopefully, I’m playing better now than I ever was because this is now, and there’s no going back. I’ve put a different quality of time into bands that I have. We rehearse, we practice together, I’m still working on Elmo’s music, and I have a steady band of five committed people who work on it with me. That’s very satisfying. I have a committed trio, and I’m playing new music and refreshing the old music. I hope I’m still evolving as an artist and as a person who plays the music, and I’m really hoping that today I play better than I did yesterday. I think I’ve had some great advantages to be able to do that, and as long as I’m on the plan-et, I really want to continue to evolve and grow and learn from my fellow musicians. That’s the most sincere learning I think you can get.

(Continued on page 20)

“Ultimate success is not directly related to early success,

if you consider that many successful people did not give clear evidence

of such promise in youth.”

- Robert Fritz, The Path Of Least Resistance

Bertha Hope

“I don’t think there was ever a time when I said, ‘I’m ready.’ I just put bands together and kept on playing with people who were better than I was. I think with each band I learned something different from the people that I

was playing with. I learned how to be a communicator, how to be more conscious of the band as a group where everybody has a voice.”

October 2021 Jazz Inside Magazine www.JazzInsideMagazine.com 20 To Advertise CALL: 215-887-8880