Deconstructing "Chappelle's Show": Race, Masculinity,and ...

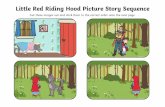

BA Dissertation on Children's Cultures: Deconstructing Little Red Riding Hood

Transcript of BA Dissertation on Children's Cultures: Deconstructing Little Red Riding Hood

Children’s Cultures

MD3408

Special Studies

Student’s Name: Alexia Kasparian

Student’s ID Number: K07237189

Tutor’s Name: Ewan Kirkland

1

Deadline For Submission: 16/01/09

Contents Page

1. Introduction…………………………….Page:.4-5

2. How Fairy Tales Have Been Used to Shape Society and What the Authors of Little Red Riding Hood Have To Say………………………………………….Page:6-7

3. The Film’s Continuous Motifs,

Metaphors & Symbols…………………………………….Page:8-14

2

4.The Dominance Of Story-Telling in the

Company of Wolves………………………………………Page:15-

20

5. Conclusion………………………….Page: 21

6. Bibliography…………………………Page: 22-23

List of Figures

1. ‘‘Rosaleen’’. From The Company of

Wolves, by Angela Carter (1984)………………………………

Page: 11

3

2. ‘‘Baby Figurines’’. From The Company

of Wolves, by Angela Carter (1984)

……………………………Page: 12

3. ‘Courtesy of the Canon Group’. From

The Company of Wolves, by Angela Carter

(1984) ………………………………………Page: 17

4

Critical Analysis of the use of the

Dream Framework of the film a Company of

Wolves , and How This Structure Explores

Dominant Ideologies of, Sexuality,

Femininity, and the Loss of Childhood

Innocence

To the literary critics who study the fairytale from

a diverse range of theoretical approaches, they have

found that Little Red Riding Hood was the first love of Charles

Dickens, who confessed, ‘‘I felt if I could have married

Little Red Riding Hood, I should have known perfect

bliss’’.(Beckett,2002) As Sandra Beckett (2002) has

claimed in her book Recycling Red Riding Hood, no folk or fairy

tale has been so persistently reinterpreted,

recontextualized, and retold over the centuries as the

story of Little Red Riding Hood. Some critics feel that, the

story of Little Red Riding Hood belongs to the ‘‘literature of

exhausted possibility’’ (Beckett, 2002). In addition to

the fairy tale being retold, it is undoubtfully the most

commented and criticised of all time.

In my research paper, I would like to focus on the

movie A Company of Wolves (1984), this media text is

illustrating and presenting puberty and adolescence,

through a twisted modernization of the classic story Little

Red Riding Hood. This movie explores the loss of childhood

5

innocence, purity and the corruption of the world of

adolescence, with the ingenious use of the dream

framework; and displays once a child ‘creeps out of the

children’s world into the world of adolescence’, there is

‘no way back` to the innocent children’s world. Thus this

is a depiction of the reflection of ideas of childhood in

the film, and not an artistic depiction of the actual

life. The film follows the dream framework from the very

beginning, portraying a young girl’s ‘fantasy world’

where ‘wolves run wild’. The rationale for choosing this

particular media text is because it mimics the

universally loved fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood, but it

explores the fairy tale in an intense symbolic and

metaphorical fashion. It is essential to state that the

fairy tale itself has been adapted in so many different

versions, this depicts how universally loved it is.

However, for these different adaptations to be;

‘‘Truly accepted as a classical fairy tale and

presumed ‘‘good’’ for the well being of children, a

narrative must be eminently rational..notions of the

acceptable treatment of children’’ (Zipes, 1993: 60).

In order to correctly ‘decode’ this movie, it is

essential not to see it in a ‘superficial flick’, but to

decode it as one would decode a literary piece, which

contains a lot of symbolic language. As Perrault

illustrates that all good fairy tales have ‘‘meaning on

many layers’’ (Cited in The Uses of Enchantment, 1991:169),

and that only the child can know which meanings are of

6

significance to him/her at the moment. As the child

matures, the child discovers, ‘‘new aspects of these

well-known fairy-tales, and this gives him the conviction

that he has indeed matured in understanding since the

same story now reveals, so much more to

him’’(Bettelheim,1991:169). This can only happen, when

the child is not told the real story behind the fairy

tale. Only the detection of the formerly hidden meanings

of a fairy tale, is the child’s spontaneous and imitative

achievement does it attain significance for him/her.

It is imperative to state that in the aforementioned

media text, exists four very essential ‘narrative

stories’ that occur; two of these stories are narrated by

the Grandmother, who has the role of Rosaleen’s (the

female protagonist) protector. As children were

traditionally presented as being in need of protection,

the other two of the stories that are narrated, are

narrated by Rosaleen herself. In these stories that are

being narrated, the viewers are being illustrated how an

innocent child loses her childhood innocence, and how she

becomes ‘corrupted’ as she enters the world of

adolescence. The ‘corruption’ of adolescence is further

demonstrated by the sexual, aggressive, bestiality in

men, and how this ‘evil’ in men also exist in women, thus

this demonstrates a construction of female and male

sexuality. These ideas in the film reflect on dominant

ideas of childhood, femininity and sexuality.

