Rituals, Symbols & Non-Traditional Greek-Letter Organizations

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement ... - CORE

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement ... - CORE

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of LowlandSouth AmericaISSN: 2572-3626 (online)

Volume 3Issue 2 Including Special Section: The Body inAmazonia

Article 4

December 2005

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals ofEnslavement and Markers of Servitude in TropicalAmericaFernando Santos-GraneroSmithsonian Tropical Research Institute, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti

Part of the Anthropology Commons

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tipití: Journal of the Societyfor the Anthropology of Lowland South America by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please [email protected].

Recommended CitationSantos-Granero, Fernando (2005). "Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers of Servitude in TropicalAmerica," Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 4.Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Tipití (2005) 3(2):147–174 © 2005 SALSA 147ISSN 1545-4703 Printed in USA

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers of

Servitude in Tropical America

FERNANDO SANTOS-GRANEROSmithsonian Tropical Research [email protected]

Masters all over the world used special rituals of enslavement uponfirstacquiringslaves:thesymbolismofnaming,ofclothing,ofhairstyle,oflanguage,andofbodymarks…Theobjectiveoftheritualswasthesame:togivesymbolicexpressiontotheslave’ssocialdeathandnewstatus.

—OrlandoPatterson(1982:8–9,53)

In anow famous essay entitled“OfTorture inPrimitiveSocieties,”PierreClastres(1998a[1974])arguedthatAmerindianinitiationritualsalways revolve around the marking and transformation of the initiates’bodies. “It is thebody in its immediacy,”Clastrescontended,“that thesocietyappointsastheonlyspacethatlendstobearingthesignoftime,thetraceofapassage,andtheallotmentofadestiny”(1998a:180).Themarking of the initiates’ bodies, he further argued, always entails somedegreeof torture. Clastres isnot veryprecise aboutwhathemeansby“torture,” but it is clear that what he has in mind is not torture in thesenseofinflictingpain“asameansofhatredorrevenge,orasameansofextortion,”butratheramoremorallyneutralnotionoftorture,understoodmoresimply,followingadefinitionfromtheOxford Universal Dictionary Illustrated (1974:2331) astheinflictionof“severeorexcruciatingpainorsuffering(ofbodyormind).”TheexamplesClastresprovides,involvingthepainfulscarificationandpiercingofthebacks,chests,legs,arms,andgenitals of initiates, can be clearly considered as an instance of tortureinthislattersense.Clastresdoesnotbackuphisargumentwithawiderangeofethnographicexamples.Butweknowfromthepastandpresentethnographic record that these and other forms of torture—such assubjectinginitiatestotattooingwithspines,stingingbyvariouspoisonousantsandwasps,whippingwithlashesornettles,orrubbingwoundswithpoisonous or burning substances—were, and in some cases continue tobe, extremely common in relation to initiation rituals in lowlandSouth

1Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

148 Fernando Santos-Granero

America(seeNimuendajú1939:72;WagleyandGalvão1949:82;Huxley1957:147–148; Murphy and Quain 1966:84; Gregor 1980:228; Seeger1981:167–168; Basso 1988[1973]:68–69; Hugh-Jones 1988:64, 80;Pétesch2000:119;Oakdale2005:149–150). AccordingtoClastres, initiatesaremadetosuffer inordertoprovetheircourageandpersonalworth.Byundergoingtorturewithoutbetrayingpaintheydemonstratetheirreadinesstoachieveanew,moremature,socialstatus. Inaddition, themodificationof theirbodies incollectivepublicceremonies marks them as fellow tribespeople. Through ritual torture,initiatesareremindedthat:“Youareoneofus,andyouwillnotforgetit”(Clastres1998a:184).ClastresarguesthatAmerindianritualtortureisnotonlymeanttoputtheinitiates’valortothetestortomarkthemasmembersofthetribe.Moreimportantly,thecrueltyinvolvedinthemarkingoftheinitiates’bodiesisfundamentallymeanttoindeliblyimprintavitalciviclessononthem.Themainmessageofthislesson,accordingtoClastres,is:“Youareoneofus.Eachoneofyouislikeus;eachoneofyouisliketheothers…Noneofyouislessthanus;noneofyouismorethanus.And you will never be able to forget it”(1998a:186). Clastres’ argument on the social significance of Amerindian ritualtortureisinaccordancewithhisparticularviewoftropicalforestsocietiesas“societiesagainstthestate,”thatis,asrelativelyegalitariansocietiesstrivingtokeepincheckthesocialforcesleadingtocentralizedandhierarchicalforms of power and authority. What distinguishes most Amerindiansocieties is “their sense of democracy and taste for equality” (Clastres1998b:28). InClastres’ view,with a few—mostlyArawak—exceptions,Amerindiansocietiesarecharacterizedbyalackofinternalstratificationand strong forms of authority. In this paper I contend that Clastres’perspectiveisrightinemphasizingthatinAmerindiansocietiesthebodyisthemostimportantmeansfortheinscriptionofsocialknowledge.Heisalsorightinassertingthatsuchinscriptionofthebodyoftentakesplaceundertheformoftortureduringritualsofpassage.Idisagree,however,withhisinterpretationthatthemessageimpartedthroughritualtortureis one whose main objective is to stress tribal membership and socialequality. I argue instead that the kind of Amerindian societies Clastres hadin mind when he elaborated his society-against-the-state theory weresocietiesextremelymodifiedbycenturiesofforeigndiseases,encroachment,displacement,genocidalpolicies,enslavement,andmarginalization.Theywere often the stubborn remnants of their former selves. Even thoseisolatedpeopleswhowerethoughttohaveescapedthehorrorsofcontactswith European agents were subsequently discovered to be regressivesurvivors of such processes, experienced in a more or less remote past.

2

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 149

By the time Clastres elaborated his theory, powerful paramount chiefs,regionalconfederations,largepoliticalcenters,elaboratetempleceremonies,extensive public earthworks, and native forms of servitude1—includingslavery—had ceased to exist (see Heckenberger 2003). Consequently,these features—attested to by abundant archaeological and historicalevidence—wereignored,orsimplydisregardedasbeingtheexaggerationsof overly enthusiast European adventurers eager to impress their royalpatrons.OnlymuchlaterwouldanthropologistslikeClaudeLévi-Straussacknowledgethat:“Therewherewebelievedourselvestohavefoundthelastevidenceofarchaiclifewaysandmodesofthought,wenowrecognizethe survivorsof complexandpowerful societies, engaged inahistoricalprocessformillennia,andwhichhavebecomedisintegratedinthelapseof two or three centuries, a tragic accident, itself historical, which thediscoveryoftheNewWorldwasforthem”(1993:9,mytranslation). In this article Iwill analyze the roleof ritual torture in threenon-Arawak Amerindian slaving societies, which, at the time of contact,2practicedlarge-scaleraidingandcapturingofenemypeoplesandpresentedimportantsignsofsocialstratificationandsupralocalformsofauthority.I argue that in these societies war captives—mostly young women andchildren,sinceadultmenandolderwomenweregenerallykilledinwarfareengagements—were not integrated immediately as wives or adoptivechildren,butwererathermarkedandretainedasslaves.Thiswasachievedthroughritualsofenslavementinwhichthebodiesofwarcaptivesweremarked actually or symbolically, by imposition or default. Such ritualswere theoppositeof tribal initiation rites. Rather than stressing socialmembershipandequality,theyweremeanttosetcaptivesapartasalien,less-than-humanandinferiorsubordinates.Thus,Icontend,Amerindianritualtortureshouldnotberegardedonlyasaninclusionarymechanismattheserviceofsocialintegrationandegalitarianism,butalsoasanexclusionarymeansattheserviceofsocialmarginalizationandstratification.

