An Investigation into High Quality Leader Member Exchange Relatio

Transcript of An Investigation into High Quality Leader Member Exchange Relatio

University of South FloridaScholar Commons

Graduate School Theses and Dissertations Graduate School

1-1-2011

An Investigation into High Quality Leader MemberExchange Relationships and their Relation toFollowers' Motivation to LeadMichael RossiUniversity of South Florida, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etdPart of the American Studies Commons, and the Psychology Commons

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion inGraduate School Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please [email protected].

Scholar Commons CitationRossi, Michael, "An Investigation into High Quality Leader Member Exchange Relationships and their Relation to Followers'Motivation to Lead" (2011). Graduate School Theses and Dissertations.http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3300

An Investigation into High Quality Leader Member Exchange Relationships and

Their Relation to Followers’ Motivation to Lead

by

Michael Rossi

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree

Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida

Co-Major Professor: Russell E. Johnson, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Michael Coovert, Ph.D.

Jennifer K. Bosson, Ph.D. Tiina Ojanen, Ph.D. Paul Spector, Ph.D.

Date of Approval March 25, 2011

Keywords: 360 assessment, leadership competencies, federal leaders, role models, leader performance

Copyright © 2011, Michael Rossi

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables iii

List of Figures iv

Abstract v

Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Motivation to Lead (MTL) 3

Affective-Identity MTL 5 Social-Normative MTL 5 Noncalculative MTL 6

Antecedents of MTL 7 Personality Traits 7 Cultural Values 8 LSE 9 Past Leadership Experience 9 LSE as a mediator between distal antecedents and MTL 10 Observed leadership as a proposed new antecedent to MTL 10

The Cascading Effect of Leadership 11 Relationship of Observed Leadership with MTL 14 Leader Member Exchange (LMX) 16 A Competency Based View of Leadership Effectiveness 20 Relationship of MTL to Leadership Criteria 22 Summary of Proposed Study 27

Chapter 2: Method 28 Participants 28

360 Participants 28 360 Raters 28

Measures 28 MTL 28 LSE 29 LMX 29 Leadership Competencies 29 Perceived Supervisor Leader Effectiveness 30 Control Variables 31

Procedure 31

ii

Data Cleaning 33 Scoring 33

Chapter 3: Results 36

Chapter 4: Discussion 49 Role-Modeling and MTL 49 MTL and Leadership Performance 51 Academic Implications 52 Applied Implications 53 Limitations 54 Future Research 58 Summary 59

References 61

Appendices 68 Appendix A: OPM Leadership 360 Competency Definitions 69 Appendix B: OPM Leadership 360 Items 72 Appendix C: Supplemental Survey 78

iii

List of Tables

Table 1: Study Variables, Descriptive Statistics and Correlations 37

Table 2: OPM Leadership 360 Assessment Descriptive Statistics 38

Table 3: Correlations between 360 Rating Groups on Overall Performance 39

Table 4: Intraclass Correlation Coefficients 39

Table 5: Regression Results for Perceived Supervisor Leader Effectiveness Predicting LSE and MTL 40

Table 6: Regression Results for Moderation Analysis 42

Table 7: Regression Results Predicting Leader Performance 45

Table 8: Regression Results Supervisor Rating Predicting Leader Performance 45

Table 9: Regression Results Peer Rating Predicting Leader Performance 46

Table 10: Regression Results Subordinate Rating Predicting Leader Performance 46

Table 11: Test of Group Differences 47

iv

List of Figures

Figure 1: Portion of Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) MTL Model 13

Figure 2: Slope Illustration for Moderation of LMX on the Relationship between Perceived Supervisor Leadership Experience and LSE 42

Figure 3: Slope Illustration for Moderation of LMX on the Relationship between Perceived Supervisor Leadership Experience and Noncalculative MTL 43

v

Abstract

This research further investigates the motivation to lead (MTL) construct and its

antecedents. While existing research has investigated culture, personality, and direct

experience as an antecedent to MTL, the indirect experience of observing an effective

leader has not been studied. It was hypothesized that having an effective supervisor

would be related to followers’ leadership self efficacy and MTL. It was also hypothesized

that this relationship would be moderated by the quality of the relationship between

leader and follower. Little evidence was found supporting these hypotheses. In addition,

the existing research into MTL has failed to establish the link between MTL and leader

performance. Using leadership 360 ratings as a proxy for leader performance, no support

was found linking MTL with leader performance. Academic and applied implications are

discussed.

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

The academic study of leadership is nearly 80 years old (House & Aditya, 1997),

and has experienced the cyclical trends that would be expected within any area of

research with such an extended history. Early leadership research focused on the

characteristics of the leader and was rooted in the great man theory. This theory posited

that leaders possessed character and personality traits that distinguished them from

followers (Carlyle, 1841/1907). Trait research dominated this initial leadership paradigm.

Traits such as dominance, assertiveness, physical stature, social sensitivity, and perhaps,

most importantly, intelligence, were extensively studied in early leadership research

(Chemers, 2000). Stogdill’s (1948) influential critique of trait research initiated a trend

away from such a focus, finding that while a few traits were often associated with

leadership, there was no single trait profile which could predict leadership across varied

situations. While the trait approach to leadership fell from favor in the late twentieth

century, more recent research has begun to again consider the explanatory power of

individual differences for predicting leadership effectiveness. One individual difference

variable that has emerged in recent years is the concept of motivation to lead (MTL)

(Chan & Drasgow, 2001). MTL is a malleable individual difference variable that affects a

person’s desire to assume leadership roles and partake in leadership development

opportunities, which in turn affect such person’s effort and persistence at taking on and

excelling in future leadership roles.

2

Chan and Drasgow’s work (Chan, 1999; Chan & Drasgow, 2001) proposes that

people possess a motivation to lead that is distally influenced by personality and cultural

factors, and more proximally influenced by leadership self-efficacy (LSE). This

individual characteristic of MTL affects people’s willingness to take on leadership roles

and training, which is then related to their overall leadership effectiveness. The quantity

and quality of these leadership experiences feed back into people’s LSE and future MTL.

While it is clear that MTL derives in part from personality and culture influences, this

motivation has a malleable component such that leadership-related training and

experiences may also impact LSE and MTL.

The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate further the experiential basis of

MTL, focusing on additional mechanisms of MTL formation. While direct leadership

experience and formal leadership training are certainly important for building LSE and

MTL, people’s observation of, and experiences with, their leaders may have an influence

on their individual LSE and MTL. Having a quality leadership role-model serves as a

learning opportunity similar to formal leadership training which may impact people’s

LSE and MTL. In addition, the benefits of this leadership role-model can be enhanced by

having a high quality leader member exchange (LMX) relationship with the leader. This

dissertation will investigate the relationship between LMX, leader behaviors, and

follower MTL; explore the outcomes related to MTL; and shed light on the relation of

MTL with leader performance.

Developing a more comprehensive view of leadership, with a focus on what

motivates an individual to want to take on leadership roles, is important from both

theoretical and practical perspectives. Leadership research and theory have often ignored

3

the motivational component of leadership, and have focused more on assessing the

qualities of good leaders. While developing an understanding of the knowledge, skills,

and abilities associated with successful leadership is certainly a worthwhile academic

endeavor, equally important is developing an understanding of why some unqualified

individuals pursue leadership roles, and why some exceptionally qualified individuals do

not. From an applied perspective, many organizations are placing an increased emphasis

on leader development, and on identifying the next cadre of high potential individuals

early on in their careers. Identifying high potential individuals is an exercise not only in

assessing qualifications, but also in determining desire. Chan and Drasgow’s (2001)

research on MTL is a first step at improving our understanding of the ‘why’ of

leadership, but it ignores the experiential mechanism of interacting with leader role

models. Developing a more comprehensive understanding of MTL by including a focus

on the impact of leaders on followers’ MTL will continue to provide answers to the

‘why’ question of leadership while also shedding light on the importance of leader-

follower relationships in the workplace. Below I present brief reviews of pertinent

leadership research along with hypothesized relationships.

