Before Folsom: The 12 Mile Creek Site and the Debate Over the Peopling of the Americas.

Transcript of Before Folsom: The 12 Mile Creek Site and the Debate Over the Peopling of the Americas.

1

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 51, No. 198, pp. x-xx, 2006

Matthew E. Hill Jr., 365 South Cloverdale Ave, #103, Los Angeles CA 90036; [email protected]

Before Folsom: The 12 Mile Creek Site and theDebate Over the Peopling of the Americas

Matthew E. Hill, Jr.Histories of American archaeology rightly point to the discoveries at the Folsom site as the turning

point in the debate of a Pleistocene peopling of North America. However, this was not the first site wherefluted projectile points were recovered in association with an extinct form of bison. In 1895 University ofKansas paleontologists excavated the 12 Mile Creek site in western Kansas and recovered an in situfluted projectile point with the remains of 13 Bison antiquus skeletons. The site is generally overlooked inthe histories of this debate. Published articles and unpublished personal letters reveal that 12 Mile Creekwas very influential to the Folsom excavators as well as a number of other important researchers. Itshows that the limited influence that 12 Mile Creek had on the anthropological community was notbecause of the loss of the projectile point from the site or difficulties in dating the site, but was instead dueto the manner in which the investigators presented their results. What differentiated the 12 Mile Creeksite from Folsom was that the investigators of the latter site allowed outside researchers to independentlyvalidate claims about the site’s age and the association between the artifacts and animal remains.

Keywords: history of archaeology, artifact-fauna association, Paleoindian

“IN MY HANDS”“In my hands (displaying a box of artifacts

[from the Folsom site]) I hold the answer to theantiquity of man in America” (Brown 1928:824).These words of Barnum Brown, noted paleontolo-gist and excavator of the Folsom site, symbolizedthe end of a debate that had been raging in NorthAmerica for nearly four decades: were humans inNorth America during the Pleistocene? The cur-rent paper does not review the history or impor-tance of the Folsom finds (e.g., Meltzer 1983, 1991,1994; Jackson and Thacker 1992), but instead dis-cusses the history of another site where human ar-tifacts were found in association with Pleistocenefauna more than 30 years before Folsom. The sitewas 12 Mile Creek where in 1896 paleontologistswith the University of Kansas recovered a flutedprojectile point with the remains of 13 Bisonantiquus skeletons along a small creek in LoganCounty, Kansas (Hill 1994, 1996, 2002; Rogersand Martin 1984; Sellards 1952; Stein 1984;

Williston 1897, 1902a, 1095; Yaple 1968) (Figure1).

Although at both sites fluted projectile pointswere recovered in association with multiple skel-etons of an extinct form of bison, 12 Mile Creekplayed no role in convincing the American archaeo-logical community of a long antiquity of humanoccupation of North America (Hofman and Gra-ham 1998; Meltzer 1991, 1994). This is despitethe fact that modern archaeologists (i.e., Brownand Logan 1987; Haynes 1993; Hofman 1994)accept the site as a valid late Pleistocene age kill.This paper explores some possible reasons whyFolsom was accepted and 12 Mile Creek was not.The history of 12 Mile Creek highlights the im-portant methodological and theoretical changes inarchaeology occurring at the turn of the 20th cen-tury that were necessary before the archaeologicalcommunity could accept the concept of a Pleis-tocene occupation of the Americas.

Using published sources and unpublished per-

2

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

sonal correspondence, I first outline the history ofinvestigation at the site and then describe andpresent contemporary researchers’ responses to thesite. Next, I describe how the primary investiga-tors of the Folsom site (i.e., Barnum Brown, JesseD. Figgins, and Harold Cook) were aware of thesite and believed that their work supported the ear-lier finds at 12 Mile Creek. At the end of this pa-per, I explore potential explanations for why thissite was not more influential to the larger archaeo-logical community.

THIRTY YEARS BEFORE FOLSOMIn the spring of 1895, Samuel Wendell

Williston, professor of Paleontology at the Uni-versity of Kansas, flush with $1500 of universityfunds, decided to field two summer work crews(Shor 1971) to search for fossils across the west-ern United States. The first party, headed byWilliston, headed off towards Lusk, Wyoming, insearch of Triceratops fossils (Kohl et al. 2004).The second crew, consisting of Williston’s twoassistants, Handel T. Martin and Terrell R. Overton,

went off to western Kansas where Williston hadpreviously investigated rich Cretaceous deposits(Shor 1971; Williston 1891, 1903).

While collecting fossils near the city of RussellSprings, Martin and Overton’s attention was drawnto the bank of Twelve Mile Creek, a small ephem-eral tributary of the Smoky Hill River, where a lo-cal resident, Charles Wood, had noticed some mam-mal teeth eroding out of a channel after a recentflood (McClung 1908:249). Recognizing that thebones came from an extinct form of bison and hop-ing to obtain a museum specimen, Martin andOverton began excavating around the exposure.Their work revealed a dense concentration of bi-son bones contained within a 60-cm-thick (2 ft)layer of fine blue-gray silt, which in turn was de-posited on a 10-cm-thick (4 in) sandy conglomer-ate. These deposits were situated in a slight de-pression cut into the underlying Cretaceous chalk(McClung 1908:250; Sellards 1952; Williston1902a, 1905). Overlying the bonebed was approxi-mately 6 m (20 ft) of loess (Williston 1902a).

By the end of the 1895 field season Martin

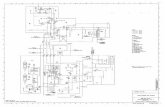

Figure 1. Map of the United State with the important sites mentioned in the text.

3

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

and Overton had uncovered approximately 40 m2

(15 to 20 ft by 25 ft) of the bison bonebed but stilldid not realize the deposit was an archaeologicalsite. The following year, after a heavy flood ex-posed more bones, Martin returned to the site andcontinued excavations (H. T. Martin to J. D.Figgins, letter, 30 December 1926, Jesse D. FigginsPapers, Colorado Museum of Natural History,Denver [JDF/CMNH]). During this year, Martinencountered a nearly complete bison skeleton about3 m from the edge of the Twelve Mile Creek, withits head pointed to the east, and lying on its rightside. When the right scapula of this specimen wasfinally removed it separated cleanly from the un-derlying matrix exposing a small projectile point(Williston 1905:314). When the point was re-moved, “it too left a perfect mold in the hard ma-trix” (Sellards 1952:47, quoting a 15 January 1918letter from H. T. Martin). The base of the pointwas apparently deeply buried while its tip wastouching the scapula. Martin immediately recog-nized that due to the orientation of the point it hadto have been “within the body of the animal at thetime of death, or have been lying on the surfacebeneath its body” (Williston 1905:315). Unfortu-nately, no drawing or photographs were made ofthe bonebed, and just a single drawing was madeof the point (Figure 2).

Loss of the Projectile PointSoon after the collection was brought to

Lawrence for processing and analysis, the pointwas stolen. The circumstances surrounding its dis-appearance are poorly recorded, so exactly whathappened is not known. The little that is knownabout the loss of the point comes from a series ofletters written many years after the events tookplace (Rogers 1984; Rogers and Martin 1985).

According to the letters, the point was stolenduring a public talk at Williston’s house a few yearsafter the excavation. Records at the University ofKansas archives (University of Kansas Archives:67/147/old & new club) indicate that this talk mighthave been part of the Old and New Club lectureseries, an eclectic lecture series given by Univer-sity of Kansas faculty to interested university andlocal community members. On January 21, 1899,Williston gave a talk on “The Antiquity of Man.”

The talk was reportedly attended by the uni-

versity chancellor and a number of prominent lo-cal citizens, some of whom were important finan-cial supporters of the university (C. W. Hibbard toE.H. Sellards, letter, 17 November 1945, ClaudeW. Hibbard Papers, University of Kansas Museumof Natural History, Lawrence [CWH/KUMNH]).As part of the talk, Williston placed the 12 MileCreek point, along with some other artifacts, in abox that was passed around the room for the audi-ence to inspect it. When the box of artifacts wasreturned, the 12 Mile Creek point was missing andnone in the crowd admitted to taking it. The chan-cellor and Williston were hesitant to accuse any-one of stealing it or to involve the police in thetheft, possibly because they were at that very timeattempting to raise money from university support-ers in order to establish a medical school in Kan-sas (Shor 1971). It would have been counterpro-ductive to have the police shake down the esteemed

Figure 2. Line drawing of projectile point recovered from the12 Mile Creek site (adapted from Williston 1905: 338) (scaleunknown).