RITUALS OF ENSLAVEMENT

The widespread notion—based mostly on twentieth-centuryethnographic information—that most Amerindian raiding is aimed attakingwomenaswivesandchildrentobeadoptedhashadtheunfortunateconsequenceofconcealingtheviolenceinherenttonativeraiding.Moreimportantly, ithasconcealedtheproductionofcaptiveslavesasasocialprocess.Inmanycontact-timetropicalforestsocieties,warcaptiveswerenotmeanttobeincorporatedimmediatelyintotheircaptors’householdsasconcubinesoradoptedchildren.Onthecontrary,theyweremarkedas

3

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

150 Fernando Santos-Granero

beingalien,inferior,andsubordinate,hence,noteligibleforfullmembershipinthesocietyoftheircaptors.SuchmarkingwasachievedthroughwhatPatterson has called “rituals of enslavement” (1982:52). It should benoted,however,thatAmerindianslaverywasnotafixed,permanentstatus.Throughthepassageoftimeandafterundergoingwhatfromthecaptors’pointofviewwasconsideredtobea“civilizing”process,warcaptives—butmoreoftentheirchildrenorgrandchildren—wereincorporatedfullyintothecapturingsociety. The main feature of captive slavery in native tropical America, aselsewhere,isnotonlythatthelivesofwarcaptivesarealienatedbytheircaptors, but that they are “socially dead,” a condition of uprootedness,loss of identity, and disenfranchisement violently imposed upon themthroughwar,capture,andritualdebasement(Patterson1982).Incontact-time tropical America, the transformation of captives into slaves wassymbolicallyaccomplished throughelaborate ritualsofenslavementanddesocialization. Aimed at depersonifying captives—depriving them oftheirpreviousidentitiesandsocialpersonas—andrepersonifyingthemasgenericdependents(Meillassoux1975:21),theseritualsinvolvedvarioussymbolic acts including the rejection by captives of their past lives andkinship ties, the impositionofnewnames, themarkingof theirbodies,andtheassumptionofanewstatuswithinthecapturingsociety(Patterson1982:52).Ritualtorturewasascentralintheseritualsofcaptivityasitwasininitiationrites. Despite theirnewstatus,warcaptives foundthemselves ina limbiccondition, no longer belonging to their societies of origin nor fullyassimilated into the society of their captors (Vaughan 1977:100). Thefear of death that led them to captivity (Taussig 1999), and the factthat theyowedtheir lives to theirmasters (Condominas1998),markedcaptiveslavesindeliblyasbothinferiorandmarginalintheeyesoftheircaptors.IntropicalAmerica,thisstigma—whichgenerallypersistedlongafter captives had lost their slave status and had been assimilated intothecapturingsociety—wasexpressedinavarietyoflinguisticandbodilymarkers. Thetermsusedbymembersofslavingsocietiestorefertocaptiveslavesweremultivocalandcouldbeusedalternativelytodesignate“strangers,”“enemies,”and“captives.”Thissuggeststhat,atleastinsomeAmerindianworldviews,allstrangerswereconsideredtobepotentialenemies,andallenemiespotentialslaves.NotingthatasimilarlogicoperatedinancientRome,wheretheterm“hostis”meantboth“stranger,”“enemy,”or“virtualslave,”Lévy-Bruhlarguedthatslaveryshouldnotberegardedsimplyasajuridicalrelationship,butthatitcontainedanethnicdimensionthatmade

4

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 151

theservilerelationshipindelible(1931:7,10). This also holds true for native tropical America, where exoslaverywasthepredominantformofextremedependency.3Membersofslavingsocietiesconsideredtheirenemiesclosertotheanimalsphereandthusaslesshumanthanthemselves.Theallegedlackofhumanityoftheirenemiesisexpressed inaseriesof reference terms,metaphorsandmyths,whichcaptors used to justify raiding and enslaving them. In some instances,theseAmerindianrepresentationsarecoupledwithahierarchicalgenderedimagery in which masters are seen as occupying a masculine position,whereassubordinatesoccupyafeminineone.Inotherinstances,theygohand inhandwithmetaphors that equatewar captives to theyoungofkilledgameadoptedas“pets”by thekillersof theirparents (seeFausto1999). ThefollowingexamplestakenfromwidelydistantgeographicalandculturalareasprovideabundantevidenceofthelinguisticandbodilymarkersusedtodenotethesubordinatestatusofwarcaptivesinAmerindianslavingsocieties.4Theyshowthat,fromanAmerindianperspective,captiveslaveswerealienpeoplesintheprocessofbeingcivilized.

THE KALINAGO OF THE LESSER ANTILLES

Kalinagopeople,inhabitingtheLesserAntillesandspeakingahybridlanguage with an Arawakan substratum modified by important Caribinfluences,werecontacted in1493,duringColumbus’ secondvoyage toAmerica. Kalinago villages were composed of a group of interrelatedfamiliesundertheleadershipofagrandfatherorgreat-grandfather,whoactedbothasvillageandwarleader(Breton1978[1647]:134).5Insomeislands,villageleadersrecognizedoneortwoamongthemasparamountchiefswithauthorityoverseveralvillagesorovertheentireisland(delasCasas1986[1560]:I,454;Rochefort1666[1658]:313–4). At the timeofcontact, themainsocialdivision inKalinagosocietywasthatbetweenKalinagopeopleandcaptivestakeninwarorobtainedthroughtrade.Duringthetradewindseason,Kalinagowarriorsembarkedon long-distance maritime expeditions against the Arawak-speakingpeoplesoftheGreaterAntillesandtheGuianacoast.Thesewerelarge-scale expeditions that could muster several dozens of war canoes, eachcarrying twenty-five to thirty warriors (Anonymous 1988 [1620]:185).Mostenemywarriorsandoldpeoplewerekilledinbattleorexecutedafterbeingdefeated.Onlyafewadultmen,andasmanychildrenandyoungwomenaspossible,weresparedandtakenbacktothevictors’settlement.

5

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

152 Fernando Santos-Granero

The fate and status of these captives varied according to gender,ethnicorigin,andage.AdultmaleAmerindiancaptivesweretormented,executed,andeatenincannibalisticcelebrationsshortlyaftertheircapture.Incontrast,AfricanandEuropeanmalecaptiveswereexcludedfromthissymbolic system of exchange with the enemy and put immediately towork. Amerindian boys were raised as household servants, and wouldbe executed and consumed in cannibalistic rituals when they becameadults(Coma1903[1494]:250–1;Anonymous1988[1620]:187).Youngcaptivewomenwereeithertakenasconcubinesbytheircaptors,orgivenasmaidservantstotheirwives(Coma1903[1494]:251). Kalinago had a rich vocabulary to refer to enemies taken in warand kept as servitors or concubines. This vocabulary was all the moreelaborate,sinceKalinagolanguagecomprisedfemaleandmaleregisters.HereIonlypresentthemaleterminology.TheKalinagotermforenemyis etoutou, or itoto (Rochefort 1666 [1658]: Appendix). Among therelatedCarib-speakingKali’naofGuiana, this term isnotonlyused todesignateforeignersandenemies,butalsoprospectivepoitoorsons-in-law(Whitehead1988:225).Thissemanticequivalencehasbeentakenasanindicationthatwarcaptiveswerenotmeanttobecomeslaves,butrathertobeincorporatedthroughmarriageassubordinatesons-in-law.ThiswasnotthecaseofKalinagopeople,amongwhommalecaptiveswereneverallowedtomarryKalinagowomen. Kalinagopeopleequatedwarcaptivestoanimalprey.Rochefort(1666[1658]:Appendix)assertsthatoneofthetermsbywhichKalinagomasterscalledtheircaptiveswasnïouitouli,whichhetranslatesas“myprisonerofwar.”ButinhisdictionaryBretonrenderstherootofthisterm,ioüítouli,as“thecapturethatImade,”inthesenseof“thepreythatIhavehunted”(1665:390). Thus, the termnïouitouli couldbebetter translatedas“mypreythatIhavecapturedinwar.”Thedifferentialfateofcaptiveslaveswasalsomarkedlinguistically.Adultmalecaptivesdestinedforexecutionwerecalledlibínali,whereasfemaleandinfantcaptivesmeanttobekeptaliveasservitorswereknowngenericallyastámon(Breton1665:45;1666:152).6