Motivation to Lead (MTL)

Chan and Drasgow (2001) posit that there are non-cognitive ability constructs

such as personality traits and values that make people more or less likely to engage in

leadership related behaviors, which in turn impact their participation in more formal

leadership roles. Chan and Drasgow refer to this desire to engage in leadership roles as

the motivation to lead. People’s MTL, in combination with their ability, are the two

crucial person-based factors that influence leadership behavior. People who are motivated

4

to lead, possess the cognitive ability to do so, and find themselves in situations with

opportunities for leader emergence, will partake in leadership behaviors that will lead to

positive leader outcomes. These positive outcomes in turn will reinforce their MTL,

resulting in further leadership behavior. Conversely, those with low MTL will shy away

from opportunities to lead which in turn will result in less leadership experience that will

perpetuate the low MTL in the future.

MTL is not proposed to be an innate trait fitting into the great man theories of the

early leadership research, rather it is proposed to be a malleable individual difference

variable. Chan and Drasgow (2001), in their validation of the MTL scale, investigated the

non-cognitive antecedents of MTL. They showed that the Big Five personality traits,

along with values such as collectivism and individualism, were distal antecedents to

MTL, working primarily through an individual’s LSE. Building on the work of Bandura

(1986, 1997), LSE takes into account the experiential nature of leadership. Both positive

and negative leadership experiences provide a learning opportunity for the leader.

Positive leadership experiences help to reinforce the individual’s notion that he or she can

and should continue to lead, raising one’s LSE, which acts as a more proximal antecedent

to MTL. Conversely, negative leadership experiences can be deflating and may cause one

to question his or her leadership abilities. Thus, MTL is composed of more stable distal

antecedents including personality and values, which impact the more proximal and

somewhat fluid construct of LSE.

Chan and Drasgow (2001), borrowing from Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) theory of

reasoned action and Triandis’ (1980) theory of interpersonal behavior, reasoned that

MTL would best be conceptualized as a three dimensional construct comprised of

5

valences associated with the act of engaging in leadership, beliefs about outcomes of

enacting leadership behavior, and social norms regarding leadership. Similar to Myer and

Allen’s (1991, 1997) three component model of organizational commitment, Chan and

Drasgow proposed and showed through factor analytic techniques that MTL is comprised

of an affective-identity component (people lead because they want to), a noncalculative

component (people lead because there is no reason not to), and a social normative

component (people lead because it is the right thing to do). Their factor analysis on the

MTL items showed that the three factor model was indeed the better fitting model when

compared to the single factor unidimensional model.

Affective-identity MTL stems from people’s willingness to lead because of their

attitudes or affect related to leadership. When presented with the opportunity to take on

leadership roles, people who are high on affective-identity MTL assess the affective

result of taking on the leadership role. In essence, the question asked when deciding to

take on a leadership role is one of, “will this new role make me happy?” As outlined in

Chan (1999), affective-identity motivation is akin to the attitude component of Fishbein

and Ajzen’s (1975) theory of reasoned action or the affect component of Triandis’ (1977,

1980) theory of interpersonal behavior.

Social-normative MTL stems from people’s willingness to lead because of a sense

of duty or responsibility related to leadership. When presented with the opportunity to

take on leadership roles, people who are high on social-normative MTL rely on their

cultural or organizational norms with regard to leadership, and choose to lead based on

those norms. In cultures and organizations where being a leader is seen as honorable and

favored, those directed by social-normative MTL will take on leadership positions;

6

whereas in cultures and organizations were being a leader is seen in a less favorable light,

those directed by social-normative MTL will shy away from leadership roles. This social-

normative component of MTL is akin to the social norms component in the theory of

reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and the theory of interpersonal behavior

(Triandis, 1977, 1980).

Noncalculative MTL stems from a conscious evaluative process of determining

the rewards and consequences of taking on a leadership role. Noncalculative MTL can be

considered as a reverse formulation of a traditional outcome based motivation, whereby

individuals do not consider the economic gain of leading, but rather the economic loss

associated with taking on the added responsibility of leadership. Regardless, the

noncalculative component of MTL is economic in nature despite the framing of the

dimension in terms of absence of economic consideration. When presented with the

opportunity to take on leadership roles, people who are low on noncalculative MTL (and

are thus, calculative, when it comes to leadership) assess the potential rewards of

leadership (i.e., increased status, increased wealth, ability to make a difference) and

weigh those rewards against the potential costs (i.e., increased risk, increased

responsibility, potential for damaged relationships). This noncalculative component is

akin to the cognitive evaluation component present in Triandis’s (1977, 1980) theory of

interpersonal behavior. Those who are high in noncalculative MTL are not swayed by

economic gains or costs associated with leadership.

While Chan (1999) does not specifically hypothesize differential antecedents to

the three components of MTL, he notes the similarities to Meyer and Allen’s (1991)

commitment model. Chan also notes their argument that (1) affective commitment is a

7

direct result of experience and personal characteristics; (2) normative commitment is a

result of socialization practices at the cultural, familial, and organizational levels; and, (3)

continuance commitment is a result of one’s investment in the job or organization. With

regard to MTL, similar arguments should hold true. Affective-identity MTL is likely

most impacted by people’s experiences and personal characteristics. Social normative

MTL is likely a result of socialization practices at the cultural, familial and organizational

levels. While noncalculative MTL does not cleanly parallel continuance commitment, it

is expected that organizational factors (e.g., benefits, workload, etc.) for those in

leadership positions will drive noncalculative MTL.

Antecedents of MTL

Chan and Drasgow (2001) point out the importance of identifying the antecedent

variables that shape MTL in coming to a complete understanding of the construct and

how it operates. They outlined and tested five potential antecedents to MTL: general

cognitive ability, personality, values, LSE, and past leadership experience. Their findings

did not support general cognitive ability as an antecedent to MTL, but they did support

the other proposed relationships described below.

Personality traits. Chan and Drasgow (2001) discuss that the “personality trait

approach to leadership has, to a large extent equated personality traits with MTL.” Chan

(1999) points to reviews by Barrick and Mount (1991) and Hough (1992) that concluded

that personality variables were significantly related to managerial performance which can

be considered a proxy for leader performance. Given these findings, Chan and Drasgow

(2001) proposed personality traits as a distal antecedent to MTL, and tested their

hypothesis using hierarchical regression with the Big-Five personality dimensions and

8

their newly developed MTL measure. They found evidence for direct positive

relationships between extraversion with affective-identity MTL (ß = .24, p < .001,

R2=.61) agreeableness (ß = .18, p < .001, R2=.35) and emotional stability (ß = .11, p <

.001, R2=.35) with noncalculative MTL, and conscientiousness (ß = .14, p < .001, R2=.36)

agreeableness (ß = .15, p < .001, R2=.36) and extraversion (ß = .10, p < .01, R2=.36) with

social-normative MTL. Taken together, their findings support personality as a distal

antecedent to MTL.

Cultural values. Chan and Drasgow (2001) expanded their conceptualization of

distal antecedents of MTL from individual difference traits (i.e., personality and ability)

to include cultural determinants as predictors of MTL. They proposed that people’s

values would also serve as distal antecedents to MTL. Adopting Triandis’s (1995, 1998)

two dimensional conceptualization of culture, with a dimension representing

individualistic versus collectivistic orientation and a dimension representing vertical or

hierarchical versus horizontal orientation, they again tested their hypothesis using

hierarchical regression. They found evidence for a direct positive relationship between

vertical individualism (i.e., valuing personal achievement and competition) and affective-

identity MTL (ß = .12, p < .001, R2=.61). With regard to noncalculative MTL, they found

collectivist values (both vertical and horizontal) were positively related (ß = .23 and .09,

p < .01, R2=.35) and individualist values (again both vertical and horizontal) were

negatively related (ß = -.18 and -.09, p < .01, R2=.35). Finally, social-normative MTL

was positively related to vertical or hierarchical values (both individualist and

collectivist) (ß = .11 and .17, p < .001, R2=.36) and negatively related to horizontal

9

collectivism (i.e., valuing harmony and equality) (ß = -.11, p < .001, R2=.35). Taken

together, these finding suggests cultural values act as distal antecedents to MTL.