4

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

members of this audience.When Martin was informed of the loss he was

very upset that Williston allowed people to leavewithout calling the police (C. W. Hibbard to E. H.Sellers, letter, 17 November 1945 CWH/KUMNH). Eventually, Martin grew to suspect alocal woman “who was crazy for old relics” thatlived outside Lawrence, Kansas. Martin claimedthat a friend of his saw the point in this woman’shouse (H. T. Martin to J. D. Figgins, letter, 30 De-cember 1926, JDF/CMNH). When the womandied, Martin reportedly examined artifact collec-tions she had donated to a local church and thecollege, but was never able to relocate the point.

Current Information Aboutthe 12 Mile Creek Site

In the last couple of decades there has been arenewed interest in 12 Mile Creek. Additional workat the site and with the museum collection wasdesigned to learn more about the site formationand to increase our confidence regarding a humanpresence (Frederickson 1961a, 1961b; Hill 1994,1996, 2002; Rogers 1984; Rogers and Martin 1984;Smith and Frederickson 1962). Although fieldwork at the site in the 1960s and 1990s was unableto identify the original excavation area, the studyof the curated faunal remains has been more pro-ductive (Hill 1996).

Three radiocarbon dates from the curatedbones yielded estimates of 10,435±260 (GX-5812A, bone apatite) and 10,245±335 (GX-5812,bone gelatin), and 10,520±70 (CAMS-16072,XAD-gelatin) B.P., which overlap at one standarddeviation (Hill 1996:361; Rogers and Martin1984). For the pooled mean 10,504±66 B.P., thepossible calibrated age ranges are 10,260–10,208cal B.C. (p = .03) and 10,787–10280 cal B.C. (p =.97) (Calibrated at 2 sigma with the programCALIB 5.0.1 [Stuiver and Reimer 1993] using thecalibration dataset INTCAL04.14C [Reimer et al2004]).

Recent work has also identified indisputableevidence for human butchery of at least two of thebison from 12 Mile Creek. Rogers and Martin(1984:759–760) identified a series of cut markson the ventral side of an atlas and on the proximalend of an ulna. In a separate study, I was able toconfirm Rogers and Martin’s findings, and identi-

fied additional cut marks on two tibias, two meta-carpals, an innominate fragment, and one calca-neus (Hill 1994, 1996). Macroscopically, the butch-ery marks are short, deep, v-shaped incisions. Un-like the modern cut marks produced by excava-tion and museum preparation activities, the pre-historic marks are identical in color to the rest ofthe exterior surfaces of the bones, indicating thatthey are of a similar antiquity (Lyman 1994).

The placement of most of these cut marks sug-gests that butchery was designed to dismember thecarcasses and remove the hides (Hill 1996). Butch-ery marks on the proximal ulna, cranial surface ofthe calcaneus, and ventral side of the atlas are in-dicative of the severing of muscles or tendons attheir place of attachment. Cut marks around theacetabulum represent separation of the femur fromthe pelvis. Butchery marks on the distal end of themetacarpals were probably created during the re-moval of the hide. Indications for filleting of meatcome from cut marks on the proximal shaft of thetibia. This evidence, in conjunction with the pres-ence of the projectile point, support the inferencethat Paleoindian hunters butchered and killed the12 Mile Creek bison.

A detailed taphonomic study of the faunal as-semblage (Hill 1994, 1996, 2002) suggests that 13bison are present at the site and represent a smallgroup of animals that probably died during the latewinter or early spring. There is evidence for highskeletal completeness among the carcasses withalmost no evidence for carnivore gnawing, sub-aerial weathering, density-mediated destruction, orfluvial sorting.

INITIAL REACTIONSTO 12 MILE CREEK

American paleontologists were among thefirst, and perhaps strongest, supporters of the im-portance and antiquity of 12 Mile Creek. Their in-terest, not surprisingly, focused primarily on thebison remains (Hay 1914, 1918; Lucas 1899;Osborn 1910). The 12 Mile Creek remains wereinitially identified as Bison antiquus (Stewart 1897;Williston 1897), but later F.A. Lucas (1899) of theU.S. National Museum (Smithsonian Institution)identified them as Bison occidentalis (see also Lane1948; Martin 1990). This collection of bison re-mains was so important that in the early part of the

5

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

century 12 Mile Creek was treated as if it was thetype locality of this species (Rogers and Martin1984). In fact, the paleontologist Arthur Smith-Woodward obtained a number of bone specimensfrom the site to place in the British Museum’s col-lection of Pleistocene fauna (A.S. Smith-Wood-ward to H. T. Martin, letter, 5 April 1923, HandelT. Martin Papers, University of Kansas Museumof Natural History, Lawrence [HTM/KUMNH]).

Paleontological interest in the site was not lim-ited to the bones, for the significance of the asso-ciated projectile point was immediately recognized.Alban Stewart (1897:129), one of Williston’s stu-dents, stated that the 12 Mile Creek bison were“cotemporary with the Mammoth, Mastodon, andwith man, as a small but well fashioned arrow-headwas found by H.T. Martin.” In his review of Pleis-tocene fauna in North America, paleontologistHenry Fairfield Osborn (1910:463) referred to 12Mile Creek site as “the richest deposit of the Pleis-tocene of Kansas.” Later in that same volume heclaims that 12 Mile Creek is “[t]he most importantcase of association of an arrowhead with an ex-tinct species of bison” (Osborn 1910:497).

In 1916, Oliver P. Hay, then of the CarnegieInstitute, and E.H. Sellards, then State Geologistof Florida, became interested in the 12 Mile Creeksite. In a letter to Martin, Sellards stated, “You maybe sure that I have not forgotten the fact that youfound an arrowpoint underneath the scapula of abison nor have I questioned the authenticity of thefind” (E. H. Sellards to H. T. Martin, letter, 29November 1916, HTM/KUMNH). But even astrong supporter such as Sellards recognized thatthere were some critics who would not accept thevalidity of 12 Mile Creek: “But you know fromyour own experience that when a fellow under-takes to establish the presence of man in the Pleis-tocene he has his hands full and it seemed to bebest in these first papers to stick strictly to the oneproblem, and not bring in those [sites] which hadpreviously been reported and not universally ac-cepted” (E. H. Sellards to H. T. Martin, letter, 29November 1916, HTM/KUMNH).

That same year, Hay (1918:23–24) cites 12Mile Creek along with a series of other localities(many very dubious) as evidence for the associa-tion of human artifacts with Pleistocene fauna. Asmall number of anthropologists and archaeolo-

gists were early to recognize the importance of thesite. Thomas Wilson, conservator of prehistoricarchaeology at the National Museum, published ashort summary of the site and a drawing of theprojectile point in 1901. He wrote that the projec-tile point “qui avait été sans nul doute déposée encet androit avant la mort de l’animal [which with-out a doubt was deposited in this place before thedeath of the animal]” (Wilson 1901:305). Althoughhe mistakenly reported the site was located inWyoming, Wilson clearly believed that the pointfrom the site was directly associated with Pleis-tocene fauna.

In 1923, as part of Fossil Men: Elements ofHuman Palaeontology, the French human paleon-tologist Marcellin Boule (1923) summarized muchof the available evidence for the earliest peoplingof North America. Boule certainly was very cau-tious in his support for any claim of great antiq-uity: “it is difficult for an outsider to take a firmstand one side or the other, for he can only exer-cise his judgment on facts collated by others”(Boule 1923:411). However, he did acknowledgethat at least some claims, 12 Mile Creek amongthem, could not be disputed in demonstrating thedirect association of human artifacts with Pleis-tocene fauna (Boule 1923: 400–401). Decades laterBoule was to change his opinion about the site (seeBoule and Vallois 1957:472).