Theritualmarkingofwarcaptivesasslavesbeganshortlyaftertheircapture. After arriving to their captors’ village, all war prisoners weresubjectedtothefury,insultsandbeatingsofthelocalpeople,whichweretobedreaded(Labat1724[1705]:I(2),11).Almostimmediately,Kalinagomastersproceededtoshearthehairofthefemaleandinfantcaptivestheyhadtaken(Anonymous1988[1620]:187–8;DuTertre1654:421).Neveragainweretheyallowedtogrowtheirhairlong,asbothKalinagomenandwomennormallyworeit. Thus, longhairwasconceivedofasasignof“independenceandliberty,”whereasshorthairwasregardedasamarkof

6

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 153

servitude(Breton1978[1647]:60–61). Kalinagopeoplecuttheirhairononlytwooccasions:ataroundtheageoftwo,whenchildrenwereweanedandallowedtoeatfishorwheneveraspouseorcloserelativedied(Rochefort1666[1658]:340;Anonymous1988[1620]:191).Inthefirstcase,theritualcuttingofhairmarkedtheend of infancy. In the second case, it marked the end of an affinal orkinshiptie.Inlightofthesepractices,theshearingoffemaleandinfantcaptivesmustbeseenasmarkingtheendofthecaptives’pastlivesandtheobliterationoftheirprevioussocialties. Fromthenonwards, all captiveswerenotaddressedby theirnamesbutsimplyastámon,malecaptiveslave,oroubéherou,femalecaptiveslave(Anonymous 1988 [1620]:187–188). French sources assert that youngmalecaptiveswerealsosometimesaddressedasmon boucan(“mysmokedmeat”)inreferencetothefatethatawaitedthemwhentheybecameadults(Chevillard1659:118).Thiscontributedtotheprocessofdepersonificationofwarcaptivesandtheirrepersonificationassubordinates.Byrefusingtouse their names, Kalinago masters deprived their captives of their pastidentityandevenoftheirhumanity,sincethenamingofaKalinagoboyorgirlonemonthaftertheirbirthmarkedthebeginningoftheirexistenceashumanandsocialbeings(Anonymous1988[1620]:167). Atthesametime,byaddressingthemas“my(maleorfemale)captiveslave,”Kalinagomastersprovidedtheircaptiveswithanew,genericidentityasservitors.Onlymuchlater,aftertheyhadadoptedKalinagolanguageandcustoms,didcaptivesgothroughasecondprocessofrepersonification,andweregivenapersonalname(Chevillard1659:117).However,sincethesenamesdifferedfromthosetheyhadwhentheywerecaptured,theirnew identity must be seen as simply one more step in the process ofremovingcaptivesfromtheirsocietiesoforiginandmovingthemintothesocietyoftheircaptors. In addition to being deprivedof their names and having their haircropped,incontacttimescaptiveboyswerealsoemasculated.Reportingon Columbus’ second voyage to America, Diego Alvara Chanca (1978[1494]:31) writes that when Kalinago “take any boy prisoners, theydismemberthem.”Heclaimedtohaveseen“threeoftheseboys…thusmutilated.”Thiswasconfirmedbyotherauthorswhoparticipatedinthistrip, suchasGuglielmoComa(1903:250)andMigueldeCúneo (1928[1495]:280),whoaffirmsthatinGuadeloupehesawtwoadolescentboys,eacharoundfifteenyearsofage,“whohadtheirgenitalmemberscutclosetotheirbellies.”Suchwitnessinformationisconfirmedbylater,generallyreliable sources (suchas, forexample,de lasCasas1986 [1560]:I,370).Thesesourcesarenotclearaboutwhethercaptiveboyswerealsocastrated

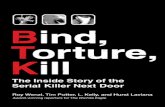

7

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

154 Fernando Santos-Granero

(meaninghavingtheirtesticlesremoved,apartfromhavingtheirpenisescutoffclosetothebelly).ButFerdinandColumbus’versionofhisfather’sencounterwithKalinagopeoplesuggeststhatsuchcastrationsmighthavebeenthecase.“Thesemen”hesays,“hadhadtheirvirilememberscutoff,fortheCaribscapturethemontheotherislandsandcastratethem,aswedotofattencapons,toimprovetheirtaste”(1992[1593]:117). Itisdifficulttoassesstheveracityofthisinformation,butitistellingthattheseallegationswerenotdirectedatanyother indigenouspeopleswithintheCaribbeanregion.Ingeneral,SpanishagentsseldomaccusedAmerindiansof suchpractices. Incontrast, accusationsof cannibalism,sodomy,andincestweremadequitefrequently.ThefactthatatthetimeoftheConquestofAmerica,penisexcision—involvingeithertheremovalofthetestesortheexcisionofbothtestesandpenis—wasstillcommonundercertaincircumstancesintheOldWorld,suggeststhatthispracticewasnotnecessarilyviewedwiththesamehorrorthenaswedonowadays.Thus,itseemslikelythatimputingthispracticetoKalinagopeoplewaslikelynotaSpanishfabricationmeanttomakethemseemtobe“savages.” IfemasculationwasindeedanimportantpracticeinKalinagoritualsof enslavement, by the seventeenth century it hadbeen abandoned, forit isnot reported inanyother source. There is,however,evidence thatKalinagocontinuedtocutoffthepenisesofkilledenemies,whichwerethenthrownintothesea(Anonymous1988[1620]:189).ThereisampleevidencethatKalinagocontinuedtoexecuteandconsumecaptiveboysincannibalisticritualsoncetheyreachedmanhood. Femalecaptiveswerenotonlyforbiddentogrowtheirhair,butwerenot allowed to wear the echépoulátou, the leg bands used by Kalinagowomen(Breton1978[1647]:62).ThispracticewasreportedveryearlyonbyChanca,whoclaimedthatitwasthelackoflegbandswhichallowedtheSpanishtodistinguishKalinagowomenfromfemalecaptives(1978[1494]:29). Echépoulátou were ligatures made with cotton thread rightaboveandbelowthecalves,sothatthelatterlookedpuffed(seeFigure1).Kalinagogirlsweregiven theirfirst legbandsafterundergoingpubertyinitiation rituals (Labat 1724 [1705]:5). These cotton ligatures wereprotected with natural oils from getting wet, and were never taken offunlesstheyrotted,orasaconsequenceofsomegraveaccident.Kalinagowomen“valuetheselegbandsasthemostbeautifuloftheirornamentsandthemostinfalliblesignoftheirfreedom,andbecauseofthistheydonotstandanyslavetowearthem”(Breton1665:197). Deprivedof theirnames,addressedonlyas captive slaves, andwiththeirbodiesmarkedbymutilationsortheabsenceofornamentsthatwerethesoleprerogativeoftheirmasters,warcaptivesinKalinagosocietywere

8

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 155

forced—atleastduringtheyearsimmediatelyaftertheircapture—toleadalimbiclifeofalienationandmarginality.