7

I would like to divide my research paper into three

different sub-sections to highlight three very essential

topics that contribute into my in depth- analysis. The

first sub-section is how fairy tales, have been used to

shape society and what the authors of Little Red Riding

Hood have to say. In addition the second sub-section is

about the film’s continuous motifs, metaphors & symbols.

While the third sub-section, is about the dominance of

story-telling in the Company of Wolves.

Sub-Section OneHow Fairy Tales Have Been Used to Shape Society, and

What The Authors Of Little Red Riding Hood Have To Say

In the first sub-section, I will illustrate and

depict how fairy tales have been used to shape society,

and what the authors of Little Red Riding Hood portray in their

different adaptations. Fairy tales have always played an

important role in shaping society, and their ‘deeper

messages’, have been used to teach ‘moral lessons’ to

children. It is essential to depict that fairy tales for

young people, predominantly children, cannot be detached

from the fairy tales for adults.

As Zipes states in his book Fairy Tales and the art of

subversion (2006), an individual can speak about the single

literacy fairy tale, or ‘wonder-tale’ for children as a

symbolic representation, permeated by the ideological

perspective of the individual author. Therefore it is

8

essential to incorporate the story of Little Red Riding Hood as

children’s cultures. It is also crucial to illustrate

that fairy tales for young people, predominantly

children, cannot be detached from the fairy tales for

adults as previously mentioned. Nearly all critics and

reviewers, who have mastered the emergence of the

literary tale in Europe agree, that; educated writers

deliberately appropriated the oral folktale and

transformed it into a type of literary discourse about

morals and values. So that children and adults would

become cultured according to the social order at that

time. Zipes states, ‘‘...Fairy tales operate

ideologically, to indoctrinate children so that they will

conform to dominant social standards, which are not

necessarily established on their behalf’’. (Zipes,

2006:34)

The fairy tales may be one of the most vital

artistic and social authorities in children’s lives,

especially the moral lesson that exists in the story of

Little Red Riding Hood. But it has been evident, until the

publication of the Art of Subversion; little attention had been

given to the traditions in which the authors and

collectors of tales used established forms and genres, in

order to form children’s actions, values and relationship

to society. As Zipes (2006) persuasively portrays,

‘wonder tales’ have always been a powerful discourse,

capable of being used to shape or subvert attitudes and

9

behaviours within culture. Zipes ask questions that link

the fairy tale to society and to our ‘‘political

unconscious’’.

I would also like to add that in Perrault’s stories,

especially his adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood; he didn’t

just want to entertain his audience, but to also teach a

specific moral lesson. His adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood

loses much of its appeal, because it is obvious that his

wolf is not a rapacious beast, but an actual metaphor,

which leaves little to the imagination of the hearer.

However there are elements presumably which evade the

intentions of the author. The same metaphor of the

‘wolves’ are used in the Company of Wolves, to mirror the

bestiality, the aggressive sexuality in men. Perrault

further illustrates as previously mentioned, that all

good fairy tales have ‘‘meaning on many layers’’, and

that only the child can know which meanings are of

significance to him/her at the moment. As Bettelheim

(1991:172) illustrates, The Brothers Grimm adaptation of

Little Red Cap also depicts the crucial problems the school-

age girl has to solve, if oedipal attachments linger on

in the unconscious, which may drive her to expose herself

to the prospect of seduction. This mirrors Rosaleen’s

character in the Company of Wolves, and how she is not just

‘seduced’, but she is also presented as a seductress. The

film is in parallel with the Little Red Cap, as the wolf does

10

not do anything ‘unnatural’ to the girl, and ‘‘nothing

that she did not want’’(The Company of Wolves,1984).

Thus this depicts Rosaleen’s seductive nature, and

corruptive nature, because of her loss of childhood

innocence. Rosaleen’s character subverts the traditional

image of the innocent, naïve child, she is provocative

and she is seen as a ‘seductress’. She portrays what

happens when a child loses his/her innocence and ‘creeps

into the adult world’. Thus this is a depiction of the

reflection of ideas of childhood in the film, and not an

artistic depiction of the actual life as previously

mentioned.

Sub-Section TwoThe Film’s Continuous Motifs, Metaphors & Symbols

In the second sub-section, I will illustrate and

emphasise the film’s continuous motifs, metaphors and

symbols which surround this media text. It is not

‘feasible’ not to ‘notice’ these continuous symbols; due

11

to the fact that they aid us to ‘decode’ this film

correctly, in addition, they help us to comprehend how

the ideas of childhood, femininity and sexuality are

‘represented’ and ‘constructed’ in the film.