The small group of scholars who accepted theage of the site during this period — e.g., Hay,Sellards, Osborn, Wilson — were already strongsupporters of an early human presence in theAmericas. And although there is no reason to ques-tion these researchers’ acceptance of the evidencefrom 12 Mile Creek, their support is also not en-tirely persuasive. At the time of the 12 Mile Creekdiscovery these same researchers were vigorouslysupporting other — and sometimes suspect — earlyfinds. For example, Wilson (1889, 1896, 1901) wasa long time vocal supporter of American Paleolithicfinds throughout the United States. Both Hay andSellards’ interest in 12 Mile Creek were drawnwhile investigating reports of Pleistocene-age hu-man remains found near Vero Beach, Florida(Sellards 1916a, 1917a; Hay 1918). Finally, Osborn(1907, 1910) also supported the antiquity of theskeletal remains from Gilder Mound as well asother associations of human artifacts with Pleis-

6

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

tocene fauna. A cynic could view support of 12Mile Creek by these researchers as an attempt tovalidate their own discoveries of reportedly greatantiquity.

12 MILE CREEK ANDTHE FOLSOM DISCOVERY

The discoveries at Lone Wolf Creek, Texas(Cook 1925, 1926, 1927) and Folsom, New Mexico(Brown 1928; Cook 1927, 1928; Figgins 1927)changed much in North American archaeology.Obviously, these sites stimulated a wide interest inthe history of human occupation in the New World(Kidder 1936; Roberts 1940; Wilmsen 1965), butthey also drew attention back to 12 Mile Creek.The principal investigators of the Lone Wolf Creekand Folsom sites, Barnum Brown, Jesse D. Figgins,and Harold J. Cook, viewed their work as substan-tiating a number of earlier finds, including 12 MileCreek (Jackson and Thacker 1992).

Barnum Brown appears to have been the firstto recognize the similarities between 12 Mile Creekand Folsom and Lone Wolf Creek. He later activelyencouraged Figgins’ and Cook’s investigation ofFolsom because he thought these later discoveriesvalidated Williston’s claims about the age and im-portance of 12 Mile Creek. Brown’s support of thesite is not surprising as he was Williston’s studentat the time of Martin’s fieldwork. The earliestrecord of Brown’s championing of 12 Mile Creekoccurred in 1925, soon after the discovery of LoneWolf Creek. Immediately after the site’s discov-ery, Brown wrote to Martin to obtain photographsof the mounted bison skeleton and casts of the pro-jectile point from 12 Mile Creek. In this letter, hestated, “it is time more recognition was given tothe occurrence of the point and skeleton” (B.Brown to H. T. Martin, letter, 11 September 1925,HTM/KUMNH). Days later, in a telegram toFiggins soliciting a paper about Lone Wolf Creekfor Natural History, Brown suggests “Illustrationsfor Kansas specimen can be secured here STOPWould make comparison [with 12 Mile Creek] ifyou have not already done so” (B. Brown to J. D.Figgins, letter, 25 September 1925, Barnum BrownPapers, American Museum of Natural History, NewYork [BB/AMNH]).

When work began at the Folsom site a yearlater, Brown continued to stress the significance

of 12 Mile Creek to Figgins: “I think it is mostdesirable also that you should include the illustra-tion of the bison with the arrowpoint in the KansasState Museum” (B. Brown to J. D. Figgins, letter,30 November 1926, JDF/CMNH). Likely in re-sponse to Brown’s prompting, Cook eventuallyapproached Martin to gain more information abouthis earlier work. In December of 1925 Cook wroteto Martin, “will it be possible to get a good photoof your bison and the arrowpoint you have there?I’d like to compare these with the Texas [Lone WolfCreek] find” (H. J. Cook to H. T. Martin, letter, 15December 1925, HTM/KUMNH). Figgins saw thevalue in comparing Folsom to 12 Mile Creek. Ashe wrote to Martin:

I am preparing an article for Natural History [seeFiggins 1927], dealing with our finds of artifacts,associated with fossil Bison, in Texas and NewMexico, and Mr. Barnum Brown is anxious that Iinclude details regarding Dr. Williston’s find, of alike nature in Kansas. As I view our discoveries inthe light of verifications of the Kansas finds, I amanxious that it should be included....Mr. Brown ex-amined the artifact, in your museum, and tells me itis very closely similar to our Texas examples (em-phasis added, J. D. Figgins to H. T. Martin, letter,16 December 1926, JDF/CMNH).

A few weeks later, Figgins again reiterated toMartin his belief in the similarities between thetwo sites, “I am convinced that our finds [Folsomand Lone Wolf Creek] are going to substantiateyours, and I hope, hush the opposition that has hith-erto been raised by a small group of archaeolo-gists [i.e., Holmes and Hrdlicka]. If not look for areply to anything they may have to say. It will beworth reading” (J. D. Figgins to H. T. Martin, let-ter, 8 January 1927, JDF/CMNH).

Just 10 days after Figgins sent out the famoustelegrams requesting that researchers come toFolsom and evaluate the site for themselves,Figgins wrote to Martin “everyone was delightedthat our arrowheads from Texas [Lone Wolf Creek]verified the importance of your find in Kansas” (J.D. Figgins to H. T. Martin, letter, 10 September1927, KTM/KUMNH).

These researchers did not limit their supportfor 12 Mile Creek to personal communications.There were also references to 12 Mile Creek in theearly publications on Folsom and Lone Wolf Creek.For example, while suggesting that the projectile

7

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

points from Lone Wolf Creek represent a new andearly cultural stage, Figgins (1927:231–232) em-phasized the similarities of these artifacts to thepoint from 12 Mile Creek. Renaud (1928) includedan extended discussion of 12 Mile Creek in anoverview of the Frederick, Lone Wolf Creek,Folsom, and Agate Springs sites.

The above evidence indicates that although 12Mile Creek had been known for 32 years, it tookon new significance in light of the work at Folsom.Its appearance in published articles on Folsom andLone Wolf Creeks suggests that the authors agreedthe site was an important find. Of course, it largelyassumed this newly found importance due to Cook,Figgins, and Renaud’s need to bolster their argu-ment for their new site. References to 12 MileCreek in the early papers on Folsom and Lone WolfCreek are made to show that they were not uniqueand that early finds had already been made. In fact,Renaud (1928:33) openly admits that by itself, 12Mile Creek could not convince critics of a longoccupation in the Americas; however, by combin-ing the evidence from 12 Mile, Folsom, Lone WolfCreek, and Frederick, the evidence for such anoccupation was irrefutable.

It must be recognized that the support byFiggins and Cook cannot be viewed as universalacceptance of 12 Mile Creek in the larger researchcommunity. These same researchers also vigor-ously argued for an early cultural presence atFredericks, which was quickly rejected by most ofthe scientific community (Meltzer 1983, 1994).Moreover, Cook (1927, 1928), for example, sug-gested that sites such at 12 Mile Creek, Lone WolfCreek and Folsom were far older than we currentlyaccept today.

REACTIONS AFTER FOLSOMThere was a rapid succession of new site dis-

coveries in the decades following the work atFolsom (Barbour and Schultz 1932; Davis 1953,Figgins 1933; Holder and Wike 1949; Howard1935; Moss 1951; Roberts 1935; Schultz andEiseley 1932, 1935, 1943; Sellards 1938). Discus-sion of 12 Mile Creek within this early Paleoindianliterature was generally limited. Although a smallnumber of archaeologists and other researchersacknowledged the historical importance of 12 MileCreek, at this time it played almost no role in the

growth and development of Paleoindian archaeol-ogy.

This period was also marked by the first timea researcher openly questioned the age and sig-nificance of the site (e.g., Romer’s [1933] claimthat site did not date to the Pleistocene). The 12Mile Creek site was largely ignored by some re-searchers before the Folsom discovery, but it hadnever been openly rejected. The argument ad-vanced to question the age of 12 Mile Creek ap-plied equally to the Folsom discovery, demonstrat-ing that there was a group of investigators whowere clearly not convinced by the Folsom evidence(see discussions in Rogers and Martin 1986, 1987;Wilmsen 1965).

Not surprisingly, Figgins (1933) made the firstreference to the 12 Mile Creek site after the Folsomdiscovery in his Dent site report. He lists 12 MileCreek along with Folsom, Lone Wolf Creek,Scottsbluff, and Merserve as sites where there isunquestionable association between human arti-facts and extinct fauna (Figgins 1933:7–8). A fewyears later, Schultz and Eisley (1935:311–312)pointed to 12 Mile Creek as proof that B.occidentalis was an extinct Pleistocene species.