[Source: Taylor 1888:110; based on a 1667 engraving by Sebastien Le Clerc.]

THE CONIBO OF EASTERN PERU

Conibopeople,thelargestandmostpowerfulofthePanoan-speakingsocieties of eastern Peru, occupied both margins of the Ucayali River,

Figure 1. Kalinago high-ranking woman, 1600s.

9

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

156 Fernando Santos-Granero

fromthemouthoftheTamayainthenorthtothatoftheMashanshainthesouth,aswellasthelowerportionofthePachiteaRiver.Theywerefirstcontacted in1557,when theSpanishconquistador JuanSalinasdeLoyola navigated upriver along the Ucayali and Urubamba rivers (Alès1981).WhiletraversingConiboterritory,Salinasfoundnumerousvillagescomposedof200to400houses(Alès1981:88).Eachvillagehaditsownleader, who, according to the chronicler, “were obeyed and respectedmuchmore than thosedownriver [along theMarañonRiver]” (inAlès1981:90). ConibopeopleformedpartofaheterogeneousregionalpowersysteminwhichtheynotonlycompetedforsupremacywiththeequallypowerfulCocama and Piro, but constantly raided their weaker semiriverine andinterfluvial neighbors. Among these, their favorite targets were fellowPanoan peoples such as the Uni (Cashibo), Amahuaca, Remo, Sensi,Capanahua,Mochobo,andComabo,andtheirArawak-speakingneighbors,theAsháninka,Ashéninka,Machiguenga,andNomatsiguenga.Coniboregarded all their neighbors as nahua, a term meaning both“foreigner”and“enemy”(Anonymous1927:413).Theactionoftakingcaptiveswasdescribedby the termyadtánqui (tomakecaptives),whereyadtámeans“captive,” and áqui means “to make” (Marqués 1800:143, 160). Sinceyadtánquialsomeans“tograb”or“seize”(Marqués1800:145),theliteralmeaningoftherootyadtá(captive)mustbe“theseizedone.” Conibo people had a second term to refer to war captives, to wit,hina, which had the double meaning of “household servants” and“domesticatedwildanimals”(Marqués1800:143;Anonymous1927:405).Theimplicationsofthesimilebetweencaptiveslavesandpetshavebeenexplored by several authors (Viveiros de Castro 1992; Menget 1996;Fausto1999,2001).HereIstresstheideathatConibopeopleregardedmostoftheirneighborsasbeinglesshumanthanthemselvesor,atleast,asrepresentingadifferentformofhumanity,oneclosertoanimality(DeBoer1986:238). Thiswasespeciallytrueofthosepeopleswhodidnotweartunicsandwho did not practice head elongation or female circumcision—culturalpracticesthatConibopeopleregardedastheutmostsignsofcivilization.From a Conibo point of view, their most savage neighbors were thePanoan-speaking Uni (Cashibo), Amahuaca, Remo, Sensi, Mayoruna,and Capanahua, who went around naked, had round heads, and onlyinthecaseoftheUnipracticedfemalecircumcision. Thesebackwoodspeoples were considered to be cannibalistic, dirty, and savage. Slightlyless savagewere theArawak-speakingAshaninka,whowore tunics butdidnotpracticeheadelongationandfemalecircumcision,andPiro,whoworetunicsandpracticedfemalecircumcision,butdidnotelongatetheir

10

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 157

heads.ThePano-speakingShipiboandSetebo,peopleswhohadallthesepractices,wereconsideredenemiesbutnotsavages.AttheotherextremeofthiscontinuumweretheConibo,whoviewedthemselvesastheepitomeofcivilization. Most Conibo raids were directed at peoples with round heads, asituationreminiscentofthePacificNorthwestCoast,wherethesouthernWakashan-speaking peoples who practiced head elongation only tookcaptives from the northern British Columbia coastal peoples who didnot, and vice versa (McLeod 1928:645–6477; Ruby and Brown 1993;Leland1997;Hajda2005).ThepreferredvictimsoftheConibowerethe“savage”peoplesof the interfluvial regions. Conibowerevery awareofthedifficultiesinherentintheprocessofhináqui,theraisingormakingofcaptiveslavesandpets(Marqués1800:148;Anonymous1927:405).Adultmaleswerekilledimmediately,forConibowarriorsknewthattheywouldattempttoescapenomatterhowfarawaytheyweretaken,orthattheywouldotherwiselanguishanddiesoonthereafter(Ordinaire1887:288).Toavoidrevengeoranyfutureproprietaryclaims,Conibowarriorsalsokilledallcloserelativesoftheyoungwomenandchildrentheyabducted(Ordinaire1887:288).Tolessenthefeelingofregretthatcaptivesmightexperienceafterbeingremovedfromtheirvillages,Coniboraiderstorchedtheirhomes. Withno familyorplace togobackto, femaleand infantcaptiveswereexpectedtosubmitmorereadily. As soon as Conibo raiders returned home, they dressed whatevercaptivestheyhadbroughtwiththemintheConibomanner:wraparoundskirts for the women, cotton tunics for the men (Roe 1982:84). Sincemost interfluvial peoples wore only string belts that left their genitalsexposed—somethingthatConibopeopleabhorredasasignofimmodestyandsavagery—thedressingofwarcaptivesmustbeconsidereda“civilizing”act,aswellasafirststepintheirprocessofsocialintegration. Together with this, they cut the hair bangs of female captives twofingers above their eyebrows with the double purpose of distinguishingthemfromtrueConibowomen,whosebangsreachedtheireyebrows,anddenotingtheirstatusas“halfcivilized”people(Roe1982:84).Inaddition,theycutthehairofyoungmalecaptivestodifferentiatethemfromConibowarriors,whoworetheirslong.Malecaptiveswerealsodeprivedoffacialhairiftheyhadanyonthegroundsthattheyotherwiselooked“uglyandmonkey-like,”andresembledthehairyforestogresofConibomythology(Roe1982:84). Insomecases,theyoungest,prepubescentfemalecaptiveswerealsocircumcised(DeBoer1986:238).FemalecircumcisionofConibonubilegirlswascarriedoutinlargecelebrationsknownasani shreati(“thegreatlibation”)afterhavingundergoneayear-longperiodofseclusion(Morin

11

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

158 Fernando Santos-Granero

Figure 2: Conibo warrior with captive woman, mid-1800s. [Source: Marcoy 1869:I, 648.]