The prevalence of essential moral struggle is very

much in existence in the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood. As

Patricia Cooper (2000:187) states, hyperdrama is served

in The Company of Wolves, for a dual purpose; firstly to mimic

the actual fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood, and secondly to

translate a fairy tale into a horror story. The above

film focuses on the female protagonist, Rosaleen, and the

stages she goes through to enter the adolescent world,

and how this reflects to the corruption of her childhood

innocence. As Bruno Bettelheim (1991:172) demonstrates,

the film’s underlying goal is to educate moral

instructions to the leading heroine about the

relationship of the world’s they find themselves in. Little

Red Riding Hood is universally loved because, although she

is moral, she is tempted; and because her fate tells us

that trusting everybody’s good intentions, which seems so

nice, is really leaving oneself to fall in the ‘trap’.

Thus reminding the audience that the ‘‘Sweetest tongue

has the sharpest tooth’’ (The Company of Wolves, 1984).Thus

reflecting on the traditional ideas of femininity,

sexuality and childhood innocence.

According to an online analysis (2007), the film

necessitates its viewers to enthusiastically engage the

key themes from each scene, and is not appropriate for

12

those only prepared to observe a ‘superficial horror

flick’. This film can be seen to be in parallel with

horror films, with werewolf narratives, however the

werewolf narrative is used to depict female sexuality and

the sexual aggressive nature which exists in men. This

media text draws the viewers into a mental landscape; it

captures them and draws them into the distressing world

of a little girl’s wild fantasy world, situated in a

fairy tale-like setting. The movie is produced and

directed in such a way, to capture the audience, making

them feel as if they are ‘trapped in a fairy tale`

themselves. The ghostly and unearthly scenery builds up

into a Freudian nightmare, illustrating puberty through a

twisted modernization of the classic story “Little Red Riding

Hood’’ as aforementioned. For Freud there is no tabula rasa,

therefore, there is no innocent child, this is developed

in the film’s ‘dream framework’, where we are depicted

dominant ideas of sexuality which exist within children,

and how this sexuality causes the loss of childhood

innocence.

One of Angela Carter's themes and concepts that are

essential in this movie, is that the corruption of

adulthood is unconditional, thus reflecting on the ideas

of sexuality. When one enters the world of adulthood,

there is no preservation of innocence and purity of

youth; this is when there is no way back. Thus this is a

depiction of the reflection of ideas of childhood in the

13

film, and not an artistic depiction of the actual life,

as previously mentioned. In addition the ideas of

childhood in the film are presented as a temporary

identity. The viewers are presented and illustrated a

juxtaposition of the protagonist’s innocence, displayed

by her childhood toys and dolls in her room at the very

start of the film. Juxtaposed with the toys, the sleeping

Rosaleen is seen to be wearing smudged red lipstick, with

a magazine lying next to her that has a symbolic title,

‘‘The Shattered Dream". The title is not only hidden with

symbolic meanings but it is also ominous, as Rosaleen’s

‘dream of her childhood innocence is soon to be taken

away’. This is a Freudian outlook of children’s dreams

about sexuality.

On her door hangs a white chiffon dress, symbolizing the

path of her entering into womanhood and adolescence. This is

illustrated at the finale of the movie, where the viewers try to

‘catch their breath’, as they view ‘the wolf’ invading her room,

symbolising the destruction of Rosaleen’s innocence. The viewers

are presented with strong visual imagery, as they see Rosaleen’s

childhood toys being ‘destroyed’ by the wild wolves invading her

room, the same way she is being destroyed and corrupted

metaphysically. The vividness of this scene is out of the world,

the aim for the destruction of her childhood is indisputable.

Her cry can be interpreted to symbolise her comprehension and

acknowledgment of what she must lose to enter into the adult

world. This scene differs from the literary text, where the loss

14

of childhood innocence is seen as a more positive act. However in

contrast with the film, which follows the Freudian dream

framework, they have represented this scene, in an intense

‘horror narrative’. Thus this is portraying sexuality in a

‘horrific fashion’.

Thus illustrating, what happens when people grow up,

they put their toys away in the attic as if they were ‘gone

forever’, symbolising the ‘death of innocence’. Thus this

reproduces dominant ideas of childhood, and how a child’s

innocence becomes corrupted as they enter adulthood, because of

a child experiencing sexuality. The background music in the

beginning of the film is ominous, it adds up the tension

throughout the film, until it reaches its final climax.

As soon as the first scene is about to enter the dream framework,

poignant music is played, reflecting on the atmosphere, the mood of

the scene. Alice, Rosaleen’s sister is presented in the

protagonist’s dream, and how she is being attacked by a sailor toy

and a human sized teddy bear. This act is symbolic. The childhood

toys that are attacking the protagonist’s sister, Alice, are being

rebellious. Due to the fact that Alice, has entered the adult world

and she is now too old to be playing with her toys. In addition the

large ticking clock also stands as a symbol and a metaphor in this

scene, as it is reinforcing that time passes too quickly, and Alice

does not belong in the children’s world anymore. Thus this scene

illustrates ideas of childhood and sexuality.