E. H. Sellards (1940, 1947, 1952) kept 12 MileCreek visible in the archaeological literaturethrough the 1940s and early 1950s by publishingdescriptions of all known Paleoindian sites in theAmericas. His renewed interest in 12 Mile Creekappeared to be tied to his work at the Plainviewsite. At this time Sellards wrote to Claude Hibbard,Martin’s replacement as curator at the Universityof Kansas, “I am presenting a paper at Pittsburghon a new find of bison bones with artifacts [fromthe Plainview site], and want to refer to Martin’sfind” (E. H. Sellards to C. W. Hibbard, letter, 13November 1945, CWH/KUMNH). In the pub-lished account only passing reference is made to12 Mile Creek (Sellards et al. 1947). However, incontemporary letters, Sellards clearly expresses hisview that 12 Mile Creek was the first instance inwhich human artifacts were recovered in directassociation with Pleistocene fauna (E. H. Sellardsto C. W. Hibbard, letter, 8 March 1946, CWH/KUMNH; Sellards 1952).

Waldo Wedel (1959:88; see also Wedel 1982)makes a similar claim in his Introduction to Kan-sas Archaeology: “so far as I know, the circum-

8

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

stances of this find have never been questioned,and the association is apparently accepted by pa-leontologists qualified to judge the merits of thecase.” Wedel (1959:89) continues “here [at 12 MileCreek], as elsewhere in America at that time, I sup-pose there would have been no question about thePleistocene dating of the site had there not beenevidence of human association.” This latter state-ment by Wedel, which mirrors similar commentsby earlier researchers (i.e., Kidder 1936:143–144),demonstrates that during this period it was increas-ingly recognized that some early researchers (e.g.,Holmes and Hrdlicka) were likely too quick to dis-miss or ignore some evidence, such as 12 MileCreek, for a Pleistocene presence in North America.

As stated above, it was during this time thatsmall number of researchers first raised questionsabout the significance of the 12 Mile Creek evi-dence. The chief critic was Alfred S. Romer, pale-ontologist at the University of Chicago. He arguedthat 12 Mile Creek, as well as Lone Wolf Creekand Folsom, did not date to the Pleistocene butinstead was likely much more recent in age. Thisstatement was based on the reasonable belief thatso little was known about these early bison spe-cies (i.e., B. occidentalis and B. antiquus) that therewas no certainty in using them as a basis for as-signing an age to the associated deposit. Specifi-cally, he argues:

These finds certainly show association of Manwith extinct forms. Other than this, positive state-ments are difficult....It is clear, therefore, that posi-tive statements cannot be made on faunal evidenceas to possible date of the occurrence. At least one ortwo extinct species of bison are known to have sur-vived the Wisconsin glaciation. It is probable thatall these finds may be of post-Wisconsin date; thereis no necessity of implying any great geologicalantiquity to them (Romer 1933:80).

This same line of reasoning was picked up byKroeber (1940:475), who suggested that it waspossible that some of the presumed extinct fauna,such as bison and mammoths, may have “lingeredon into the various phases of the Recent, some forperhaps two thousand years, others for five thou-sand, a few possibly for eight thousand.” Althoughseveral researchers were quick to counter such asuggestion (Eiseley 1943; Schultz and Eiseley1935), it is evident that even after the Folsom dis-covery there was significant skepticism about the

antiquity of sites such as 12 Mile Creek andFolsom. Doubt about the absolute age of thesetypes of sites could not be eliminated until the de-velopment of radiocarbon dating (Jackson et al.1987; Rogers and Martin 1987; Wilmsen 1965),but most researchers accepted paleontological evi-dence, especially at Folsom, as reasonable evidencefor a great antiquity for human presence in theAmericas.

IGNORING THE SITEDespite the initial interest shown in 12 Mile

Creek following the appearance of the publicationson the site, by the end of the first quarter of thetwentieth century the site was apparently quicklyforgotten or at least ignored by researchers work-ing on the earliest occupation of North America.Interestingly, it was ignored in spite of the fact thatno contemporary researcher ever questioned thevalidity of Martin’s discovery or suggested an al-ternative explanation for the association of the ar-tifact and bison remains. The two chief archaeo-logical critics of the idea for an Ice Age occupa-tion of the New World, William Henry Holmes andAles Hrdlicka, never explicitly discussed 12 MileCreek in print (Holmes 1902, 1918, 1919, 1925;Hrdlicka 1907, 1918, 1926, 1928, 1942). The siteis also absent from important archaeological over-views about evidence for Pleistocene humans inNorth America in the first quarter of the century(Fewkes et al. 1912; Nelson 1918; Wissler 1916).Likewise, the site is entirely absent from the vo-ciferous debate over the later discoveries at Lan-sing, Kansas (Chamberlin 1902; Hrdlicka 1903;Upham 1902a, 1902b, Williston 1902b; Winchell1909; G.F. Wright 1903) and Vero, Florida (Hay1918; MacCurdy 1917; Sellards 1916a, 1916b,1917a, 1917b), as well as discussions on other dis-coveries of human artifacts associated with extinctfauna (F.B. Wright 1903), and the continued prob-lem of “Paleolithic” artifacts being recoveredacross North America (Winchell 1912).

It is assumed that Holmes, Hrdlicka, and oth-ers had direct knowledge of the site. Many of thekey players in the early peopling debate were par-ticipants in the 1902 International Congress ofAmericanists in New York, where Williston (1905)first presented information on the 12 Mile Creeksite. For example, Holmes presented a paper en-

9

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

titled “The Relation of the Glacial Period to thePeopling of America,” at the same conference,probably in the same session as Williston’s. Un-fortunately, Holmes’ paper was not included in thepublished proceedings of the conference, so it isnot known whether he discussed 12 Mile Creek atthat time. Around 1902, Williston took a job at theUniversity of Chicago and worked in the samedepartment as T. C. Chamberlain (Shor 1971), andpresumably at some point they would have dis-cussed 12 Mile Creek.

Holmes (1918:562) does make one very ob-lique reference to 12 Mile Creek. In 1918, he pub-lished a response to an American Anthropologistarticle written by Oliver P. Hay (1918). In this ar-ticle Hay discussed 12 Mile Creek along with ap-proximately 20 other sites as evidence for an IceAge occupation of North America. In response toHay’s article, Holmes (1918:562) stated:

Dr. Hay has published a map giving locations offinds of traces of man attributed to the Pleistocene,these in cases being associated more or less inti-mately with remains of Elephas imperator. But thisassociation is open to different interpretations and Ifeel justified in raising the danger signal in each andevery case since, if left alone, lamentable errors maybecome fixtures on the pages of history.

It is reasonable to assume that Holmes included12 Mile Creek in with these other sites, but no spe-cific criticisms were made.

In the absence of negative comments concern-ing the site, we must assume that Holmes, Hrdlicka,and others critics of an early occupation believedthat the case for 12 Mile Creek site was not worththeir time to refute. Likely it was considered yetanother instance of an equivocal association of anartifact with extinct fauna remains.

WHAT WAS DIFFERENTABOUT 12 MILE CREEK?

Why didn’t more researchers either recognizethe site as evidence of a Pleistocene occupation orattack the evidence for such a claim? Rogers andMartin (1986:44) suggest 12 Mile Creek is an ex-ample of what J.D. Figgins (1927:229) describedas “a failure to appreciate properly all the evidence,and a seeming unwillingness to accept the conclu-sions of authorities engaged in related branches ofinvestigation.” But this answer cannot explain whya number of contemporary and later researchers

did recognize the importance of the site. I evaluatehere the reasons why 12 Mile Creek did not havemuch of an effect on the archaeological commu-nity, compared to Folsom three decades later. Ingeneral, previous researchers point to two issues.Some argue that the loss of the projectile point fromthe curated collection of 12 Mile Creek causedpeople to ignore the site, while others suggest thatthe site was ignored because the original investi-gators never claimed it was very old. Each view-point will be discussed in turn.

The Lost PointRogers and Martin (1984, 1986, 1987; Rogers

1984) point to the loss of the projectile point asthe primary reason the archaeological communityfailed to grasp the significance of 12 Mile Creek.They argue that because the point was lost, therewas no way for outside researchers to evaluate theclaims of a cultural component to the site (a simi-lar argument was made by Howard 1935:145).