LSE. A more proximal antecedent to MTL proposed by Chan and Drasgow (2001)

is the concept of self-efficacy, or more specifically LSE. Self-efficacy is “the belief in

one’s capabilities to organize and execute the course of action required to manage

prospective situations” (Bandura, 1995, p. 2). LSE refers to the belief in one’s abilities to

function effectively and overcome obstacles in leadership roles. Given the widespread

consistent support of self-efficacy as a cognitive determinant of behavior (Stajkovic &

Luthans, 1998), they hypothesized LSE as a proximal antecedent to MTL. Using the

same analysis, they found that LSE was positively related to both affective-identity MTL

(ß = .40, p < .001, R2=.61) and social-normative MTL (ß = .17, p < .001, R2=.36), but was

not related to noncalculative MTL.

Past leadership experience. Finally, Chan and Drasgow (2001) proposed past

leadership experience as a semi-distal antecedent to MTL. They considered this semi-

distal in that it is more proximal than personality and values, but can have an impact on

LSE as a feedback loop and thus is not as proximal as LSE. Citing Fiedler and Garcia’s

(1987) cognitive resource theory of leadership which suggests that a leader’s past work

experience can have a significant impact on the performance of a leader and of his or her

group, Chan and Drasgow (2001) hypothesized that the quality and quantity of past

leadership experience has a direct path to MTL. Similar to the findings with LSE, past

leadership experience was only found to be positively related to affective-identity (ß =

.25, p < .001, R2=.61) and social-normative MTL (ß = .15, p < .001, R2=.36) and not to

noncalculative MTL.

10

LSE as a mediator between distal antecedents and MTL. In addition to the direct

paths proposed by Chan and Drasgow (2001) from both distal and proximal antecedents

of MTL, they also proposed indirect paths through LSE. Social cognitive beliefs, in this

case LSE or belief in one’s ability to lead, can be treated as more proximal explanations

of individual traits (Langston & Sykes, 1997). While they did not propose specific cases

of LSE mediating relationships between specific distal antecedents and the components

of MTL, they hypothesized the potential for mediation in the model. The results of their

studies suggested these indirect mediation paths existed between the distal antecedents of

extraversion, conscientiousness, and past leadership experience, and the affective-identity

and social-normative components of MTL. In addition, LSE mediated the relationship

between openness to experience and affective-identity MTL.

Observed leadership as a proposed new antecedent to MTL. Along with the

antecedents mentioned above and proposed by Chan and Drasgow (2001), it appears

possible that, in addition to LSE achieved through personal leadership successes and

failures, an individual may indeed also be impacted through an observational mechanism.

This observational mechanism could result from the positive experiences of having a high

quality relationship with an effective leader. Individuals not only learn through the

experiences of their own successes and failures, but they also learn through the successes

and failures of those around them, particularly those they regard as role models. In the

context of leadership, one’s direct supervisor serves as a primary role model with regard

to leadership behavior. Given the strong emphasis placed on LSE in the understanding of

MTL, it seems appropriate to further investigate additional means by which LSE is

developed and maintained. Research investigating the “cascading effect” of leadership

11

(Bass, Waldman, Avolio, & Webb, 1987) can be applied to MTL to provide further

explanation of how this motivation develops and is nurtured.

The Cascading Effect of Leadership

At the heart of Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) MTL model is LSE, or the belief that

one can enact the behaviors to succeed in a leadership role. This concept of self-efficacy

lies at the heart of Bandura’s (1986) social learning theory. According to Bandura, self-

efficacy can arise through four mechanisms: mastery experiences, social modeling, social

persuasion, and psychological responses. First, people can develop self-efficacy through

mastery experiences or through their own successful performance of tasks, and,

conversely, self-efficacy may be diminished following failed experiences. Second,

individuals can develop self-efficacy through social modeling or through the observation

of other people’s success in completing tasks. Third, people can develop self-efficacy

through social persuasion, or through positive reinforcement from others that one can

succeed at completing the task. Finally, self-efficacy can be shaped through an

individual’s psychological responses to situations. Feelings of stress or nervousness may

serve to diminish one’s self-efficacy, whereas feelings of excitement or anticipation may

boost one’s self-efficacy.

Chan and Drasgow’s model of MTL focuses primarily on mastery experience and

its impact on LSE. Their model reflects the feedback process of taking part in leadership

experiences, and the impact those experiences have on LSE and motivation to take on

additional leadership roles. Mastery experiences may be a primary mechanism in the

development of LSE and MTL. However, when direct leadership experience is limited or

12

absent, it seems important to consider additional mechanisms from which LSE can arise.

The observational mechanism proposed by social learning theory is a plausible candidate.

In addition to building LSE through direct behavior and reinforcement following

the mastery path, individuals can learn leadership behavior and develop LSE through the

observations of the behaviors of others. While the observed role model can certainly be

anyone in an individual’s life, one’s immediate supervisor will serve as a direct and

salient role model for leadership behavior. The notion that an immediate supervisor can

serve as a role model is supported by previous research (e.g., Gerstner & Day, 1997; Lord

& Brown, 2004) which proposed that work supervisors and their behaviors are salient

cues for followers in organizations.

Existing leadership research has focused on the direct supervisor as a role model

for followers. For example, Bass, Waldmen, Avolio, and Bebb (1987) investigated the

“cascading effect” of transformational leadership. Specifically, they found that

transformational leadership behaviors cascaded like “falling dominoes” where

transformational behaviors displayed at higher levels of management are similarly

displayed at lower levels of management. Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, and

Salvador (2009) also looked at this cascading effect in the context of ethical leadership,

its impact on followers’ counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs), and organizational

citizenship behaviors (OCBs). Mayer et al., found that ethical behaviors performed by

upper-level management were related to the performance of CWBs (ß = -.31, p < .001)

and OCBs by the followers of upper-level managers (ß = .44, p < .001). The effects of

upper-level managers’ ethical behaviors on followers’ CWB and OCB were mediated by

supervisory ethical leadership. The authors suggest that social learning theory is a “useful

13

theoretical lens” through which to view their results in the passing down of ethical

behaviors. Both studies suggest a modeling or observational process by which individuals

observe the behaviors of their direct supervisors, and that, in turn, lead to a change in

behavior of the individuals.

It is expected that, in addition to gaining LSE and MTL by having positive

leadership experiences as currently represented in Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) model

(see Figure 1),1 there is also an observational mechanism to developing and maintaining

LSE and MTL whereby individuals observe successful leadership others. In short, it is

expected that having a high quality, close relationship with a direct supervisor who is

perceived to be an effective leader will result in increased LSE and MTL. In order to

fully formulate this hypothesis, it is important to first consider the importance of having a

high quality leader.

Figure 1 – Portion of Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) MTL model

1 Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) model of MTL is more expansive and includes cognitive ability and domain specific knowledge as additional precursors to leadership performance. In addition, the concept of leader performance is presented in the context of acquiring the skills and experiences needed to be a successful leader. This is different from leader performance conceptualized as leader effectiveness, which is the approach this research agenda takes.