12

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 159

1998:392). Circumcision consisted in the removal of the clitoris andlabia majora,andtheperforationofthehymen(Stahl1928[1895]:161–163).Conibopeoplearguedthatclitorisexcisionimpededwomenfromdeveloping“uncivildesires”andthusmadethemmore“civilized.”FemalecircumcisionwasthusconsideredtobeasignoftrueConibowomanhood.For this reason, captive women who were past their puberty and couldnotbecircumcisedwereregardedasbeinginferiorandnotappropriateasprospectivewives. Conibo ritualsof enslavementhad thepurposeofmarkingcaptivesbothasoutsidersand insiders,asugly foreignersbutalsoasprospectiveconcubines or adoptive children. But most captives had physicalcharacteristics (round heads), or cultural marks (facial tattoos, like theRemo, Capanahua and Mayoruna), that marked them indelibly asforeignersandcaptivesnomatterhowConiboizedtheybecame.Thelackofelongatedheadswasespeciallysignificant. Head elongation was achieved by compressing the forehead andocciputofbabiesbetweenasoftpadandapaddedboardduringthefirstmonthsoftheirlives.AccordingtoStahl,thispracticewasconsideredasimportantafeatureasfemalecircumcisioninthedefinitionoflegitimateConibomenandwomen,sinceitwasbelievedthattheflatteningoftheheadrepressedcapriciousnessandrebelliousnessandthusinducedacivildisposition(1928[1895]:164).Inthiscontext,havingaroundheadwasasignbothofcaptivestatusandofirremediableincivility(Morin1998:390–391). Thus, the contrast between Conibo people, with their elongatedheads,beautiful tunics andprofusedecoration, and their round-headed,“naked,”andunadornedcaptivescouldnothavebeengreater, as iswelldepictedinanineteenth-centuryengravingbyMarcoy(seeFigure2).

THE GUAICURÚ OF THE GRAND CHACO

The first Europeans to enter in contact with the Guaicurú of theParaguayanGrandChaco, in1548,depicted themashaving some typeofdominanceoverneighboringpopulationssuchastheSchenne(Chané,better known as Guaná) andTohannos (Toyana), who were said to bethesubjectsoftheGuaicurú“inthesamewayasGermanrusticsarewithrespecttotheirlords”(Schmidel1749:22).Insubsequentcenturies,andespeciallyafter theyadoptedthehorse in the late1500sorearly1600s,Guaicurúslaveraidinganddominanceovertributarypopulationsbecamelegendary. Atthetimeofcontact,Guaicurúwerelocatedonthewesternmarginsof the Paraguay River, close to where the Spanish founded the city of

13

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

160 Fernando Santos-Granero

Asunción(NúñezCabezadeVaca1585[1544]:76v;Techo1897[1673]:II,159).Theyweredividedintoseveralnamedcacicatos,orchieftainships(Lozano1733:62;SánchezLabrador1910–1917 [1770]:I, 255). Thesechieftainshipswereinturndividedintoparcialidades,orregionalgroups,headedbyaprincipalchief,andintonumerouscapitaníasortolderías,localgroupsorcampsledbylower-rank“captains.”Themostimportantamongthelocalgroupchiefswasrecognizedasparamountchiefoftheregionalgroup.Themostimportantoftheregionalgroupchiefswasrecognizedasparamountofthechieftainship.Therewerenochiefs,however,withauthorityovertheentireGuaicurú“nation.”Significantly,thenumberofchieftainshipsvariedthroughtime. Since the first contacts, European sources pointed out the highdegree of stratificationofGuaicurú society (Schmidel 1749 [1548]:21).Accordingtothesereports,Guaicurúweredividedintopeopleofchieflystatus,warriors, andordinary freemenor commoners (Lowie1948:348;Steward and Faron 1959:422). The status of captive slaves, nibotag’ipi(Unger1972:89),wasevenlowerthanthatofcommoners,andthatofthetributaryArawak-speakingGuaná—highlystratifiedthemselves—variedaccordingtotheirpositionintheirownsociety. Guaicurúpeopleregardedthemselvesassuperiortoalltheirneighbors,including the Spanish and Portuguese, whom, they claimed, they had“pacified”despitetheirmuchproclaimedbravery(SánchezLabrador1910–17[1760]:II,52–3;Serra1845[1803]:204–5).Forthisreason,accordingtoPortuguesechroniclers,Guaicurúpeopleconsideredallothernationsas their cativeiros, or captives, who “owed them tribute and vassalage”(Florence1941[1829]:62–3). The term that Portuguese authors translate as cativeiros seems tobenibotagi. Thistermdesignatedpeopleinabroadrangeofsituations.It comprised individuals taken as captives in raids and intertribal wars,familiesorindividualsfromtributarypopulationswhoattachedthemselvesas servants in Guaicurú households, people from tributary populationswhoweresentbytheirlocalchiefstoperformserviledutiestemporarilyforGuaicurúhigh-rankingfamiliesaspartoftheirtributaryobligations,andpeoplewhohadsoughtanalliancewiththeGuaicurúeithertoputanendtoconstantraidingortoavertthethreatofwar. Victoryritualsincludedtheparadingofhandcuffedcaptivesandthedisplayofheadtrophiesorscalps.Localwomendancedandsangaroundthevillageholdingtheseremains,allthewhilepraisingthevaloroftheirfathers,brothersandhusbands( Jolís1972[1789]:314).Therecanbenodoubtthatoneoftheaimsoftheseceremonieswastomarkcaptivesasdespisedforeigners,butthesourcesaresilentabouthowwarcaptiveswere

14

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 161

dealtwithduringthefirststageoftheirincorporationintothesocietyoftheircaptors.Weknow,however,thattherewereseveralwaysinwhichwarcaptivesweremarkedassuchtodistinguishthemfromtheirGuaicurúmasters. OneoftheculturalpracticesforwhichGuaicurúpeoplewererenownedwasthatofpluckingalltheirbodyandfacialhair,includingeyebrowsandeyelashes(Prado1839[1795]:28).Theydidthissoas“nottolooklikethegreaterrhea(Rhea americana),towhom,theysay,theSpanishresemble”(Lozano1733:64).Inotherwords,theydidsonottolooklikeanimals.Thisconcernwasextendedtotheuseofthefeathersofthegreaterrheaitself.Guaicurúmenworeavarietyoffeatherornaments—headdresses,armbandsandlegbands—madeofallkindofcoloredfeathers(Prado1839[1795]:29;Lozano1733:65).Theyrefused,however,touseheaddressesmade of greater rhea feathers. These were reserved for the making ofshamanic feather fansandwomen’sparasols,andweretheonly feathersthat male captives were allowed to use (Sánchez Labrador 1910–1917[1760]:I,214). GiventhatgreaterrheasseemtosymbolizetheepitomeofanimalityintheGuaicurúworldview,theirusebycaptivesmustberegardedasmarkingtheirclosenesstothesphereofanimalsand,thus,theirless-than-humanhumanity.Guaicurúmenpaintedtheirbodieswithredbixa (Bixa orellana),blackgenipapo (Genipa americana)andthewhiteflourof thenamogoligipalm (Acrocomia totai)when theywent towar. However,male captiveswere only allowed to paint their bodies with black charcoal (SánchezLabrador1910–1917[1760]:II,I,286).Thusblackened,andwithcrownsof greater rhea feathers, male captives looked like the antithesis of thecarefullypaintedandprofuselyornamentedGuaicurúwarriors. Femalecaptivesdifferedfromtheirmistressesbytheirfacialdesignsandbythemethodstheyusedtoapplythem.Guaicurúwomenpaintedelaboratedesignsontheirfacesandbodies.Thehighertheirrank,themoreelaboratethedesigns.Sometimestheyeventattooedtheirarmsfromtheirshoulders to theirwrists,whichamongGuaicurúpeoplewasamarkofextremenobility(SánchezLabrador1910–1917[1760]:I,285).However,nohigh-rankingGuaicurúwomanwould,underanycircumstance,tattootheirfaces.Facialtattooswereconsideredtobe“themarkoftheirinferiorsandservants,”meaningcaptiveslavesandGuanáhouseholdservants,butalsoGuaicurúcommoners(SánchezLabrador1910–1917[1760]:I,285). Sánchez Labrador reports that female captives and low-rankingwomenweretattooed“fromthehairlinetoabovetheireyebrowswiththickblacklinesresemblingthekeysofanorgan”usingafishboneandtheashesof the leavesofacertainpalm(1910–1917[1760]:I,285). Inaddition,

15

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

162 Fernando Santos-Granero

they sometimes tattooed their chins. This pattern—indicating servilestatus—was still inusefifty years later,whenHerculesFlorence visitedtheGuaicurúaround1825anddrewtheportraitofaChamacococaptivewomanboughtbytheCommanderoftheBrazilianFortofAlbuquerquefromherGuaicurúmasters(seeFigure3).