The obvious problem is that apparently mostoutside researchers did not know the point wasmissing until after the Folsom discovery. The origi-nal publications on the site never mentioned thatthe point was missing. Around the time of the LoneWolf Creek and Folsom excavations, a number ofresearchers requested photographs or casts of thepoint, presumably because they thought the pointstill existed (B. Brown to H. T. Martin, letter, 11September 1925, HTM/KUMNH; H. J. Cook toH. T. Martin, letter, 15 December 1925, HTM/KUMNH; J. D. Figgins to H. T. Martin, letter, 20December 1926, JDF/CMNH). Martin’s responseto some of these requests suggests that he wishedto hide the loss of the point from the larger com-munity. Writing to Figgins, Martin said “‘Now asecret’...The original was unfortunately lost — orto be more exact stolen by a party — just after ameeting at Dr. Williston’s house many years ago”(emphasis in original; H. T. Martin to J. D. Figgins,letter, 30 December 1926, JDF/CMNH). In fact,Martin went so far as to place another projectilepoint within a museum display created for 12 MileCreek site at the University of Kansas, apparently“to satisfy the gossip of a newspaper woman fromTopeka” (J. D. Figgins to H. T. Martin, letter, 30December 1926, JDF/CMNH). Information aboutthe loss of the point was so well guarded that

10

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

Martin’s replacement at the University of Kansas,Claude Hibbard, only found out about it just be-fore Martin died (C.W. Hibbard to J. D. Figgins,letter, 13 April 1942, CWH/KUMNH). Even afterfinding out the point was stolen, Brown, Cook,Figgins, and Sellards all continued to argue for theimportance of the site.

No Evidence of Great AntiquityA number of researchers (Meltzer 1991, 1994;

Rogers and Martin 1987; Wilmsen 1965) contendthat many archaeologists were reluctant to acceptthe antiquity of sites such 12 Mile Creek, LoneWolf Creek, Folsom, and Meserve because of “le-gitimate skepticism” of either problems with thecircumstances of excavations (e.g., non-profes-sional excavators) and/or the fact that the bisonremains and associated projectile points were “notunequivocal evidence” for a site being claimed todate to the Pleistocene (Meltzer 1991:33). AsMeltzer (1994:11) rightfully acknowledges, manyearly claims for sites of great antiquity wereplagued by these types of problems associated with“mere ‘relic hunters’ who ‘lacked adequate knowl-edge,’ had ‘preconceived notions,’ and practicedunscientific methods.” But 12 Mile Creek wasnever subjected to this type of criticism (Meltzer1991). Just like the Folsom site, this site was care-fully excavated by scientifically-trained research-ers under the direction of a renowned paleontolo-gist who was fully capable of interpreting the ageof the site.

Instead, Meltzer (1991:30) has argued that thesite never played an important role for the simplefact that “Williston himself never claimed greatantiquity for the site, since he was unsure of theage.” He went on to suggest, “The 12 Mile Creeksite never entered the debate over human antiquityfor the obvious reason that in 1902 bison still livedon the Plains and there was no evidence then toindicate that these particular bison remains or theassociated projectile points were late Pleistocenein age” (Meltzer 1991:30).

Based on our current understanding of the ageand bison paleontology at 12 Mile Creek, the siteunquestionably dates to the Pleistocene. However,Meltzer (1994:17) argues that at the time of thesite’s discovery, 12 Mile Creek was considered“just a bison kill, whose age was unknown” so why

should it have any influence on the larger scien-tific community. This argument is a continuationof the suggestions of Romer (1933:78) and others(Kroeber 1940; Hrdlicka 1942). Hrdlicka(1942:54) most clearly expresses this line of rea-soning: “The mainstay of all the claims for man’santiquity in America is the association of theFolsom points and a few other objects with thebones of extinct mammals. But this is an Achilles’heel of American archaeology, for many conditionsindicate that such animals have not been extinctvery long.”

This argument suggests that, only in retrospectand primarily due to the appearance of radiocar-bon dating, were sites like 12 Mile Creek andFolsom recognized as being of great antiquity(Rogers and Martin 1987; Wilmsen 1965). Whilea few researchers might have shared this view, itcertainly was not widely believed by most in thearchaeological or geological community and cer-tainly did not reflect the beliefs of Williston.

Williston unquestionably accepted that 12Mile Creek dated to the Pleistocene. Further, hefully appreciated the paramount importance of theassociation of the point with an extinct form ofbison. For example, Williston’s first published ref-erence to the site came when, in 1897, he publisheda list of Pleistocene species recovered from Kan-sas and placed Homo sapiens at the top of the listdue to Martin’s work at 12 Mile. His writings alsoclearly show that he believed that the 12 Mile Creekbison belonged to the Pleistocene-aged Equusfauna (Williston 1902a, 1902b, 1905). Williston(1897:301) stated, “the contemporeity of man withthe Equus fauna is, I think assured by the discov-ery of arrowheads associated with remains of Bosantiquus, in Gove [sic] county, by H. T. Martin.”In an article concerning the Lansing skeleton,Williston (1902b) is more specific about the ageof the Equus fauna — it “is evidently post-glacial[maximum], but nevertheless very great.” Finally,the clearest statement of Williston’s beliefs on thissubject comes in his review of Osborn’s (1910)The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia, and NorthAmerica, where he stated: “The writer is one whostill believes, notwithstanding the objections raisedby geologists and anthropologists, that there ispaleontological evidence of man’scontemporaneity in North America with some, at

11

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

least, of the extinct mammals” (Williston1910:251).

Of course, without radiocarbon datingWilliston was unable to provide a precise calendarage for the Pleistocene fauna. But the antiquity of12 Mile Creek was determined through cross-dat-ing the artifacts with the extinct bison. This wasthe same technique that later researchers used tosuccessfully argue for a Pleistocene age of siteslike Folsom, Blackwater Draw, Lindemeier, andGypsum Cave (Colbert 1942, Figgins 1927;Howard 1935; Roberts 1935, 1940; Schultz andEiseley 1935; Sellards 1947). At some of thesesites, detailed stratigraphic correlations were usedto confirm the estimated age (Bryan 1937, Moss1951), but in general all Paleoindian sites prior to1950 were argued to be of great antiquity based onthe presence of an extinct fauna just as was doneat 12 Mile Creek.

CONCLUSIONAs I have tried to outline above, from our

modern perspective 12 Mile Creek should haverepresented a reasonably compelling case for aPleistocene occupation of the Americas. At the site,an unquestionable artifact was found in direct as-sociation with an extinct form of bison. This formof bison was thought to date to the Pleistocene.Today, taphonomically-oriented archaeologistsmight wonder what was the actual association be-tween the point and the fossils. My previous workwith the collection suggests, at least to me, thatthere probably is no reason to question the asso-ciation. Perhaps more importantly, no one, at thetime of or following the site’s discovery, has everquestioned the association of the projectile pointwith the bison. In addition, at the time of the site’sdiscovery no one questioned the age of the fossils.True, after the acceptance of the age of the Folsomsite, a small group of researchers raised the possi-bility that these types of fossils were not diagnos-tic of Pleistocene deposits. But these criticismscame after the fact and were quickly refuted.

In addition, 12 Mile Creek was not only rec-ognized as significant in hindsight. The importantfacts about the site — the presence of the pointwith the bison remains — were appreciated by theprincipal investigators of the site and by a smallnumber of contemporary researchers. So why was

the site mostly ignored in the debate about the peo-pling of the Americas? I have already discussedwhy prior explanations are not very edifying. I willnow turn to consider a possible factor in why 12Mile Creek did not make a larger contribution tothis debate.

It is important to realize that the work at 12Mile Creek occurred during the beginning stagesof the intellectual development of archaeology.When researchers trying to argue for an early peo-pling of the New World did not have the tools tomake an argument that would satisfy a vocal critic.For example, when Martin went into the field in1895, there were no universally accepted guide-lines for collecting and disseminating archaeologi-cal data. In addition, at this time it was not estab-lished how other researchers were supposed toevaluate one’s inferences about the data.