14

Relationship of Observed Leadership with MTL

As previously stated, it is expected that in addition to the traditional leadership

mastery path whereby direct leadership experience leads to an increase in LSE and MTL,

there is also an observational mechanism at work whereby LSE and MTL can be

impacted by experiencing the positive leadership of others, specifically one’s direct

supervisor. Bandura (1986, 1988) discusses two means by which social modeling can

affect people’s self-efficacy. First, an effective model displays beneficial strategies for

managing difficult situations. Having knowledge of alternative and effective strategies

builds one’s confidence that he or she can perform in similar difficult situations. Second,

self-efficacy beliefs are impacted through the social comparison process whereby

observing similar individuals succeed in their endeavors helps to raise one’s belief that he

or she can succeed in similar endeavors. Certainly, if the skill level of the observer and

the model are vastly different, this social comparison may be de-motivating or

detrimental to one’s self-efficacy. However, in an organizational context where the skill

level and backgrounds of direct supervisors and followers are often not so disparate, this

social comparison is expected to be self-efficacy enhancing in nature. Interacting with a

supervisor that effectively displays leadership behaviors will serve as a role model for

enacting similar leadership behaviors, and serve to increase one’s confidence in

successfully engaging in those behaviors. This leads to the following hypothesis

regarding leader effectiveness and LSE:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ perceptions of their direct supervisor’s leadership

effectiveness will be positively related to their own LSE.

15

Similarly it is expected that this observational mechanism will have an impact on

an individual’s MTL, and that this impact will be different depending on the component

of MTL. Given the similarities between the three component model of commitment

(Meyer & Allen, 1987, 1991) and the three component conceptualization of MTL, a

similar pattern of antecedents is expected. Allen and Meyer (1990) argued and provided

evidence that affective commitment was a direct consequence of work experiences and

personal characteristics. As previously stated, the behaviors supervisors enact are salient

organizational cues. Perceiving one’s supervisor as effective is a positive work

experience in the realm of leadership that will serve to enhance the affective-identity

component of MTL. This is similar to the way that positive work experiences enhance

affective commitment to one’s organization. Allen and Meyer argued that the normative

component of commitment was driven by an individual’s socialization experiences

(familial and cultural factors) and his or her experiences within the organization.

Interaction with, and observation of, one’s supervisor is a key component of that

organizational socialization. In essence, observing this positive behavior in one’s

supervisor serves to establish and/or reinforce the organizational norms associated with

being a successful leader, which serves as an antecedent to the social-normative

component of MTL. Finally, Allen and Meyer argue that the antecedents to continuance

commitment are rooted in the economic evaluation of investments and alternatives. While

it is certainly possible that one may observe the rewards and consequences of effective or

ineffective leadership from one’s direct supervisor, the contingencies are set at the

organizational level regardless of the perceptions of one’s supervisor’s effectiveness. The

economic incentives or consequences related to taking on a leadership position are

16

largely driven by the organizational context and not by the perceived effectiveness of

one’s supervisor. Some organizations may be very good at rewarding effective leadership

and punishing ineffective leadership, while other organizations may not be as successful.

The economic evaluation has less to do with the effectiveness of one’s leader and more to

do with the contingencies put into place by one’s organization, and the individual’s

orientation toward external rewards as a motivator. This leads to the following

hypotheses regarding leader effectiveness and MTL:

Hypothesis 2a: Employees’ perceptions of their direct supervisor’s leadership

effectiveness will be positively related to their own affective-identity MTL.

Hypothesis 2b: Employees’ perceptions of their direct supervisor’s leadership

effectiveness will be positively related to their own social-normative MTL.

Leader Member Exchange (LMX)

To this point, the discussion of developing LSE and MTL by observing one’s

direct supervisor has been limited strictly to the behaviors or perceived leadership

effectiveness of the supervisor. If subordinates perceive that their supervisors are

effective, it was hypothesized that this has a positive relationship with followers’ LSE

and MTL. When considering this observational mechanism, it is important to not just

consider the perceived effectiveness of the supervisors, but also the quality of the

supervisor. One supervisor may oversee several individuals and may have very different

relationships with each subordinate. It is expected that the benefits of observing an

effective supervisor will be stronger in a closer more meaningful relationship than it will

in a more distant, detached relationship. While much of leadership research is focused on

characteristics of the leader or the situational constraints placed on the leader, leader

17

member exchange (LMX) focuses the lens on the quality of the relationship between the

leader and the follower.

LMX has become a popular leadership theory in the past 30 years due to its

hypothesized relationships between leader processes and leader outcomes (Gerstner &

Day, 1997). At the time of its inception in the early 1970s by Graen and colleagues

(Dansereau, Cashman & Graen, 1973; Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Graen, 1976;

Graen & Cashman, 1975), LMX represented a break from the more traditional leadership

research that focused on the characteristics of the leader or on the constraints of the

situation. Instead, LMX was one of the first leadership theories to focus on the

relationship element of leadership and the fact that all leadership relationships are not

created equal. The same leader may have very different relationships with each of the

individuals with whom he or she interacts. LMX also takes into account the evolutionary

nature of the leader follower relationship in that relationship trust is fostered over time.

The leader follower relationship evolves over time (Graen, 1976) with mutually

beneficial exchanges resulting in more mature developed relationships. While LMX is

likely related to perceptions of leader effectiveness, LMX is a distinct construct.

The research on LMX generally supports a positive relationship among LMX

quality, performance, and attitudinal outcomes, especially with regard to the follower

(Gerstner & Day, 1997). In their meta-analysis of LMX, Gerstner and Day (1997)

enumerate the research findings regarding the positive outcomes associated with LMX:

high performance ratings (e.g., Liden, Wayne, & Stilwell, 1993), better objective

performance (e.g., Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982; Vecchio & Gobdel, 1984),

higher overall satisfaction (e.g., Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982), greater

18

satisfaction with supervisor (e.g., Duchon, Green & Taber, 1986), stronger organizational

commitment (e.g., Nystron, 1990), and more positive role perceptions (e.g., Snyder &

Bruning, 1995). Their meta-analytic findings support the positive relationship between

LMX relationship quality and follower outcomes.

It is expected that the quality of the LMX relationship will have an impact on the

observational mechanism discussed above and outlined in Hypotheses 1 and 2. LMX

quality will moderate the strength of the relationships described above, such that

followers with stronger LMX relationships will experience a greater impact of leader

effectiveness on their LSE and MTL. With regard to LSE, having an effective leader can

impact follower effectiveness via two mechanisms: observing effective strategies, and

social comparisons to similar others. In both cases, a closer relationship is likely to

enhance the positive effects of leader effectiveness on the LSE of the follower. Having a

closer relationship will result in increased interactions, and concomitantly, increase the

likelihood of observing effective strategies for dealing with difficult situations. A closer

relationship will also facilitate the observational mechanism by increasing perceptions of

similarity, and by increasing the opportunity to observe leadership successes. This leads

to the following hypothesis regarding the moderating role of LMX on the relationship

between leader effectiveness and follower LSE.

Hypothesis 3: Leader member exchange (LMX) will moderate the positive

relationship between perceived supervisors’ leadership effectiveness and

subordinates’ LSE, such that the relationship will be stronger when the quality of

LMX is high versus low.

19

Similarly it is expected that high quality LMX will have an enhancing effect on

follower MTL. In the case of both affective-identity MTL and social-normative MTL, it

was proposed that effective leadership was a salient organization cue. With regard to

affective-identity MTL, the effective leader serves to create positive experiences for the

follower. Having a high quality relationship with one’s supervisor increases the

likelihood of experiencing these effective leader behaviors and the likelihood of the

follower perceiving these interactions as positive experiences. With regard to social-

normative MTL, the effective leader serves as a model of the organizational norms

related to leadership. Having a high quality relationship with one’s supervisor increases

the likelihood of observing the effective leader and the likelihood of interpreting the

effective leader’s behaviors as norms representing the organization. This leads to the

following hypotheses regarding the moderating role of LMX on the relationships between

leader effectiveness and follower MTL.

Hypothesis 4a: Leader member exchange (LMX) will moderate the positive

relationship between perceived supervisors’ leadership effectiveness and

subordinates’ affective-identity MTL, such that the relationship will be stronger

when the quality of LMX is high versus low.