Alice’s final ‘death’ to her childhood innocence is when she

is attacked by a pack of wild wolves in this scene, where they

15

‘kill’ her savagely. This scene can be interpreted in so many

different ways. My belief is that her ‘death’ was metaphysical as

she was possibly ‘raped’ by men or sexually abused. These sexually

aggressive men in this scene are presented as wild beasts, - in the

form of ‘wolves’ to emphasise the aggressive sexual nature of men.

This scene can be interpreted as the arrival of sexuality, which is

represented in a conservative construction of childhood. In

addition this scene refers to Freud, and how he claimed that all

children were sexual. The two worlds of the dream and the reality

world of the girl exist in this film, to portray that a young girl

is free to dream about sexuality and the passage of womanhood.

However in reality sexuality sometimes has to be repressed, whereas

young girls are liberated to dream sexually. Alice’s cry depicts

her helpless nature, and how women were traditionally represented

as the ‘weaker sex’. At Alice’s funeral her mother tells Rosaleen,

‘‘Kiss your sister goodbye for the last time’’. This quote should

not be taken literary; she is actually depicting ideas of loss of

childhood innocence, representing the ‘death of childhood’. Thus

the funeral stands as a symbol to the ‘burial of childhood purity’.

As Diane Herman(1998) has pointed out in her important essay, ‘The

Rape Culture’, ‘‘the imagery of sexual implications between males and

females in books, songs, advertising and films is frequently that of

sadomasochist relationship thinly veiled by a romantic façade. Thus

it is extremely difficult in our society to differentiate rape, from

‘normal’ heterosexual intercourse; relations undeniably our culture

conduct, as a result that she faces the possibility of rape’’.

16

Figure 1

According to an online analysis (2007) of the film,

Rosaleen’s red cape is symbolic to her childhood

innocence, the cape was originally made to keep her safe

as well as hide her feminine body from the male world.

While Rosaleen states that the cape is comforting,

"...soft as a kitten," it becomes apparent, that the cape

must be ‘destroyed’ symbolically losing her innocence, in

order for her to enter into the adult world. The Hunter

later on in the movie tells her "...into the fire with

it, you won't need it again," this portrays the hunter’s

lust and his strong passion to burn the child’s innocence

to try to wake up the dormant woman in her. A further

interpretation I would like to demonstrate is, the colour

of the red shall, can also stand as a symbol of the

provocative nature of Rosaleen, and how she will follow

the path towards adulthood, this portrays the loss of

childhood innocence and purity, the colour red reinforces

female sexuality, and femininity.

This media text has a problematic status, because of

the fact that the viewers are presented with a young girl

17

that subverts the traditional image of the sweet innocent

little girl. This is ironic, as her grandmother’s

function in the story is to guide her precious

granddaughter to ‘‘not stray from the path’’, but the

colour of the shawl reinforces sexuality, feminine desire

and womanhood. Thus this depicts the adult-child power

relations in this media text.

The symbolic death of her grandmother’s head being

shattered like glass, and the red shawl liberates

Rosaleen free to mature, to enter the world of the

‘wolves’, as it is illustrated in the film to portray the

corrupted state of adolescence. As in Freud's analysis of

dreams, Rosaleen's dream deals with her ‘inner demons’-

her repressed sexuality, thus portraying elements of her

psyche as characters in her dream. In Rosaleen's dream,

her Grandmother ‘‘symbolizes the path of rules, care, and

fright’’. In her dream Rosaleen is warned by her

Grandmother to never "stray from the path… Once you stray

from the path you're lost entirely! The wild beasts know

no mercy’’. What the Grandmother is really saying is ‘‘to

stay on the path of celibate adolescence leading to

marriage and to beware of the bestial, aggressive

sexuality of men’’ (Hyldreth, 2008).

"Oh, they're nice as pie until they've had their way with

you. But once the bloom is gone, oh, the beast comes

out." What her grandmother is actually trying to warn her

is, how men ‘transform’ when they have their ‘evil way’

18

with a woman, displaying their true colours, this scene

depicts dominant ideologies of male sexuality.

A further interpretation of her Grandmother’s

constant warning of ‘‘don’t stray from the path’’, can be

interpreted in a radical feminist way- in their view of

the aggressive sexuality of men and their dominance over

women. A child has been traditionally portrayed in the

need of protection, thus this highlights the function of

the grandmother in the film. This can be associated with

the Brothers Grimm adaptation of Little Red Cap, ‘‘as her

mother is aware of Little Red Cap’s proclivity for straying

off the beaten path, and for spying into corners to

discover the secrets of adults’’. (Cited In The Uses Of

Enchatment, 1991). Thus this reinforces the dominant ideas

of childhood and sexuality.