Figure 3: Chamacoco slave woman, early 1800s. [Source: Florence 1941:52.]

Apart from these differences in personal ornamentation, Guaicurúmarkedtheircaptiveslaveswiththeirownpersonalmarks(Boggiani1945[1895]:228).Itissaidthatthesemarkswereappliedtoalltheirpersonalbelongings for example, animals (horses and dogs) or objects (combs,smokingpipes,weavingutensils,gourds,andboxes).Sometimes,Guaicurú

16

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 163

chiefsdisplayedtheirpersonalmarksinflagsplantedinfrontoftheirtents.ItisreportedbyBoggianithatpersonalmarkswerealsoappliedtopeople,especiallywomen. Confused about this practice, some authors affirmed thatGuaicurúwomenboreontheirbodiesthesamemarksoftheirhorses(Prado1839[1795]:30). Other observers asserted that most Guaicurú women borethesemarksontheirchests,butclaimedinsteadthattheywerethemarksofthemaleheadsoffamilies,who“appliedthemtoallwhichtheypossessed”(Castelnau1850–1859[1845]:II,394).Boggiani,wholivedmanyyearsamong Guaicurú people, claimed, however, that both Guaicurú chiefsandtheirwiveshadtheirownpersonalmarks (1945[1895]:228). Thisindicatesthatpersonalmarkswerenotamaleprerogative.Italsosuggeststhat Castelnau’s interpretation is wrong and that only certain women,namelycaptivewomen,weremarkedbytheirmastersinsuchaway. Atfirstsight,itwouldseemthatthiscustomderivedfromtheSpanishand Portuguese practice of branding their horses. This practice wouldhavebeen adoptedbyGuaicurúpeople in the late1500s togetherwiththehorse.Thereis,however,strongevidencethatthepracticeofmarkingpeopleexistedinAmericapriortocontact.ThomasHariot(asdepictedinLorant1965:271),theEnglishastronomerwhoin1588wroteaworkon thenativepeoplesofVirginia, reported that:“All inhabitantsof thiscountryhavemarksontheirbackstoshowwhosesubjectstheyareandwheretheycomefrom.”AmongnativeVirginianschieflymarkssignifiedpersonal allegiance and local affiliation rather than personal possession.Butinotherareas,suchaslowlandCostaRica,itwasreportedearlyonthatoneofthemostvaluabletradeitemswasacertainblackpowderobtainedfromburningpinewoodthatwasused“tobrand[i.e.,tattoo]Indiansasslaveswithasmuchinventivenessastheirmastersseemfit”(Oviedo1851[1535]:204).ThissuggeststhatGuaicurúmarkingofwarcaptives—andespeciallyof femalecaptives—wasapre-colonialpractice. If this is thecase,weshouldconcludethattheelaboratemarksthatGuaicurúbrandedontheirhorsesincolonialtimeswereinspiredbythetattooingofcaptiveslavesandotherpersonalpossessionsratherthantheotherwayaround.

MARKERS OF SERVITUDE

As it is clear from the above examples, the depersonification andrepersonificationofwarcaptivesoftenentailedtheimpositionofspecialmarkings on their bodies. This is consonant with the Amerindianpropensity to use bodies as the main instruments to convey social andcosmologicalmeanings(Seegeretal.1979;Turner1995),aswellas the

17

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

164 Fernando Santos-Granero

privilegedmeansforimprintingandpreservingthememoryofchangesofstatus(Clastres1998a).Ithasbeenarguedthatinthesesocietiesbodilymodificationsdonot“symbolize”changesinsocialidentity,butratherthatcorporealtransformationsandtransformationsofsocialpositionareoneandthesameprocess(ViveirosdeCastro1979:40–41).Forthisreason,the inscription and transformation of bodies is a central aspect of allAmerindianinitiationrituals.Butpreciselybecausebodiesconstitutethemaininstrumenttodenotechangesinsocialposition,Amerindiansalsoprivilegethemtomarkthepassagefrompersonalautonomytoservility.Having been violently deprived of their previous social personas andidentities,captiveswereprovidedwithanew,servileidentitythroughtheinscriptionontheirbodiesofsymbolicoractualmarkersofservitudeandslavery. TheimprintingofservilestatusthroughwhatMauss(1936)called“les techniques du corps,”wasachievedthroughseveralmeans:byemphasizingthosebodilymarksthatbetrayedtheforeign,less-than-humanconditionofwarcaptives;byunderscoringthelackofbodilymarkscharacteristicoftheircaptorsandconsideredtobesignsoffullhumanity;byprohibitingtheuseofitemsofclothingorornamentsthatweretheprerogativeoffullmembersofthecapturingsocietyandbyimposingdebasingornaments,body marks, and bodily mutilations. Although not all of these bodytechniquescanbedescribedasformsoftorture,allritualsofenslavementinvolvedsomedegreeofritualtorture. Some authors have dismissed these markers of servitude as aninconsequentialattempttointroducedistinguishingtraitsbetweencaptorsandcaptives(Whitehead1988:182).ThisviewseemstobeinfluencedbythehighlyegalitarianethosofAmerindiansocietiestodayaswellasbythecharacteristicsofpresent-dayAmerindianformsofintertribalraiding.Aswehaveseen,however,thereismuchmoretothesemarksthanisapparent.Aslongascaptiveslavesretainedtheirservilestatus—andthisoftenlastedtheirwholelives—suchbodilymarkingsidentifiedthemasdifferentandinferior. In contrast to the bodilymarkings inflicted in initiation rites,whicharemeanttomarkyoungstersasbelongingtotheirsocieties,theseothermarkswereaimedatunderliningthesocialdistanceexistingbetweenmasters and subordinates. Paraphrasing Clastres (1998a:184), it couldthusbearguedthatritualsofenslavementandmarkersofservitudewereaimedatnotifyingcaptivesinunambiguoustermsthat“You are not one of us, and you should never forget it.”Thus,ratherthanbeingameanstoensuresocialequalityandtorejectauthoritariannotionsofpower,hierarchy,andsubmission,asClastres(1998a:188)hasargued,inslavingsocietiesbodymarksservedthedoublepurposeofsignalingsomepeopleasequals,andothersassubordinates.