Hypothesis 4b: Leader member exchange (LMX) will moderate the positive

relationship between perceived supervisors’ leadership effectiveness and

subordinates’ social-normative MTL, such that the relationship will be stronger

when the quality of LMX is high versus low.

20

A Competency Based View of Leadership Effectiveness

One difficulty in studying leadership is pinpointing the criteria for measuring

successful leadership. In an applied context, a proxy for successful leadership may be the

effectiveness of the group one is leading. However, this is obviously confounded with a

number of factors related to the skill and ability of team members. In short, a poorly led

group of individuals may be very successful, and, conversely, an extremely well-led

group may flounder. In general, the study of leadership separates performance criteria

into two categories: leader effectiveness and leader emergence (Lord et al., 1986). As

noted by Judge, Bono, Ilies, and Gerhardt (2002) leader emergence is more of an

assessment of who is leader-like, and is generally an assessment made by individuals who

have limited information regarding leader performance. Leader emergence is often used

as a leader criteria in experimental settings just for that reason, as individuals are often

working in low fidelity leader simulations where limited performance information is

present and a more heuristic assessment of who is leader-like is an appropriate leader

criteria. Leadership effectiveness, however, is less focused on perceptions of leadership

but is focused, rather, on the observable behaviors enacted by the leader toward the goal

of influencing or guiding the group’s activities toward a successful end (Judge et al.,

2002). In the context of real world applied research consisting of long-term established

relationships, which is the case with MTL research, it would seem that a behavioral

leadership effectiveness approach is appropriate for understanding leadership

performance and assessing success as a leader.

Over the last 20 years, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management has conducted

extensive research identifying the competencies related to successful leadership in the

21

federal government context (Hillery et al., 2003). These competencies encompass the

specific leadership behaviors that can be used to evaluate leadership success. Rooted in

the framework identified by Howard and Bray’s (1988) study of successful managerial

performance at AT&T, Corts and Gowing (1992) identified 26 primary and 10 ancillary

dimensions of leadership. These dimensions served as the bases for Gregory and Park’s

(1992) study of leadership effectiveness. They surveyed nearly 8,000 federal executives,

managers and supervisors, eliciting the importance of each competency toward effective

job performance in a leadership position. The resulting leadership competency model was

later updated, leveraging a study conducted by Eyde et al. (1999), in which subject matter

experts participated in focus groups to discuss the behaviors related to effective

managerial performance. The resulting competency model is comprised of 28 leadership

competencies consisting of behaviors that are related to leadership effectiveness at all

levels of supervision. These competencies and their definitions are listed in Appendix A.

The OPM Leadership Competency Model represents an exhaustive categorization of

leadership behaviors that are exhibited across the entire range of job roles in the federal

government. Since many of these competencies are only required in specific job roles,

only those competencies that are universal in nature will be used for the purposes of

hypothesis testing. The following 13 competencies will be used to evaluate leadership

effectiveness: accountability, conflict management, creativity and innovation,

decisiveness, developing others, flexibility, integrity and honesty, interpersonal skills,

oral communication, problem solving, resilience, team building, and written

communication.

22

Relationship of MTL to Leadership Criteria

In addition to investigating the observational mechanism for enhancing self-

efficacy and MTL, it is important to continue to assess the outcomes associated with a

motivated leader. To this point, relatively little research has investigated the positive or

negative consequences of having a strong MTL. It would certainly seem intuitive that a

motivated individual who has the requisite abilities to perform as a leader will be more

successful as compared to someone who lacks that motivation. But as discussed earlier,

the criteria for successful leadership is not always clear cut.

Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) conceptualization of MTL as it relates to leadership

outcomes was more focused on behavioral indicators of leadership potential rather than

behavioral indicators of leadership success. Their model was more focused on proximal

criteria related to MTL, such as an individual’s willingness to take on leadership training

or leadership positions. Their research, however, did not address the likelihood of success

in those leadership roles as a function of MTL. While they did address leadership

potential, which is more reflective of leader emergence than leader success, the more

distal outcome of MTL, actual success as a leader, was not examined. In their sample of

Singaporean military students, leadership potential ratings were collected from a panel of

raters as part of a three-day assessment center during the cadets’ basic training, and again

were collected from their direct supervisor at the end of the three-month basic training.

The assessment center was part of the cadets’ officer selection system, and as such,

represented a test of maximal performance. The supervisory assessment at the completion

of basic training covered the entire three-month period, and as such, represented a test of

typical performance.

23

Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) findings were consistent across the two measures of

leadership potential. In both the assessment center rating representing maximal

performance and the overall rating of performance in the basic training representing

typical performance, MTL added significant incremental validity in the prediction of

leadership potential above that of other measures such as cognitive ability, past

leadership experience, LSE, and personality variables ( R2 ranging from .01 to .16).

Looking at the three components of MTL separately, they found that affective MTL and

noncalculative MTL were both significantly predictive of leadership potential rating

above cognitive ability in both scenarios (assessment center and overall basic training

rating) with ß ranging from .08 to .13, p < .05. Social-normative MTL did correlate with

the leadership potential criterion in the expected direction, but did not contribute unique

variance to its prediction given the other predictors. Chan and Drasgow (2001) explain

these findings by stating that observers find individuals that enjoy leading, or that lead

with little concern for reward, to have more leadership potential. They state that “merely

having a sense of duty or social obligation to lead may be insufficient to convince others

that one has the potential to lead” (Chan & Drasgow, 2001; p. 494).

While this study provides some predictive validity evidence for MTL, the specific

nature of the sample (Singaporean military students), and the limited scope of the criteria

(leadership potential ratings as opposed to a more robust assessment of actual leadership

skill or behavior), necessitate more investigation into the predictive validity of MTL.

Hendricks and Payne (2007), in their study of goal orientation and leadership

effectiveness, extended the research on the relationship of MTL to leadership outcomes.

They investigated goal orientation, MTL, and leadership effectiveness in a lab setting

24

with teams of four undergraduates completing an experimental task involving building

products and maximizing their profits. One of the four individuals was randomly

assigned to act as the team leader in the task. They utilized two measures of leadership

effectiveness. First, team members assessed the leaders’ overall effectiveness and a

consensus score was calculated across the three rating members. Second, an objective

assessment of task success was used (overall profits in the experimental task). They

hypothesized positive relationships between each form of MTL and leader effectiveness.

Consistent with their hypotheses and with the findings of Chan and Drasgow (2001),

there was a significant and positive relationship between noncalculative MTL and

leadership effectiveness, as measured by the subjective assessment by team members of

leader effectiveness (ß = .23, p < .05). While not significant, the authors characterize the

relationship between affective MTL and subjective ratings of leader effectiveness as

approaching significance. Surprisingly, while not significant, the relationship between

social-normative MTL and subjective assessments of leadership effectiveness was

negative, such that those who were high in social normative MTL received lower

leadership effectiveness ratings. There were no significant relationships between

measures of MTL and the objective performance of groups on the experimental task.

While Hendricks and Payne’s (2007) study provides preliminary evidence

regarding the relationship between MTL and leader effectiveness, the low fidelity and

contrived nature of their experiment involving undergraduate students may not generalize

to work settings. To truly understand effective leadership and the effects of MTL on the

specific leadership behaviors that relate to effective leadership, a more ecologically valid

assessment of leadership in a field setting is in order. While the research on the

25

relationship between MTL and leadership outcomes is scant, in both cases (Chan &

Drasgow, 2001, with their assessment of the leadership outcome of leader potential and

Hendricks & Payne, 2007, with their assessment of the leadership outcome of leader

effectiveness), positive relationships were hypothesized between each component of

MTL and the leadership outcome. The surprising findings with regard to social-normative

MTL and leader outcomes could be a function of the subjective assessments involved

with both studies. In the case of Chan and Drasgow (2001), the assessments were of

leader potential which would not necessarily relate to leader effectiveness. In the case of

Hendricks and Payne (2007), the assessments were of leader effectiveness in a very

limited exercise, where perceptions of personality and leadership style may have colored

the assessment of effectiveness beyond the actual leadership skills being displayed.