Figure 2

The film deal with the theme, of the protagonist’s

developing sexuality in a magical series, as if it is

mimicking a fairy tale setting. In which she suddenly

breaks out of the scenery of the dream world and climbs a

19

tree. At the top of a tree she finds an abandoned bird’s

nest containing eggs and a hand mirror. As Damon Hyldreth

(2008) illustrates, she magically finds a red lipstick

and wears it and admires herself in the mirror, at the

same time the audience is taken back to Rosaleen’s room

where she is sleeping restlessly- there are a lot of

references to the sleeping Rosaleen in the movie. The

mirror in her bedroom and the lips smudged with lipstick

is being displayed. The eggs, the visual demonstration of

the ‘unbroken egg’, (Cartmell, et al 1998:52) of the

short story, crack open to reveal figurines of babies,

representing Rosaleen’s passage into adulthood, her

sexual latent The protagonist’s personal traits

challenges prevailing attitudes, towards the institution

of childhood, due to the fact that this particular scene

reflects on the ideas, of female sexuality, and the loss

of childhood innocence.

As the authors of Sisterhoods (1998:52) state that,

the juxtaposition of the hand mirror, red lipstick and

eggs, symbolise the socially and biologically determined

aspects of femaleness. This particular scene serves as a

form of ambiguity, not only depicting the protagonist’s

adolescent state, through an economic use of symbolic

taken directly from the literary book, but also

reinforcing female subjectivity via visual references to

the dream structure. (Cartmell, et al 1998:52)

20

As Damon Hyldreth (2008) portrays, the viewers are

presented with our protagonist moving her young delicate

figure forward as she takes one of the gleaming tiny

figures, placing it in her pocket. As Rosaleen returns

home through the woods to her horror, she comes across to

a large ‘wolf’ sitting above her on hill. As she walks

approving the tiny little statuette in her hand she seems

impervious to the wolf. When she returns home, she shows

the figurine to her mother and we see a close up of the

figurine. Rosaleen's seeing herself in the mirror as a

woman and retrieving the tiny figurine of a man

symbolizes, that she has the awareness of herself as a

woman with power to give birth, birth not only to a baby,

but to her own adult self; this symbolises the corruption

of adolescence, and the loss of her childhood innocence.

This scene also makes references to the beginning of the

movie. When it is stated in the movie that she has a

‘‘tummy ache’’.-reflecting on her menstrual cycle, also

the red lipstick is ominous to her destiny, this reflects

in her development as a woman. Thus this reflects the

traditional ideas of female sexuality, and the loss of

childhood innocence.

In the aforementioned story the grandmother which

symbolises wisdom and knowledge is also an adult wolf. It

is essential to critically analyse the term ‘wolf’ in

this text, the motif, the ‘icon’ of the ‘wolf’, should

not be taken literally but metaphorically. The ‘wolf’

represents, experience and acknowledgment of the real

21

world. It is essential to display that the grandmother

narrates two very significant stories to Rosaleen,

because according to her a ‘‘child is never young enough

to know’’. (The Company of Wolves, 1984) Thus this is once

again reinforcing and highlighting dominant ideas of

childhood and sexuality, represented in this film.

22

Sub-Section ThreeThe Dominance Of Story-Telling in the Company of Wolves

In the third sub-section, I will illustrate and

present the dominance of ‘story-telling’ that exists in

this film. ‘Story-telling’ reflects upon issues of

childhood and socialisation. Traditionally children were

told stories by their parents, as a way of indoctrinating

them into dominant values including their own situation

as children. Two of the ‘narrative stories’ are told by

the Grandmother and the other two ‘narrative stories’,

are narrated by the Protagonist herself.

In one of her narratives, the Grandmother tells a

story to our protagonist about a newly wed in the

village, and how her husband disappeared on their wedding

night because of ‘‘call of nature’’. I would like to

critically analyse and examine this quote, the groom’s

disappearance contains ambiguity, and his actions can be

interpreted as the ‘unfaithful’ husband, who abandoned

his wife on their wedding night. This possible analysis

can be coo-related with the reappearance of the husband

after a long period of time to find his wife in her

23

second marriage making supper for her children. His

aggressive gesture towards his wife is highlighted when

he violently slaps her on the face calling her a

‘‘whore’’ and ‘‘if I was a wolf once, I’ll be a wolf

again’’. All this, add up to his aggressive, uncouth

nature, his bestiality, and his unfaithful nature. He

violently removes his skin and metamorphosis’s into a

wolf to attack his wife, but when the wife’s second

husband marches in the room, he chops his head off and he

immediately transforms back into a man. Carter could

possibly have created this, in order to mirror the fact

that even if there is ‘bestiality’ and ‘abusive nature’

in men, this does not change the fact that he is still

human. The scene portrays the grandmother’s collusion in

patriarchal accounts of gender relationships.

For Anwell (1988), these violent transformation

scenes are inherently connected, to aggressive, masculine

sexuality. Anwell also argues that the film, ‘‘surrenders

to the commercial pressures of mainstream cinema in the

use of expensive, state-of-the-art animatronics to effect

the werewolf metamorphoses’’. Avis Leewallen (1988)

quotes at length from this passage in Duncker’s essay,

but departs from Duncker’s analysis in the recognition of

the use of ‘‘an inner confessional narrative’’, which

both acknowledges patriarchal structure, and provides a

form of critique against it.

Her grandmother’s second narrative story is about a

boy who meets the ‘Devil’ in the woods. It is essential

24

to decode and interpret this scene in a symbolic fashion.