18

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 165

Inbothcases,thesymbolicmodificationofthebodyconstitutesakeyelementinwhatViveirosdeCastro(1979)callsthe“fabricationofbodies,”andSeegeretal.(1979:4)the“socialproductionofpeople.”Butwhereasinitiationritualsproducepeoplelikeus,thatis,equals,theimpositionofmarkersofservitudeservethepurposeofrepersonifyingthedepersonifiedcaptivesasaliensubordinates,thusinstitutionalizingtheirinequalityandmarginality. In theprocess,however, the impositionofsuchmarkers—someofwhichweremeant to stress theirdifferenceand some to stresstheirsimilarity—producedasocialhybrid, that is,peopledifferentfromus,butintegratedtooursocietyassubordinates. It is inthissensethatPattersoninsiststhatslaveshadthe“liminalstatusoftheinstitutionalizedoutsider”(1982:46).

CONCLUSIONS

Thediscussionaboveshoulddispelanyideathatthehandlingofwarcaptivesintheslavingsocietiesexaminedinthisessayisinanywaysimilarto that found among the ancientTupinambá (Carneiro da Cunha andViveirosdeCastro1985)or,more recently, among theTxicão (Menget1988),Matis(Erikson1993),orParakanã(Fausto2001).Thesecaptiveswereneithermeanttobeexecutedgloriouslyincannibalisticrituals,nortobeswiftlyassimilatedintotheircaptors’societies.Onthecontrary,theyweremarkedlinguisticallyandphysicallyasbothcaptivesandservants,astatusthatoftenpersisteduntiltheendoftheirlivesand,insomecases,waseventransmittedtotheirchildren(Santos-Granero,inpress). The analysis of the terms used by Amerindian slaving societies todesignate subordinate or dependent people allows us to draw anotherimportantconclusion. Almost invariably,thenativetermstranslatedbyEuropeanauthorsas“slave”wouldbebettertranslatedas“captive.”TheKalinagotámon,theConiboyádta,andtheGuaicurúnibotagiallconveythe notion of “someone seized in war, hunting or fishing,” that is, thenotionof“prey.”Theyalsoimplynotionsof“inferiority”and“servitude,”whichwouldexplainwhyEuropeansrapidlyequatedthesenativetermstotheirconceptof“slave.”7WhetherornotthesecaptivescanbeanalyticallyconsideredasslavesissomethingthatIaddressinanotherwork(Santos-Granero, in press). Here I stress that apart from these basic terms,Amerindianslavingsocietieshadarichvocabularytodescribesituationsofsubordinationandextremedependency. Itshouldalsobenotedthatinalltheaboveexamples,slavingsocietiessingledoutspecificneighboringpeoplesasenemiesandpotentialcaptives.Theydidsobyreferringtothembytermsthatbroughttomindnotionsof

19

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

166 Fernando Santos-Granero

inferiority,enmity,andservility.TheenemiesandpotentialcaptivesoftheKalinago,Conibo,andGuaicurú,weretheLokono,interfluvialPano,andGuanárespectively.Thissuggeststhatmembersofslavingsocietiessawtheirpreferredenemiesasmarkedwiththestigmaofservitudeevenbeforetheywereactuallydefeatedandsubjugated.Ushique,alatenineteenth-centuryConiboheadman,offeredaninterestingrationaleforthisparticularconception.Heasserted:“Cashibo[Uni]aremostlyourmaroonservantswhohave takento thewoods; theyspeakour language,althoughbadly,andwegofromtimetotimetoretrievetheiroffspringastheyreproduce”(Stahl1928[1895]:150).SimilarnotionsarepresentamongtheGuaicurú(Serra1845[1803]:204),indicatingthatAmerindianslavingsocietiessawtheirpreferredenemiesasslave-breedingorservant-breedingpopulations.Ifthisisthecase,themarkersofservitudeimposedonwarcaptivesduringritualsofenslavementwouldonlybeaconfirmationofapresumedandpreexisting“natural”condition.Theymark,however,animportantchangeofstatus,thatis,thepassagefrom“virtual”to“actual”slave. Indeed,intropicalAmericathereinforcementthroughavarietyofritualmechanismsofthesocialdistanceseparatingmastersfromsubordinates—whethercaptivepeople,servantgroups,ortributarypopulations—seemsto have been only a way of giving material expression to what captorsviewed as an original, almost essential, dissimilarity. The marking ofthebodiesofcaptives,whetheractuallyorsymbolically,byimpositionordefault,setthemapartasless-than-humanandinferiorforeigners.Thisistrueeveninthosecasesinwhichthemarkingsimposedwerethoseofthecapturingsociety,sincetheywerealwaysslightlydeficient—shorterhairbangs,cruderfacialdesigns,andsoon. Torture, the essence of initiation rituals according to Clastres(1998a:182),showsitsdarksideinthecontextofAmerindianritualsofenslavement. Insteadofbeing away tomark and celebrate initiates asequal,fullmembersoftheirsocieties,itbecomesameansformarkingwarcaptives painfully and indelibly as inferior, subordinatemembers of thesocietyoftheircaptors. Insuchcontexts,theinscriptionofthebodyisnotaconditionforthe“socialproductionofpeople”(Seegeretal.1979:4),butratherforthesocialproductionof“nonpeople,”thatis,ofsociallydeadslaves. ThewidespreadAmerindiannotionsthatenemypeoplesarelessthanhuman,thattheysharetraitswithanimalspecies,orthattheyrepresenta different, lesser kind of humanity, coincided with European views ofIndians as animals. Such notions facilitated opportunistic alliances,between European slavers and slaving societies, to subjugate weakerindigenouspeoples.ThiswasthecaseofKalinago,Conibo,andGuaicurú

20

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 167

peoples—butalsoofMundurucú,Tupinambáandothernonslaveholdingcapturingsocieties. Thecasesmentionedabovecollectivelyprovideagoodexampleofhowapparently similarAmerindianandEuropeanconceptionsandpracticesconspiredtobringforthanewreality(seeWhitehead2003:x).Membersof Amerindian slaving societies viewed Europeans as sharing theirwarriorvalues,notionsofsuperiority,andcontemptforweaker,perhapsless bellicosepeoples. Theybelieved that an alliancewith themwouldbenefit both. It is doubtful that they suspected—at least in the initialstages—thatEuropeantreatmentofwarcaptiveswasinanywaydifferentfromtheirown. Even less so, thatEuropeansconsideredall Indiansasalmostanimals,andthus,withthepassageoftime,theythemselveswouldbecomethesubjectofEuropeanslaveraiding. There were, however, important differences between AmerindianandEuropeannotionsofslavery,nottheleastofwhichwaswhethertheyconceivedofslaveryasapermanentortemporalstatus.Althoughthroughthe use of linguistic expressions, physical markers and ritual gesturesAmerindianslavingsocietiesmarkedsubordinateseitherassociallydistantor as socially dead,not even themarkedly alienwar captiveswere everconsidered to be total outcasts. They had a defined status, played animportantrole,andeventuallycouldbeassimilatedintothesocietyoftheircaptors.Indeed,althoughthestatusofcaptiveslaveswaswelldefined,itwascertainlynotdefinitive. They,butmoreoften their children,couldbecome assimilated to their captors’ society once they had adopted thelanguageandmoresoftheirmasters,thatis,whentheybecame“civilized.”Such processes of “civilization”/“domestication” involved mind/bodymodificationseffectuatedthroughthesharingofmemoriesandsubstances,such as those described for present-day Panoan peoples (Frank 1990;Lagrou2006).Butthechangeofstatuswasalsomarkedlinguisticallyandimprintedonthebodiesofformercaptives.Thus,wemayconcludethatrather thanafixed status, slaverywas a socialprocess innative tropicalAmerica.Physicallymarkedasbothoutsidersandinsiders,thestatusofcaptiveslaveswasliminalandtransient,andperhapscouldeventuallyleadtofullassimilation.