In the late 1800s, a professionally trained ar-chaeological community did not really exist. Un-like at Folsom, the workers at 12 Mile Creek couldnot draw on a group of respected archaeologists tocorroborate the validity of their discoveries nor didit occur to them to do so. This circumstance was afunction of the infancy of higher education at thetime. The earliest educational institutions grantingPh.D.s in anthropology and archaeology (e.g.,Harvard in 1886; Chicago in 1892; Clark Univer-sity in 1892; Columbia in 1896, and Berkley in1901) had either not yet been founded or were lessthan 10 years old at the time of the 12 Mile Creekexcavations (Meltzer 1985; Willey and Sabloff1993). In 1895 there were very few academically-trained archaeologists and most people practicingarchaeology, including those at the Bureau ofAmerican Ethnology, were trained in other fieldsand were archaeologists only by avocation (Meltzer1985:249). In contrast, by the time of the Folsomexcavation there was a cadre of stellar university-trained archaeologists, such as Alfred V. Kidder,Nels Nelson, and Frank H.H. Roberts, that wereable to visit the site and had the skills to evaluatethe evidence for the association between the arti-facts and the fauna at Folsom.

This paucity of trained professionals alsomeant that there were no rigorous standards con-cerning fieldwork techniques and no system inplace to validate archaeological interpretations.These two components of a scientific archaeology,

12

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

while present by the 1920s and critical to the ac-ceptance of the Folsom evidence, were in theirembryonic form at the time of the 12 Mile Creekwork (Willey and Sabloff 1993:56). T.C.Chamberlain’s (1903) paper entitled “The CriteriaRequisite for the Reference of Relics to a GlacialAge” certainly represented an important step in thedirection of establishing such a professional re-search system. But it was just the beginning. An-other important component in thisprofessionalization process was the efforts of Wil-liam Henry Holmes and Ales Hrdlicka. Their in-sightful (and often vitriolic) criticism of claimsgreatly facilitated archaeology’s eventual accep-tance of the appropriate mode of data presentationand evidence validation (Meltzer 1983, 1985, 1991,1994; Willey and Sabloff 1993).

For vocal critics such as Holmes and Hrdlickato simply ignore the claims about 12 Mile Creeksite is understandable, considering the great num-ber of specious claims presented as proof for aPleistocene occupation of North America. Nelson(1933:100) argues that prior to the Folsom discov-ery the archaeological literature was awash in pur-ported claims (over 187 localities) for a very an-cient human antiquity in the New World. More-over, this estimate does not include approximately8500 supposed American Paleolithic finds reportedfrom the United States and Canada (Nelson1933:94). Compounding the problem of a highnumber of claims was that the published reportsfor most were so poor that it was almost impos-sible to evaluate their veracity. Howard (1935:145)noted “the difficulty lies in the fact that many ofthe earlier finds were reported upon in such a waythat many essential facts were passed over withlittle notice.” Wissler (1916:235) suggested theevidence for nearly all these sites was “character-ized by affidavits and sworn statements, as to theexact place, position, identity, etc. of the singleobjects found.”

Therefore, at the time of the 12 Mile Creekwork, while it was theoretically possible for a singleartifact found in undisturbed Pleistocene age de-posits to prove the existence of humans in NorthAmerica during the Pleistocene (i.e., Chamberlin1903:67; Wissler 1916:235), the reality was thatuntil Folsom, when multiple outside investigatorsmade first-hand observations of multiple artifacts

associated with multiple bison skeletons in an un-disturbed context, there was no instance wheresomeone other than the site’s primary proponentcould scientifically verify the discovery (Meltzer1983, 1991, 1994). Moreover, by the time of theFolsom discovery proponents such as Cook andFiggins could point to other site (i.e., 12 MileCreek, Lone Wolf Creek) where similar associa-tions between human artifacts and extinct faunahad been previously made.

Although convincing Holmes or Hrdlicka(e.g., Holmes 1925; Hrdlicka 1928, 1942) of verylong human history in North America would prob-ably have been a difficult task, other early research-ers (e.g., Nelson 1918:394; 1919:139; 1933:104)were eager to accept such claims as long as theycould be authenticated. Unfortunately, prior toFolsom the only evidence presented to authenti-cate a particular find was its own published report.The 12 Mile Creek site is a prime example of thisproblem. An interested researcher wanting proofof the association between the faunal remains andthe artifact could only rely on the word Martin andOverton. Williston (1902a:313) recognized thiswhen he stated, “While the evidence thus rests al-most exclusively upon the testimony of Messrs.Martin and Overton, I have not the slightest doubtof its reliability. I know from an intimate acquain-tance, that Mr. Martin is reliable, and I am confi-dent that the testimony of the two would be ac-cepted as conclusive in any court of justice.”

Unfortunately, the word of honorable men likeMartin and Overton was simply not adequate toresolve the controversy over the peopling of theNew World because too many apparently reliableclaims had been disproved or shown to be fraudu-lent. Had outside researchers been able to visit 12Mile Creek while the point was still in situ andconfirm the relationship between extinct bison andthe projectile point, as occurred later at Folsom,the history of North American archaeology wouldhave been different. This did not happen. So, eventhough a plausible argument for a Pleistocene oc-cupation at 12 Mile Creek could be made, the pre-sentation of such a claim was entirely unpersuasiveto skeptics. Therefore, there was no reason forskeptics such as Holmes and Hrdlicka to “debate”yet another personal testimonial.

The late 1800s was just not the right time for

13

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

the universal acceptance of a Pleistocene peoplingof Americas, because researchers did not under-stand how to present their evidence in a reliableand verifiable manner that would convince skep-tics. The Folsom discovery was different becausehow archaeology was done was different. Well-trained, respected outside investigators went toFolsom and were allowed to view artifacts in placeand to draw their own conclusions about the rela-tionship between the artifacts and faunal remains.Moreover, researchers from the American Museumwere able to carry out their excavations, and there-fore were able to independently verify prior find-ings (for examples of Figgins encouraging othersto carry out separate investigations at Folsom seeJ. D. Figgins to H.F. Osborn, letter, 12 September1927, BB/AMNH; J. D. Figgins to W. Granger,letter, 30 September 1927, BB/AMNH). In orderfor the archaeological community to recognize thesignificance of the Folsom site, it required not apersonal testimonial but visits from outside to thesite. This is what made Folsom different from ev-erything that came before it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis paper was inspired from extended discussions with LarryMartin about the 12 Mile Creek and its role (or rather the lackthere of) in the history of North American archaeology. Thepersonal communications used in this paper were obtained fromthe archives at the University of Kansas Library, University ofKansas Museum of Natural History, American Museum ofNatural History, and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.I would like to thank the staff of those facilities for providingaccess to their collection and their assistance during my visits,especially John Alexander (American Museum of NaturalHistory), Larry Martin (University of Kansas Museum ofNatural History) and Logan Ivy (Denver Museum of Natureand Science). Jason LaBelle kindly supplied copies of thecorrespondence from the archive of Denver Museum of Natureand Science. Tina Bothe and family are thanked for theirhospitality during my visit to New York. I thank LawrenceJackson, Larry Martin, and Susana Katz for their review of thispaper. The current paper also benefited from comments by JesseBallenger, Margaret Beck, Brandon Gabler, Janet Griffith, VanceHolliday, Brian McKee, David Meltzer, William Reitze, ChrisRoos, and Michael Schiffer. Although not everyone agreed withthe view presented here, their input greatly improved the contentand presentation.

REFERENCES CITEDBarbour, Erwin H., and C. Bertrand Schultz

1932 The Scottsbluff Bison Quarry and Its Artifacts. NebraskaState Museum Bulletin No 34. Nebraska State Museum,Lincoln.

Boule, Marcellin1923 Fossil Men: Elements of Human Palaeontology. Oliver

and Boyd, Edinburgh.Boule, Marcellin and Henri V. Vallois

1957 Fossil Men. The Bryden Press, New York.Brown, Barnum

1928 Discussion: Recent Finds Relating to Prehistoric Manin America. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medi-cine 4:824–828. Albany.

Brown, Kenneth L. and Brad Logan1987 The Distribution of Paleoindian Sites in Kansas. In

Quaternary Environments of Kansas, edited by WilliamC. Johnson, pp. 189–195. Kansas Geological SurveyGuidebook Series 5, Kansas Geological Society,Lawrence.

Bryan, Kirk1937 Geology of the Folsom Deposit in New Mexico and

Colorado. In Early Man, edited by George G. MacCurdy,pp. 139–152. J.B. Loppincott, Philadelphia.