A car appears out of nowhere in the forest, a car driven

by Rosaleen who is presented in an altered way, wearing a

blonde wig. The viewers are presented with Rosaleen’s

provocative greeting smile, when she opens the door to

introduce the boy to the ‘Devil’; this scene reminds the

viewers when Rosaleen’s mother states, ‘‘if there is evil

in men. There is evil in women too’’. The ‘Devil’ hands

the boy a potion while he is holding a skull in his hand,

when the car vanishes from the woods, the boy opens the

magical potion and puts some drops on his body. We are

then illustrated with a magical transformation of the boy

into a ‘wolf’, where the body hair grows on the boy,

making him scream in pain, as he ‘transforms’.

Thus the scene portrays how a boy violently

transforms into an adolescent and how this ‘wolf

transformation’ is a natural act this is further evident,

when the viewers are presented with the tree’s roots

aggressively capturing the boy. This symbolises that the

‘werewolf transformation’ is a natural act as

aforementioned. In Jordan's film the ‘werewolf’

transformation is linked directly to male sexuality; here

we see the devil encourage a young man into the sexual

sphere. The scene endorses parts of an old legend. One

of the ways to turn into a werewolf is to drink such a

potion, this scene can also be interpreted in another

way; the car itself represents the ‘wolf’-adolescence.

The idea relates to the male lust, and this lust is

25

produced and created by women, and the source of this

lust is the ’Devil’-the evil in men. This is symbolically

a rich moment indoctrinating and constructing gender and

sexuality in the film. ‘‘That’s a horrid story’’, is the

response of the heroine, thus reflecting Rosaleen’s

denial of male sexual aggression, and a woman’s power to

provoke and to seduce men. This scene depicts gender

representation, the construction of male and female

sexuality as previously mentioned, and the loss of

childhood innocence, because of the existence of

‘sexuality’ in this film.

This scene, can contradict Maggie Anwell’s (1988)

reading of powers relations in the movie, because this

scene mirrors the subversion of gender power-relations

which are represented throughout the movie.

As Henry Jenkins (1998:261) would suggest, the

film’s theme of these ‘‘children’s cultures contains

these adult fantasies. It contains the transformation of

this into a projection on to children of the adult

language of lust and craving. In this view the little

seductress is a multifaceted phenomenon, which contains

adult sexual lust, but which captures into the equally

complex fantasies carried by the little girl herself’’.

The child is theologically constructed as, ‘‘One view

stressed the angelic natural goodness of children the

other stressed their devilish, potentially evil, self-

willed nature’’.(1972:8) As a sample of the first view,

Shipman quotes from the essayist, John Earle,

26

subsequently Bishop of Salisbury, who in 1628, at the age

of eighteen wrote in Microcosmographic.‘’The child is the

best copy of Adam before he tasted of Eve, or the apple,

and he is happy whose small practice in the world can

only write his character..’’(Shipman, 1972:9). Thus this

latter quote displays the corruption of childhood

innocence, due to the existence of ‘sexuality’.

Figure 3

The third story that is being narrated in the film

is narrated by the female heroine of the media text

Rosaleen, and the story is being addressed towards her

own mother. Thus this scene demonstrates a dramatic

reverse between adult-child power relations. The viewers

are portrayed with a subversion of power relations, where

the adult- the mother is presented to be the listener,

and the child is depicted as the story teller. Story-

telling reflects upon issues of childhood and

socialisation, as aforementioned. Traditionally children

were told stories by their parents, as a way of

27

indoctrinating them into dominant values including their

own situation as children. Carter’s story is being

critical of this, as we are presented subversion between

the adult/child power relations.

In Rosaleen’s story the viewers are taken to a

wedding scene, where the aristocratic bride and groom

have just exchanged their vows, and they are seated at a

dinner party along with their guests. Out of nowhere a

pregnant Irish woman enters the dinner party, disturbing

the guests with her presence. With her presence, she

makes it quite obvious that the groom had committed

something so terrible, leaving the girl pregnant. Her

statement that the ‘‘wolves in the forest are more

decent’’, can be interpreted how the wealthy and the

aristocratic families can be described as everything,

besides ‘decent’. She compares the wealthy with the

actual ‘wolves’ in the forest, to depict that they are

worst then the actual wild creatures living in the

forest. Thus this quote reinforces the aggressive nature

of men’s sexuality.

As soon as she turns around to look at the mirror,

the mirror cracks, transforming all the guests into

‘wolves’, this symbolic and metaphysical transformation

has a very essential meaning in this scene. The ‘witch’

portrays the ‘power’ to unmask the Aristocratic guests

and to reveal their ‘true colours’. The story narrated by

Rosaleen, is not about ‘werewolf transformations’, but

the ‘wolf’ image has been used to present the

28

animalistic, deceitful behaviour of the aristocracy. This

scene depicts gender representation and the construction

of male and female sexuality. ‘‘The use of circus music

and extensive camera movement produce a carnivalesque

atmosphere, reinforcing the facade of kitsch

intertextuality’’. (Cartmell, et al 1998:52) Catherine

Neale (1996) suggests that ‘‘this is an intentional

alienation technique which ultimately fails’’, arguing

that ‘‘in the decision to sacrifice the illusion of

transformation at this point in the film, presumably in

order to force the viewer to appraise what they are

seeing, elements of bathos and banality cannot be

controlled’’.