A potential explanation for the past findings with regard to the link between the

various components of MTL and job performance may lie in the tenets of self

determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), and the differential motivational power of

intrinsic versus extrinsic motivators. Self determination theory distinguishes between

autonomous motivation and controlled motivation, with a continuum ranging from purely

autonomous motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation or doing something because one wants

to and derives pleasure and interest by doing so) to strictly controlled (i.e., extrinsic

motivation arising from contingent rewards or doing something because doing so will

result in money). Placing the three components of MTL along this continuum can shed

light on their relation to overall leadership performance, and potentially explain the past

research findings. Affective-identity MTL is clearly autonomous in nature and is the

intrinsic motivation because one enjoys leading. Noncalculative MTL is focused on the

26

rewards and/or lack of consequences associated with leadership, and is, therefore

controlled in nature. Social-normative MTL is not as easy to classify, but given the self-

determination continuum (Gagne & Deci, 2005), it appears that norms would be

considered introjected regulation, which is slightly more autonomous than purely

controlled external motivation, but still more on the controlled end of the continuum.

According to cognitive evaluation theory (Deci, 1971; Deci & Ryan, 1980), extrinsic

rewards can serve to reduce feelings of autonomy and thus undermine intrinsic

motivation. Given that affective-identity MTL is more related to intrinsic motivation, and

social-normative and noncalculative motivations to lead are more related to extrinsic

motivation, it is expected that affective-identity MTL will have a stronger relationship to

leader performance than social-normative and noncalculative MTL.

Given the previous research linking MTL with leader effectiveness and the

theoretical explanations provided above, this study will further investigate the following

hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5a: Employees’ affective-identity MTL will be positively related to

their leadership effectiveness.

Hypothesis 5b: Employees’ social-normative MTL will be positively related to

their leadership effectiveness.

Hypothesis 5c: Employees’ noncalculative MTL will be positively related to their

leadership effectiveness.

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between MTL and leadership effectiveness will be

strongest for affective-identity MTL.

27

Summary of Proposed Study

This dissertation will further the extant research on the construct of MTL. What

little research there is on MTL has, to date, investigated the measurement and antecedents

of MTL. The primary method of developing MTL is through mastery in leadership

experiences and training, which serves as a feedback loop fostering stronger LSE and

increased MTL. This dissertation will investigate a secondary method, which involves

observing and enacting the effective leadership behaviors experienced through a role

model in a high quality leader-follower relationship. This research will also advance the

understanding of the outcomes associated with MTL by focusing on the impact of MTL

on individual leader effectiveness. To date, the little research regarding MTL and

outcomes has been focused on leader emergence or subjective assessments of leader

potential. This research will serve as a first investigation into the impact of MTL on

leader effectiveness measured using 360 ratings on key leadership behaviors.

28

Chapter 2: Method

Participants

360 participants. Employees already participating in the U.S. Office of Personnel

Management’s Leadership 360 were asked to participate in this study. Their participation

was completely voluntary and they were informed that any additional data collected for

the purposes of this study would not be shared with anyone from their organization. Data

were collected from 226 individuals.

360 raters. Those participating in the OPM Leadership 360 assessment solicited

ratings from workers whom they consider to be their supervisor, peers and subordinates.

There were no added measures for individuals providing ratings, and as such, the 360

assessment procedure for raters remained identical to any other leadership 360

assessment conducted by OPM.

Measures

MTL. Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) 27 item Likert based scale was used to measure

MTL. In their initial study utilizing three samples, the scales, consisting of 9 items

measuring each of the three MTL dimensions (affective-identity, social-normative, and

noncalculative) showed relatively high internal consistency with as ranging from .91 to

.94 for affective-identity MTL, .80 to .84 for noncalculative MTL, and .65 to .75 for

social-normative MTL. Coefficient alphas for the current study can be found in Table 1.

A list of items can be found in Appendix C.

29

LSE. Paglis and Green’s (2002) LSE scale was used. The scale consists of 12

items, with 4 items measuring self-efficacy with regard to setting group direction, 4 items

measuring self-efficacy with regard to gaining group member commitment, and 4 items

measuring self-efficacy with regard to overcoming obstacles. Reliability of the three LSE

sub-scales ranges from a = .86 to .92 with a total LSE scale reliability of a = .92. The

coefficient alpha for the current study can be found in Table 1. A list of items can be

found in Appendix C.

LMX. The LMX-7 (Graen et al., 1982) was used to assess follower perceptions of

the LMX relationship. Previous research has suggested that the LMX-7 provides the

soundest psychometric properties of available LMX measures (Gerstner & Day, 1997). In

their meta-analysis, Gerstner and Day (1997) reported a mean alpha of .89 for this

measure. The coefficient alpha for the current study can be found in Table 1. A list of

items can be found in Appendix C.

Leadership competencies. The United States Office of Personnel Management’s

Leadership 360 assessment was used to collect participant leadership performance

criteria. OPM’s Leadership 360 is a multi-source rating device created to assess OPM’s

Leadership Model which was first developed in the early 1990s (Corts and Gowing,

1992), leveraging the framework from Howard and Bray’s (1988) seminal study of

dimensions of successful managerial performance at AT&T. This 100 item measure taps

into 28 leadership competencies and is administered to the participants, their direct

supervisor, self-identified peers, and self-identified subordinates. Competency scores are

calculated using a weighted average in which each supervisory ratings receive 1/3 of the

weighting toward the all-rater score, the average of all peer ratings receive 1/3 of the

30

weighting toward the all-rater score, and the average of all subordinate ratings receive 1/3

of the weighting toward the all-rater score. The OPM Leadership 360 is administered as a

strictly developmental assessment, and the individual results were only shared with the

participant receiving the assessment. The developmental nature of the OPM Leadership

360 reduces the likelihood of participants selecting raters that will inflate their ratings,

and increases the likelihood of raters providing frank and honest ratings. The OPM

Leadership 360 has been administered to over 17,000 participants with over 162,000 total

ratings. Coefficient alphas for the 28 leadership competencies range from .78 to .96

(Hillery et al., 2003). Coefficient alphas for the 28 competencies, broken out by rating

source for the current study, can be found in Table 2. A listing of the 28 leadership

competencies and their corresponding definitions can be found in Appendix A. A list of

items can be found in Appendix B.

Perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness. Participants were asked to

complete a partial leadership competency assessment for their direct supervisor (the

individuals they self-identified to complete the leadership portion of their 360

assessment). Only the 13 competencies identified as being universal in their value to

assessments of leadership were rated in order to minimize the additional burden on those

participating in the assessment. In addition, to minimize survey length single item

measures were administered for each competency, and the respondents were asked to rate

their supervisors overall effectiveness from very ineffective to very effective for each

competency. The 13 item measure of perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness on the

competencies was aggregated to produce a single overall rating of perceived supervisor

31

leadership effectiveness. The coefficient alpha for this scale can be found in Table 1. A

list of items can be found in Appendix C.

Control variables. Given the importance of past leadership experience as an

antecedent of LSE and MTL, it is important to control for past leadership experience

when testing the unique contribution of the effects of LMX and perceived supervisor

leadership effectiveness on follower LSE and MTL. A single item measure asking

participants to indicate how long they have been in a formal leadership position was used.

Procedure

Since this study leverages the existing OPM Leadership 360 process, the

procedure for conducting this research followed closely to the existing process for

administering the assessment. Participants were generally recruited by their agency to

participate in the leadership 360 assessment as part of an agency-sponsored leadership

development class and were run through the assessment as a cohort. In some instances,

the 360 assessment was offered on a more ad hoc basis, and was not tied to a specific

agency-run course. Regardless of the context in which the leadership 360 assessment was

offered, the procedure for conducting the assessment was identical.

Once participants were identified by their agency to take part in a leadership 360,

a one hour 360 orientation session was delivered either in person or via teleconference.