Chamberlin, Thomas C.1902 The Geologic Relations of the Human Relics of Lan-

sing, Kansas. Journal of Geology 10:745–779.1903 The Criteria Requisite for the Reference of Relics to a

Glacial Age. Journal of Geology 11:64–85.Colbert, Edwin H.

1942 The Association of Man with Extinct Mammals in theWestern Hemisphere. Proceedings of the Eighth Ameri-can Scientific Congress 2:17–29. Washington, D.C.

Cook, Harold J.1925 Definite Evidence of Human Artifacts in the American

Pleistocene. Science 62:459–460.1926 The Antiquity of Man in America. Scientific American

135:334–336.1927 New Geological and Palaeontological Evidence Bear-

ing on the Antiquity of Mankind in America. Natural His-tory 27:240–247.

1928 Glacial Age Man in New Mexico. Scientific American139:38–40.

Davis, E. Mott1953 Recent Data from Two Paleoindian Sites on Medicine

Creek, Nebraska. American Antiquity 18:380–386.Eiseley, Loren C.

1943 Archaeological Observations on the Problem of Post-Glacial Extinction. American Antiquity 8:209–217.

Fewkes, Jesse W., Ales Hrdlicka, William H. Dall, James W.Gidley, Austin H. Clark, William H. Holmes, Alice C.Fletcher, Walter Hough, Stanbury Hager, Paul Bartsch,Alexander F. Chamberlain, and Roland B. Dixon.

1912 The Problem of the Unity or Plurality and the ProbablePlace of Origin of the American Aborigines. AmericanAnthropologist 14:1–59.

Figgins, Jesse D.1927 The Antiquity of Man in America. Natural History

27:229–239.1933 A Further Contribution to the Antiquity of Man in

America. Proceedings of the Colorado Museum of Natu-ral History 12:4–11. Denver.

Fredericksen, Walter M.1961a An Outline of the Results of the University of Kansas

Archaeological Field Survey to Logan County, Kansas,May 1961. Manuscript on file, University of Kansas

14

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

Museum of Anthropology, Lawrence.1961b May, 1961 Field Survey to Logan County, Kansas.

Field notes on file, University of Kansas Museum of An-thropology, Lawrence.

Hay, Oliver P.1914 The Pleistocene Mammals of Iowa. The 1912 Annual

Report of the Iowa Geological Survey. The State of Iowa,Des Moines.

1918 Further Consideration of the Occurrence of HumanRemains in the Pleistocene Deposits at Vero, Florida.American Anthropologist 20:1–36.

Haynes, C. Vance1993 Clovis-Folsom Geochronology and Climate Change.

In From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic-Paleo-In-dian Adaptations, edited by Olga Soffer and N.D. Praslow,pp. 219–236. Plenum Press, New York.

Hill Jr., Matthew E.1994 Paleoindian Archaeology and Taphonomy of the 12-

Mile Creek Site in Western Kansas. Unpublished Master’sthesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Kan-sas, Lawrence.

1996 The Paleoindian Bison Fauna from the 12-Mile CreekSite in Western Kansas. Plains Anthropologist 41:359–372.

2002 The Folsom-age 12 Mile Creek Bison Bonebed inWestern Kansas. In Institute for Tertiary-Quaternary Stud-ies-TerQua Symposium Series, Volume 3, edited byWakefield Dort, Jr., pp. 53–70. University of Kansas,Lawrence.

Hofman, Jack L.1994 Kansas Folsom Evidence. The Kansas Anthropologist

15:31–43.Hofman, Jack L. and Russell W. Graham

1998 The Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Great Plains. In Ar-chaeology on the Great Plains, edited by W. RaymondWood, pp. 87–139, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence.

Holder, Preston and Joyce Wike1949 The Frontier Culture Complex: A Preliminary Report

of the Prehistoric Hunters Camp in Southwestern Ne-braska. American Antiquity 14:260–266.

Holmes, William H.1902 Flint Implements and Fossil Remains from a Sulphur

Spring at Afton, Indian Territory. American Anthropolo-gist 4:108–129.

1918 On the Antiquity of Man in America. Science 47:561–562.

1919 Handbook of Aboriginal American Antiquities, Part 1Introductory the Lithic Industries. Bureau of AmericanEthnology Bulletin 60. Smithsonian Institution, Washing-ton D.C.

1925 The Antiquity Phantom in American Archeology. Sci-ence 62:256–258.

Howard, Edgar B.1935 Evidence of Early Man in North America, Based on

Geological and Archaeological Work in New Mexico. TheUniversity of Pennsylvania Museum Journal 24:55–171.

Hrdlicka, Ales1903 The Lansing Skeleton. American Anthropologist 5:323–

330.

1907 Skeletal Remains Suggesting or Attributed to EarlyMan. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 33.Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

1918 Recent Discoveries Attributed to Early Man in America.Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 66. SmithsonianInstitution, Washington D.C.

1926 The Race and Antiquity of the American Indian. Scien-tific American 134:7–9.

1928 The Origin and Antiquity of Man in America. Bulletinof the New York Academy of Medicine 4:802–816. Albany.

1942 The Problem of Man’s Antiquity in America. Proceed-ings of the Eighth American Scientific Congress 2:53–55.Washington, D.C.

Jackson, Lawrence J., Heather McKillop, and Susan Wurtzburg1987 The Forgotten Beginning of Canadian Palaeo-Indian

Studies, 1933–1935. Ontario Archaeology 47:5–18Jackson, Lawrence J., and Paul T. Thacker

1992 Harold J. Cook and Jesse D. Figgins: A New Perspec-tive on the Folsom Discovery. In Rediscovering our Past:Essays on the History of American Archaeology, editedby Jonathan E. Reyman, pp. 217–240. Worldwide Ar-chaeological Series 2. Avebury, Brookfield.

Kidder, Alfred V.1936 Speculations on New World Prehistory. In Essays in

Anthropology Presented to A. L. Kroeber in Celebrationof his Sixtieth Birthday, June 11, 1936, edited by RobertH. Lowie, pp. 143–152. University of California Press,Berkley.

Kohl, Michael F., Larry D. Martin, and Paul Brinkman (edi-tors)

2004 A Triceratops Hunt in Pioneer Wyoming: The Journalsof Barnum Brown and J.P. Sams: The University of Kan-sas Expedition of 1895. High Plains Press, Glendo, Wyo-ming.

Koeber, Alfred L.1940 Conclusions: The Present Status of Americanistic Prob-

lems. In The Maya and Their Neighbors, edited byClarence L. Hay, Ralph L. Linton, Samuel K. Lothrop,Harry L. Shapiro, and George C. Vaillant, pp. 460–489.D. Appleton-Century Company Inc., New York.

Lane, Henry H.1948 Survey of the Fossil Vertebrates from Kansas: Part V:

Mammalia. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Sci-ence Volume 51. Lawrence.

Lucas, Frederic A.1899 The Characters of Bison occidentalis, the Fossil Bison

of Kansas and Alaska. Kansas University Quarterly 3:17–20.

Lyman, R. Lee1994 Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.MacCurdy, George G.

1917 The Problem of Man’s Antiquity at Vero, Florida. Ameri-can Anthropologist 19:252–261.

Martin, Thomas1990 Jungpleistozäne und Holzäne Skelettfunde von Bos

primigenius und Bison priscus aus Deutchland un ihreBedeutung für die Zuordnung Isolierter Landknochen.Eiszeitalter u Gegenwart 40:1–19.

15

Matthew E. Hill, Jr. The 12 Mile Creek Site

McClung, Clarence E.1908 Restoration of the Skeleton of Bison Occidentalis.

Kansas University Science Bulletin 9:249–252.Meltzer, David J.

1983 The Antiquity of Man and the Development of Ameri-can Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Method andTheory 6:1–51.

1985 North American Archaeology and Archaeologists,1870–1934. American Antiquity 50:249–260.

1991 On “Paradigms” and “Paradigm Bias” in Controver-sies Over Human Antiquity in America. In The FirstAmericans: Search and Research, edited by Thomas D.Dillehay and David J. Meltzer, pp. 13–49. CRC Press,Boca Raton.

1994 The Discovery of Deep Time: A History of Views onthe Peopling of the Americas. In Method and Theory forInvestigating the Peopling of the Americas, edited byRobson Bonnichsen and D. Gentry Steele, pp. 7–25. Peo-pling of the Americas Publications, Corvallis.