It is hard not to notice the parallel between the

texts of A Company of Wolves, and Disney’s Beauty & The Beast, when

one analyses the ‘aggressive, sexuality in men’, which is

represented by the Beast, in the Beauty & The Beast. An

essential paradigm can be illustrated when the Beast

screams at Belle, when she refuses to dine with him he

screams, ‘‘Then you can starve!’’. The Beast represents

and stands as a symbol of the uncouth Aristocrat, who is

aggressive and brutal, similarly the ‘Aristocrats’ in

Company of Wolves are portrayed as ‘less decent then the

wolves living in the forest’. Henry Giroux (2001) states

that, ‘‘enchantment comes at a high price, however if the

audience is meant to suspend judgment of the film’s

ideological messages’’ (2001:96). This statement

highlights in order to comprehend the representation of

29

aggressive, heterosexual nature of men, it is essential

to decode the ‘ideological messages’, as previously

stated.

A very significant point to illustrate is that the

story is narrated by the female protagonist of this media

text, thus subverting the traditional image of children

being naïve and innocent. Firstly, for Rosaleen to

narrate such a story to her mother does not only reverse

power relations between adults and children as

aforementioned; but it also demonstrates Rosaleen’s

acknowledgment and comprehension of the path towards

adolescence and the corruption of her own childhood. The

fact that Rosaleen is narrating the story, illustrates

she has the power to be in control and through her story,

it is evident that she is aware that ‘‘wolves may lurk in

every guise’’. (A Company of Wolves, 1984)

As Damon Hyldreth (2008) depicts, as Rosaleen

narrates her second story, which is addressed to the

wolf, we see a white rose in full bloom opening in slow

motion. As it opens it begins to turn deep blood-red

turning completely red when fully open. The rose

symbolises Rosaleen, depicting that her development as an

‘adult wolf’ is complete; she has found her male partner

and domesticated the ‘beast ’within him. The

‘transformation’ of the white rose turning into a red

rose, portrays Rosaleen’s innocence being destroyed, the

colour of the rose reinforces her menstrual cycle-her

30

metamorphosis into an adult wolf has been completed. It

is vital to display that, the ‘wolf’ is not just the male

seducer, but he also represents all the asocial,

animalistic tendencies within us. Traditionally roses

were symbolically used to depict sexuality, femininity

and passion.

Anwell (1988) offers a sensitive reading of Carter’s

sexual politics in the story; by declining to abandon the

logic of the gaze, Anwell misguidedly interprets the film

as reinforcing the patriarchal victim/aggressor approach

of the original fairy tale. By emphasizing ‘the struggle

to speak female desire’, she disregards the essential

role of the female voice and story-telling in her

enthusiasm to censure the film for a voyeuristic

portrayal of the female protagonist.

There are a number of significant and vital themes

that surround this film. An imperative paradigm is, at the

very end of the movie, the viewers see the protagonist’s

dream world collide with ‘the real world’. The last

series of events build up with tension as the viewers are

close to the final climax, keeping the audience in

constant suspense. We the viewers see Rosaleen reaching

her destiny- losing her childhood innocence and her final

‘metamorphosis’ and final ‘transformation’ from an

innocent child into an ‘adult wolf’. Thus this media

text, constructs not only children’s audience but also

adult’s audiences. This scene is vital as the audience

31

‘sees’ the Freudian dream framework being collided with

the world of reality. Rosaleen’s sexuality and her

passage into womanhood from her dreams have now been

collided with her world of ‘reality’.

32

Conclusion

To conclude this research paper, I have focused

on the movie A Company of Wolves and have depicted how this

media text, represents puberty and adolescence through a

twisted modernization of the classic story Little Red Riding

Hood, as aforementioned. This media text as previously

mentioned, explores the loss of childhood innocence,

purity and the corruption of the world of the

adolescence, with the ingenious use of the dream

framework. This film portrays once a child ‘creeps out of

the children’s world into the adult world’, there is no

‘way back’. However this is a depiction of the reflection

of ideas of childhood in the film, and not an artistic

depiction of the actual life. It has been evident that in

order to correctly ‘decode’ this film, it is essential

and vital not to ‘see’ it in a ‘superficial flick’, but

to decode it as one would decode a literary piece, which

contains a lot of symbolic language. It is crucial to

depict that in the aforementioned media text, exists four

very essential ‘narrative stories’ that occur as

33

previously mentioned; two of these stories are narrated

by the Grandmother, who has the role of Rosaleen’s (the

female protagonist) protector. As children were

traditionally presented as being in need of protection,

the other two of the stories that are narrated, are

narrated by Rosaleen herself. In these stories that are

being narrated, the viewers are being illustrated how an

innocent child loses her childhood innocence, and how she

becomes ‘corrupted’ as she enters the world of

adolescence. The ‘corruption’ of adolescence is further

demonstrated by the sexual, aggressive, bestiality in

men, and how this ‘evil’ in men also exist in women, thus

this demonstrates a construction of female and male

sexuality. These ideas in the film reflect on dominant

ideas of childhood, femininity and sexuality.