During such a session, the purpose of 360 assessments was reviewed, the OPM

leadership model was outlined, the participants were instructed of their role in the process

of the assessment, and the participants were provided the opportunity to ask questions

regarding the assessment and process. In addition, participants were instructed about the

research portion related to this particular study and advised that their participation in the

32

research portion of the study was strictly voluntary. Shortly after the orientation session,

individuals were sent email notifications with instructions for launching the 360

assessment.

Participants thereafter received an email with instructions and a link for accessing

the 360 assessment secure survey website. Once logged into the site, participants

identified individuals for providing 360 leadership feedback. They were instructed to

enter the name, email address, and relationship type for their direct supervisor, and at

least 3 subordinates, and at least 3 peers and that all raters should be able to assess their

leadership capabilities. It was suggested that only individuals who have known the

participant for at least 6 months should be chosen to complete the assessment. Once

participants completed and saved their list of participants, they clicked a notification

button that generated and sent instruction emails to their identified raters. This officially

began the assessment period for the participant. The assessment period generally lasted

three to four weeks, with extensions as needed.

During the assessment period, participants completed their self assessments and

raters completed their assessments on the participants. All assessments were completed

online using the account access information provided in the notification emails. All

assessments were identical and included the 100 prescribed items (98 close-ended

behavioral frequency rating items and 2 open-ended items). After completing the required

self-assessment, participants were directed to the optional research only portion of the

assessment where they were provided with the additional measures (MTL, LMX, and

perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness).

33

Once the 360 assessment period was closed, individual reports were produced.

Before distributing reports, a one hour group feedback session was conducted either in

person or via teleconference to review the 360 process, discuss group trends and

comparisons to government-wide benchmarks, and explore the best approach for

understanding the data presented in the individual feedback reports. After the group

feedback session reports were either distributed personally or electronically via email.

Data Cleaning

Prior to any analysis, the data was cleaned of any and all identifying information

to preserve the confidentiality of those choosing to participate in the research portion of

the 360 assessment. In addition, only the assessments of participants who completed the

full research portion of the assessment, where they provided responses to the MTL, LMX

and perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness items, were included in the analysis. If

individual responses to a scale were omitted, then data was preserved. However if an

entire scale was left incomplete the scale score was not imputed. Less then 1% of all

possible responses were left blank.

Scoring

Scoring for the research only scales (MTL, LMX, perceived supervisor leadership

effectiveness, LSE) followed the standard practice of calculating a mean for all items on

the scale in question. For the perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness items, which

measure the 13 core competencies, averages were calculated for each competency and an

overall supervisory leadership effectiveness average was calculated based on the mean of

all competency scores.

34

Scoring of the 360 leadership assessment, which was used to determine an overall

participant leadership performance score and individual competency scores for each of

the 28 core competencies, followed the standard OPM scoring procedure. Competency

scores were calculated using a weighted mean approach such that the supervisory rating

was weighted 1/3, the peer rating was weighted 1/3 and the subordinate rating was

weighted 1/3. The ratings for each rating group were a simple average of the scores

across all raters averaged across all items for a given competency. Consistent with the

OPM 360 assessment scoring and existing research on 360 assessments (Conway &

Huffcutt, 1997; Harris & Schaubroeck, 1988; Attwater, 1988), the self-assessment was

not used in the calculation of the overall or individual competency scores as this rating

has been shown to be the least accurate. Harris and Schaubroeck (1988) found a high

correlation between supervisor and peer ratings (.62), while Conway and Huffcutt

extended these findings by suggesting that only self ratings are significantly divergent to

warrant exception. Atwater (1998) suggests the disparity in self versus other (supervisor,

peer, and subordinate) ratings are likely caused by biases that affect self-ratings. While

the self rating component of 360 assessment is a valuable self-reflection and voice

component in the assessment process, consensus suggests that aggregating scores across

rater groups excluding self ratings is the appropriate scoring approach (Anderson,

Krajewski, Goffin & Jackson, 2008).

In addition to calculating an overall leadership performance score averaging

across the 28 leadership competencies, the OPM Leadership 360 model provides for a

logical breakdown of the 28 leadership competencies into a conceptual framework of

fundamental competencies, and five additional logical groupings of competencies aligned

35

around the type of focus a leader’s position might require. This Executive Core

Qualification (ECQ) model categorizes the 28 leadership competencies according to the

type of leadership being enacted. This model is the foundation for selecting individuals

into leadership positions and for evaluating performance at the executive level. The ECQ

model breaks the 28 leadership competencies into the following leadership areas:

fundamental leadership competencies, competencies associated with leading change,

competencies associated with leading people, competencies associated with driving

results, competencies associated with business acumen, and competencies associated with

building coalitions. Classification of competencies into their ECQ groupings can be

found in Appendix A. ECQ scores were also calculated by averaging the component

competencies, and were used as more specific, targeted measures of leadership

performance.

36

Chapter 3: Results

A total of 225 individuals completed the supplemental leadership motives survey,

of which 220 had corresponding OPM Leadership 360 assessments. The sample was

predominantly female (60%), and fairly tenured with respect to leadership experience,

with 54% indicating at least 5 years of experience in leadership positions and less than

20% indicating no, or less than 1 year, of leadership experience. Descriptive statistics and

correlations for the study variables can be found in Table 1. A more comprehensive

review of the descriptive statistics for the OPM Leadership 360 assessment can be found

in Table 2. OPM Leadership 360 ratings were provided by 2370 individuals, yielding an

average of 10.8 raters per participant (1 self, 1.1 supervisors, 4.4 peers, and 4.2

subordinates). Intercorrelations of the overall subjective ratings of performance for the 4

rater groups can be found in Table 3. While the self ratings did not correlate with peer

and subordinate ratings, the three other rating groups (supervisor, peers and subordinates)

did correlate significantly with each other. Consistent with Oh and Berry (2009),

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for the peer and subordinate

groups, with an average ICC of .36 and .30 respectively. An ICC was calculated for each

participant for each rating group across the 98 rated behaviors. Minimum, maximum, and

mean ICC information for the two rating groups are found in Table 4. Given that the vast

majority of ratings for the supervisor group were provided by single individuals, no ICCs

were calculated for this group.

37

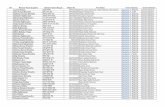

Table 1 – Study Variables, Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

Variable Mean SD N alpha 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1. Affective-identity MTL 3.73 0.50 225 0.74 --2. Social-normative MTL 3.61 0.48 225 0.76 0.25* --3. Noncalculative MTL 4.05 0.46 225 0.76 0.08 0.20* --4. Leadership experience 5.51 2.50 225 -- 0.21* 0.08 0.10 --5. LSE 9.15 0.98 225 0.94 0.16* 0.19* 0.26* 0.12 --6. LMX 3.95 0.74 225 0.90 -0.01 0.01 0.13 -0.08 0.21* --7. Percieved supervisor effectiveness 4.20 0.78 225 0.95 -0.10 0.03 0.14* -0.02 0.09 0.71* --8. Leadership performance 4.23 0.31 219 -- -0.08 -0.07 0.00 -0.01 0.08 0.20* 0.13 --9. ECQ - Fundamental competencies 4.34 0.31 218 -- -0.12 -0.14* 0.03 -0.09 0.05 0.23* 0.14* 0.88* --10. ECQ - Leading change 4.19 0.33 207 -- -0.07 -0.08 -0.01 -0.02 0.11 0.21* 0.13 0.94* 0.81* --11. ECQ - Leading people 4.20 0.46 216 -- -0.02 -0.04 -0.04 0.08 0.01 0.15* 0.10 0.70* 0.57* 0.60* --12. ECQ - Results driven 4.27 0.33 212 -- -0.06 -0.04 0.00 -0.05 0.07 0.14* 0.08 0.93* 0.77* 0.91* 0.47* --13. ECQ - Business accumen 4.18 0.36 178 -- -0.02 0.00 -0.03 0.07 0.08 0.11 0.02 0.90* 0.78* 0.84* 0.65* 0.88* --14. ECQ - Building coalitions 4.19 0.38 208 -- -0.07 -0.07 -0.02 -0.05 0.08 0.16* 0.09 0.88* 0.74* 0.85* 0.46* 0.86* 0.81*Note: '*' is significant p < .05. MTL = Motivation to Lead. LSE = Leadership Self Efficacy. LMX = Leader Member Exchange.