Moss, John H.1951 Early Man in the Eden Valley. The University of Penn-

sylvania University Museum, Philadelphia.Nelson, Nels C.

1918 Review of Additional Studies in the Pleistocene at Vero,Florida, Pages 17–82, 141–143, from the Ninth AnnualReport of the Florida State Geological Survey. Science47:394–395.

1919 Human Culture: Its Probable Place of Origin on theEarth and Its Mode of Distribution. Natural History24:131–140.

1933 The Antiquity of Man in America in the Light of Ar-chaeology. In American Aborigines: Their Origins andAntiquity, edited by Diamond Jenness, pp. 87–130. TheUniversity of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Osborn, Henry F.1907 Discovery of a Supposed Primitive Race in Nebraska.

Century Magazine 73:371–375.1910 The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia, and North

America. The Macmillan Company, New York.Reimer, Paula J., Mike G.L. Baillie, Edouard Bard, Alex Bayliss,

J Warren Beck, Chanda J.H. Bertrand, Paul G. Blackwell,Caitlin E. Buck, George S. Burr, Kirsten B. Cutler, PaulE. Damon, R Lawrence Edwards, Richard G. Fairbanks,Michael Friedrich, Thomas P. Guilderson, Alan G. Hogg,Konrad A. Hughen, Bernard Kromer, Gerry McCormac,Stuart Manning, Christopher B. Ramsey, Ron W. Reimer,Sabine Remmele, John R. Southon, Minze Stuiver, SahraTalamo, F.W. Taylor, Johannes van der Plicht, andConstanze E. Weyhenmeyer,

2004 IntCal04 Terrestrial Radiocarbon Age Calibration, 0–26 Cal Kyr BP. Radiocarbon 46:1029–1058.

Renaud, Etienne B.1928 L’Antiquité de L’Homme dans L’Amérique du Nord.

L’Anthropologie 38:23–49.Roberts, Frank H.H.

1935 A Folsom Complex: A Preliminary Report on Investi-gations at the Lindenmeier in Northern Colorado.Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 94:1–35.

1940 Pre-pottery Horizons of the Anasazi and Mexico. InThe Maya and Their Neighbors, edited by Clarence L.

Hay, Ralph L. Linton, Samuel K. Lothrop, Harry L.Shapiro, and George C. Vaillant, pp. 331–340. D.Appleton-Century Company Inc., New York.

Rogers, Richard A.1984 Kansas Prehistory: An Alluvial Geomorphological Per-

spective. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department ofAnthropology, University of Kansas, Lawrence.

Rogers, Richard A. and Lawrence D. Martin1984 The 12 Mile Creek Site: A Reinvestigation. American

Antiquity 49:757–764.1985 Paleoindian Studies and Disappearance of Collected

Material. Current Research in the Pleistocene 2:59–60.1986 Replication and History of Paleoindian Studies. Cur-

rent Research in the Pleistocene 3:43–44.1987 Folsom Discovery and the Concept of Breakthrough

Sites in Paleoindian Studies. Current Research in the Pleis-tocene 4:81–82.

Romer, Alfred S.1933 Pleistocene Vertebrates and their Bearing on the Prob-

lem of Human Antiquity in North America. In AmericanAborigines: Their Origins and Antiquity, edited by Dia-mond Jenness, pp. 47–84. The University of Toronto Press,Toronto.

Schultz, C. Bertrand and Loren Eiseley1932 Association of Artifacts and Extinct Mammals in Ne-

braska, Nebraska State Museum, Bulletin 1:271–282.1935 Paleontological Evidence for the Antiquity of the

Scottsbluff Bison Quarry and Its Associated Artifacts.American Anthropologist 37:306–319.

1943 Some Artifact Sites of Early Man in the Great Plainsand Adjacent Areas. American Antiquity 8:242–249.

Sellards, Elias H.1916a On the Discovery of Fossil Human Remains in Florida

in Association with Extinct Vertebrates. American Jour-nal of Science 42:1–18.

1916b Human Remains from the Pleistocene of Florida. Sci-ence 44:615–617.

1917a On the Association of Human Remains and ExtinctVertebrates at Vero, Florida. Journal of Geology 25:4–24.

1917b Further Notes on Human Remains from Vero, Florida.American Anthropologist 19:239–251.

1938 Artifacts Associated with Fossil Elephant. Bulletin ofthe Geological Society of America 49:999–1010.

1940 Early Man in America Index to Localities and SelectedBibliography. Bulletin of the Geological Society ofAmerica 51:373–432.

1947 Early Man in America Index to Localities and SelectedBibliography, 1940–1945. Bulletin of the Geological So-ciety of America 58:955–978.

1952 Early Man in America: A Study in Prehistory. Univer-sity of Texas Press, Austin.

Sellards, Elias H., Glen L. Evans, and Grayson E. Meade1947 Fossil Bison and Associated Artifacts from Plainview,

Texas (with description of artifacts by Alex D. Krieger).Bulletin of Geological Society of America 58:927–954.

Shor, Elizabeth N.1971 Fossils and Flies: The Life of a Compleat Scientist.

University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

16

PLAINS ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 51, NO. 198, 2006

Smith, Carlyle S. and Walter M. Fredericksen1962 Field Work in Logan County, Kansas. Plains Anthro-

pologist 17:91–92.Stein, Martin

1984 Traces of Early Man in Kansas Tantalize Archeolo-gists. Kansas Preservation 6:5–7.

Stewart, Alban1897 Notes on Osteology of Bison Antiquus Leidy. Kansas

University Quarterly 6:127–135.Struiver, Minze and Paula J. Reimer

1993 Extended 14C Data Base and Revised Calib 3.0 14CCalibration Program. Radiocarbon 35:215–230.

Upham, Warren1902a The Fossil Man of Lansing, Kansas. Records of the

Past 1:273–275.1902b Man in the Ice Age at Lansing, Kansas and Little Falls,

Minnesota. American Geologist 30:135–150.Wedel, Waldo R.

1959 An Introduction to Kansas Archeology. Bureau ofAmerican Ethnology Bulletin 174. Smithsonian Institu-tion, Washington, D.C.

1982 Towards a History of Plains Archaeology. In Essays inthe History of Plains Archaeology, Reprints in Anthro-pology. J & L Reprints, Lincoln.

Willey, Gordon R. and Jeremy A. Sabloff1993 A History of American Archaeology. W.H. Freeman and

Company, New York.Williston, Samuel W.

1891 Kansas Mosausaurs. Science 19:345.1897 The Pleistocene. The University Geological Survey of

Kansas 2:299–308.1902a An Arrow-Head Found with Bones of Bison

Occidentalis Lucas, in Western Kansas. The AmericanGeologist 30:313–315.

1902b A Fossil Man from Kansas. Science 16:195–196.1903 On the Structure of the Plesiosaurian Skull. Science

17:9801905 On the Occurrence of an Arrow-Head with Bones of

an Extinct Bison. Proceedings of the International Con-gress of Americanist 13:335–337.

1910 Review of The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia, andNorth America, by Henry Fairfield Osborn. Science33:250–252.

Wilmsen, Edwin N.1965 An Outline of Early Man Studies in the United States.

American Antiquity 31:172–192.Wilson, M. Thomas

1889 The Paleolithic Period in the District of Columbia.American Anthropologist 2:235–241.

1896 Piney Branch (D.C.) Quarry Workshop and its Imple-ments. The American Naturalist 30:873–885.

1901 La Haute Ancienneté de l’Homme dans L’Amériquedu Nord. L’Anthropologie 12:297–339.

Winchell, Newton H.1909 The Age of the Lansing Skeleton. Records of the Past

8:139–140.1912 Paleolithic Artifacts from Kansas. Records of the Past

11:174–178.Wissler, C.

1916 The Present Status of the Antiquity of Man in NorthAmerica. The Scientific Monthly 2:234–238.

Wright, Frederick B.1903 The Mastodon and Mammoth Contemporary with Man.

Records of the Past 2:243–253.Wright, George F.

1903 The Age of the Lansing Skeleton. Records of the Past2:119–124.

Yaple, Dennis D.1968 Preliminary Research on the Paleo-Indian Occupation

of Kansas. Kansas Anthropological Association Newslet-ter 13:1–9.