Bibliography Badley, Linda (1995) Film, Horror, and the Body Fantastic

[Online].Available from URL:http://books.google.com/books?id=PD1CZfa5wicC&pg=PA104&dq=anti+feminism+in+company+of+wolves#PP P11,M1

34

[Accessed November 2008]

Beckett, Sandra (2002) Recycling Red Riding Hood [Online].Available from URL:http://books.google.com/books?

id=LapMimSid7kC&pg=PA147&dq=decoding+little+red+riding+hood#PPR17,M1

[Accessed November 2008]

Bettelheim, Bruno (1991) The uses of enchantment: the meaning and importance of fairy tales. London: Penguin.

Cartmell, Deborah et al. (1998) Sisterhoods:[Online].Available fromURL:http://books.google.com/books?id=MM7lkyefGisC&pg=PA48&dq=analysis+of+company+of+wolves#PPA1,M1

[Accessed November 2008]

Carter, Angela (1940-1992) Come unto these yellow sands. -Newcastle upon Tyne : Bloodaxe

Carter, Angela(1984) The Company of Wolves [OnlineImage].Available from: URLhttp://images.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://thisdistractedglobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/06/Wolves4.jpg&imgrefurl=http://thisdistractedglobe.com/2006/03/09/the-company-of-wolves-1984/&usg=__eRuvH9x8t5d4UnT20GUkeuXWQx0=&h=208&w=160&sz=9&hl=en&start=61&tbnid=ZqsfBG6QRXpTRM:&tbnh=105&tbnw=81&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dthe%2Bcompany%2Bof%2Bwolves%26start%3D60%26gbv%3D2%26ndsp%3D20%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DN

[Accessed December 2008]Carter, Angela (1984) The Company of Wolves [Online

Image].Available from: URLhttp://images.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://www.bombsite.com/images/attachments/0001/5525/

Carter_01_body.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.bombsite.com/issues/17/articles/

821&usg=__diToOuqmIanw_NqGmFgKrpDbyR4=&h=557&w=548&sz=166&hl=en&start=96&tbnid=6CP4sSNS7EreiM:&tbnh=133&tbnw

35

=131&prev=/images%3Fq%3D%2527a%2Bcompany%2Bof%2Bwolves%2527%26start%3D80%26gbv%3D2%26ndsp%3D20%26hl%3Den

%26sa%3DN[Accessed December 2008]

Cooper, Patricia& Dancyger, Ken (2000) Writing The Short Film, [Online]. Available from: URL

http://books.google.com/books?id=rRmcrT5JL-4C&pg=PA187&dq=Writing+the+Short+Film+By+Patricia+Cooper,+Ken+Dancyger+company+of+wolves

[Accessed December 2008]

Giroux, Henry (2001) The Mouse That Roared [Online]. Available from: URLhttp://books.google.com/books?id=y4JIvzl547UC&pg=PA92&dq=analyzing+disney%27s+beauty%26the+beast#PPA96,M1

[Accessed December 2008] Hyldreth, Damon (2008) The Company of Wolves [Online].

Available from URL:http://www.damonart.com/myth_wolves.html

[Accessed November 2008] Hyldreth, Damon (2008) The Company of Wolves [Online

Image]. Available from URL:http://www.damonart.com/myth_wolves.html

[Accessed November 2008]

Jackson, S. (1984) ‘ Chapter 3: ‘The Nature of Childhood’ in Childhood and sexuality Oxford & New York: Blackwell pp.22-46

Jenkins, Henry (1998) The Children’s Culture Reader. New York University Press, New York and London

Kirkland, Ewan (2008) ‘Overview` [Online]. Available from: URL

http://lms.king.ac.uk/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_id=_2_1&url=%2fwebapps%2fblackboard%2fexecute%2flauncher%3ftype%3dCourse%26id%3d_5795447_1%26url%3d

[Accessed December 2008]

36

Mills, J and Mills, R (2000) Childhood Studies: a Reader in Perspectives of Childhood. London: Routledge

The Company of Wolves (2007) [Online]. Available from URL:

http://www.geocities.com/za5tar/thecompanyofwolves.html

[Accessed November 2008]

The Company of Wolves (1984) Directed by, Neil Jordan[DVD], Shepperton Studios, Shepperton, Surrey,England, UK

Zipes, Jack (2006) Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion,[Online]. Available fromURL:http://books.google.com/books?id=Z89TEYxprOoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Fairy+tales+and+the+art+of+subversion+:+the+classical+genre+for+children+and#PPP1,M1

[Accessed November 2008]

37