38

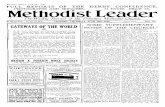

Competency Alpha Mean SD Alpha Mean SD Alpha Mean SD Alpha Mean SD Alpha Mean SDPublic Service Motivation 0.63 4.21 0.44 0.81 4.39 0.34 0.82 4.38 0.31 0.87 4.33 0.27 0.84 4.37 0.36Integrity/Honesty 0.77 4.56 0.34 0.86 4.63 0.24 0.89 4.55 0.24 0.91 4.40 0.30 0.90 4.53 0.35Interpersonal Skills 0.85 4.28 0.36 0.90 4.40 0.29 0.92 4.38 0.27 0.94 4.31 0.29 0.93 4.36 0.39Oral Communication 0.82 4.09 0.51 0.87 4.27 0.40 0.90 4.26 0.37 0.92 4.27 0.40 0.91 4.26 0.36Written Communication 0.89 4.11 0.22 0.92 4.15 0.17 0.94 4.30 0.14 0.94 4.34 0.16 0.94 4.27 0.41Continual Learning 0.69 4.10 0.49 0.77 4.38 0.30 0.80 4.38 0.28 0.85 4.33 0.28 0.82 4.37 0.36Creativity and Innovation 0.81 4.03 0.35 0.87 4.18 0.29 0.90 4.25 0.25 0.91 4.20 0.28 0.90 4.22 0.45External Awareness 0.77 3.61 0.43 0.85 4.05 0.36 0.87 4.23 0.27 0.91 4.30 0.24 0.88 4.18 0.45Flexibility 0.81 4.31 0.30 0.88 4.36 0.23 0.88 4.29 0.26 0.88 4.33 0.26 0.88 4.33 0.40Resilience 0.81 4.01 0.31 0.88 4.25 0.23 0.90 4.28 0.22 0.91 4.28 0.22 0.91 4.28 0.42Strategic Thinking 0.89 3.56 0.32 0.93 3.92 0.20 0.93 4.10 0.20 0.94 4.15 0.19 0.93 4.06 0.53Vision 0.84 3.82 0.33 0.90 4.03 0.25 0.93 4.10 0.19 0.94 4.15 0.20 0.93 4.09 0.47Conflict Management 0.92 3.93 0.28 0.94 4.13 0.20 0.94 4.07 0.22 0.96 4.05 0.24 0.95 4.11 0.47Leveraging Diversity 0.80 4.45 0.32 0.85 4.52 0.23 0.85 4.48 0.23 0.89 4.41 0.23 0.87 4.47 0.36Developing Others 0.84 4.21 0.29 0.88 4.28 0.21 0.89 4.29 0.21 0.91 4.24 0.28 0.90 4.28 0.42Team Building 0.90 4.05 0.39 0.93 4.26 0.30 0.93 4.22 0.28 0.95 4.16 0.32 0.94 4.22 0.43Accountability 0.87 4.19 0.50 0.91 4.40 0.33 0.93 4.39 0.32 0.93 4.30 0.34 0.93 4.38 0.35Customer Service 0.81 4.06 0.35 0.89 4.25 0.25 0.92 4.27 0.19 0.92 4.26 0.22 0.92 4.26 0.41Decisiveness 0.91 4.11 0.17 0.94 4.27 0.15 0.95 4.27 0.13 0.96 4.28 0.13 0.95 4.28 0.42Entrepreneurship 0.78 3.81 0.43 0.88 4.07 0.30 0.89 4.17 0.28 0.91 4.17 0.28 0.90 4.13 0.49Problem Solving 0.83 4.11 0.30 0.90 4.25 0.22 0.91 4.28 0.19 0.94 4.23 0.19 0.93 4.26 0.44Technical Credibility 0.90 4.02 0.36 0.93 4.34 0.27 0.94 4.37 0.22 0.95 4.25 0.24 0.94 4.32 0.40Financial Management 0.85 3.74 0.40 0.94 4.10 0.19 0.94 4.17 0.16 0.94 4.27 0.17 0.94 4.17 0.49Human Capital Management 0.76 4.04 0.46 0.72 4.22 0.41 0.83 4.27 0.30 0.87 4.21 0.33 0.84 4.24 0.43Technology Management 0.83 3.66 0.38 0.91 4.10 0.22 0.92 4.18 0.18 0.94 4.11 0.20 0.93 4.12 0.50Partnering 0.83 4.00 0.34 0.90 4.27 0.23 0.92 4.31 0.19 0.93 4.29 0.19 0.92 4.30 0.45Political Savvy 0.89 3.69 0.28 0.94 3.99 0.19 0.93 4.18 0.18 0.95 4.26 0.15 0.94 4.14 0.49Influencing/Negotiating 0.88 3.89 0.23 0.93 4.08 0.19 0.93 4.10 0.18 0.94 4.14 0.15 0.94 4.12 0.49

ECQFundamental Competencies 4.23 0.39 4.37 0.29 4.38 0.27 4.33 0.28 4.36 0.37Leading Change 3.89 0.34 4.13 0.26 4.21 0.23 4.23 0.23 4.19 0.45Leading People 4.16 0.32 4.30 0.23 4.27 0.24 4.21 0.27 4.27 0.42Results Driven 4.05 0.35 4.26 0.25 4.29 0.22 4.25 0.23 4.27 0.42Business Acumen 3.81 0.41 4.14 0.27 4.21 0.21 4.19 0.23 4.18 0.48Building Coalitions 3.86 0.28 4.11 0.20 4.20 0.19 4.23 0.17 4.18 0.47

Overall Aggregate 4.03 0.35 4.23 0.26 4.27 0.23 4.24 0.25 4.25 0.43

All RatersSupervisorSelf Peer SubordinateTable 2 - OPM Leadership 360 Descriptive Statistics

39

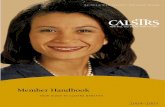

Table 3 – Correlations between 360 Rating Groups on Overall Performance

Variable 1 2 3 Self rating -- Supervisor rating 0.16* -- Peer rating 0.07 0.21* -- Subordinate rating 0.06 0.19* 0.25* Note: '*' is significant p < .05

Table 4 - Intraclass Correlation Coefficients

Group Minimum Maximum Mean Peer 0.00 0.78 0.36 Subordinate 0.00 0.72 0.30

A review of the largely non-significant relationships found in the correlation

matrix suggests little support for the hypothesized relationships. In order to test the

hypotheses controlling for the effect of individual leadership experience, multiple

regression was employed. For all regression equations, the control variable (leadership

experience) was entered, followed by the variable(s) of interest to test the hypothesized

relationships.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 concerned the relationship between perceived supervisor

leadership effectiveness and LSE and MTL, respectively. To test Hypotheses 1, 2a and

2b, LSE, affective-identity MTL and social-normative MTL were regressed on leadership

experience, and perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness in three separate regression

models. Regression results are presented in Table 5. As a set, perceived supervisor

leadership effectiveness and leadership experience did not significantly predict LSE, F(2,

222) = 2.73, ns. Perceived supervisor leadership effectiveness and leadership experience

did significantly predict affective-identity MTL, F(2, 222) = 6.25, p < .05, accounting for

5% of the variance in affective-identity MTL. However, the beta weight for perceived

40

supervisor leadership effectiveness was not significant (

= -.09, ns). Lastly, perceived

supervisor leadership effectiveness and leadership experience did not significantly predict