NOTES

1.ByservitudeIunderstandallformsofinstitutionalizedsubjectionrelyingmainly,butnotexclusively,onphysicalcoercion. Whereasslavery isa formofservitude,notallformsofservitudefallunderthecategoryofslavery.Incontact-time tropical America other common forms of servitude adopted the form of

21

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

168 Fernando Santos-Granero

attached servant groups and subordinated tributary populations (see Santos-Granero,inpress). 2.By“timeof contact” Imean the longperiod characterizedbymultiple,intermittent,andtemporallyvariablephasesofinteractionbetweenAmerindianandEuropeanpeoplesthatculminatedintheconquestofnativepeoplesandthesettlementoftheirlands.Inotherwords,itreferstotheperiodinwhichagivenindigenoussocietycameincontactwithEuropeans,butstillretaineditspoliticalautonomy. 3. In tropical America, “endoslavery,” that is, the enslavement of peoplebelongingtoone’sownethnicgroup,isonlyfoundinstatesocietiessuchastheAztecs,oftenundertheformofdebtslavery(Davies1973:81,93). 4.Ihaveconsultedtheearliestsourcesavailableforeachcase,aswellasothersourcesproducedduringtheperiodinwhichthesocietiessurveyedhadnotyetbeenconqueredbyEuropeancolonialpowers.Becausethesocietiesinthesamplewerelocatedinareasdisputedbymorethanoneofthesepowerstheywereabletoretaintheirautonomyforverylongperiods.Inaddition,becausecolonialpowerswere competing to subject these indigenous societies, they produced abundantdocumentation on their cultural practices. The quality of these sources variessignificantly.Inordertoensureamaximumofreliability,hereIhaveconsideredonlydataverifiedbymorethanoneindependentsource.Whenthisisnotso,Iindicateitinthetext. 5.Inallhistoricalreferencesincludedinthetext,thedateinbetweensquarebracketsindicatesthetimeinwhichtheauthorsmadetheirobservations,ratherthanthatofthefirsteditionoftheirwork,exceptwherethedateinbracketsinthe“referencescited”sectionspecificallyindicatestheoriginaldateofanearlierpublishedversionofthecitedtext. 6.ItshouldbenotedthatKalinagoalsohadatermforservantsnotcapturedinwar,or“hiredservants,suchastheChristianshave”:nabouyou(Rochefort1666[1658]:Appendix;Breton1666:362).SuchlinguisticdistinctionshoulddispelthenotionthatEuropeanchroniclersmistookKalinago“servants”for“slaves.” 7. Among the Northwest Coast and Plateau Indians, terms translated byEuropean chroniclers as “slave” also carried a connotation of inferiority (RubyandBrown1993:27).Klamathscalledcaptiveslaves“loadcarriers”;Yurokscalledthem“bastards;”whereasYakinacalledthem“insignificantpeople.”

REFERENCES CITED

Alès,Catherine 1981 “Les tribus indiennes de l’Ucayali au XVIe siècle.” Bulletin de

l’Institut Français d’Etudes Andines10(3–4):87–97.Anonymous 1927 “Diccionariocunibo-castellanoycastellano-cunibo.”InHistoria de

las misiones franciscanas y narración de los progresos de la geografía en el oriente del Perú,1619–1921.BernardinoIzaguirre,editor,13:391–474.Lima:TalleresGráficosdelaPenitenciaría.

22

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 169

Anonymous 1988 Un flibustier français dans la mer des Antilles en 1618–1620. Clamart:

EditionsJean-PierreMoreau.Boggiani,Guido 1945 Os Caduveo.SãoPaulo:LivrariaMartinsEditôra.Basso,EllenB. 1988 [orig.1973]The Kalapalo Indians of Central Brazil. ProspectHeights,

IL:WavelandPress.Breton,RaymondGuillaume 1665 Dictionaire caraibe-françois.Auxerre:GillesBouquet. 1666 Dictionaire françois-caraibe.Auxerre:GillesBouquet. 1978 Relations de l’Ile de la Guadeloupe.Basse-Terre:Sociétéd’Histoirede

laGuadeloupe.(TomeI)CarneirodaCunha,ManuelaL.andEduardoB.ViveirosdeCastro 1985 “Vingançaetemporalidade:OsTupinamba.”Journal de la Société des

Americanistes71:191–208.Castelnau,Francisde 1850–59Expédition dans les parties centrales de l’Amérique du Sud.Paris:Chez

P.Bertrand.(17volumes).Chanca,DiegoAlvarez 1978 “A letteraddressed to theChapterofSevillebyDr.Chanca.” In

Four Voyages to the New World. Letters andSelectedDocuments.R.H.Major,editor,pp.18–68.Gloucester,MA:PeterSmith.

Chevillard,André 1659 Les Desseins de son Eminence de Richelieu pour l’Amerique. Rennes:

ChezJeanDurand.Clastres,Pierre 1998a [orig.1974]“OfTortureinPrimitiveSocieties.”InSociety Against

the State: Essays in Political Anthropology, pp.177–188.NewYork:ZoneBooks.

1998b [orig. 1974] “Exchange and Power: Philosophy of the IndianChieftainship.” In Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology,pp.27–47.NewYork:ZoneBooks.

Columbus,Ferdinand 1992 The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his Son Ferdinand.

NewBrunswick,NJ:RutgersUniversityPress.Coma,Guglielmo 1903 “TheSyllacio-ComaLetter.”InChristopher Columbus, His Life, His

Works, His Remains as Revealed by Original Printed and Manuscript Records,Volume2. JohnBoydThacher,editor,pp.223–262.NewYork:G.P.Putnum’sSons.

Condominas,Georges(editor) 1998 Formes extrêmes de dépendance: Contributions à l’étude de l’esclavage

en Asie du Sud-est. Paris:Editiondel’EcoledesHautesEtudesenSciencesSociales.

23

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

170 Fernando Santos-Granero

Cúneo,Miguelde 1928 “DeNovitatibusInsulariiOcceaniHeperiiRepertataaDonXpoforo

Columbo,Genuensi.”InCristóbal Colón, Genovés. RómuloCúneo-Vidal,Apéndice,pp.277–301.Barcelona:CasaEditorialMaucci.

Davies,Nigel 1973 The Aztecs: A History.London:MacmillanLtd.DeBoer,WarrenR. 1986 “Pillage and Production in the Amazon: A View Through the

Conibo of the Ucayali Basin, Eastern Peru.” World Archaeology18(2):231–246.

DelasCasas,Bartolomé 1986 Historia de las Indias.Caracas:BibliotecaAyacucho.(3volumes).DuTertre,Jean-Baptiste 1654 Histoire Generale des Isles de S. Christophe, de la Guadeloupe, de la

Martinique, et autres dans l’Amérique.Paris:JacquesLanglois.Erikson,Philippe 1993 “Une nébuleuse compacte: le macro-ensemble pano.” L’Homme

126–128,33(2–4):45-58.Fausto,Carlos 1999 “Of Enemies and Pets: Warfare and Shamanism in Amazonia.”

American Ethnologist26(4):933–956. 2001 Inimigos fiéis: História, Guerra e xamanismo na Amazônia.SãoPaulo:

EditoradaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo.Florence,Hercules 1941 Viagem fluvial do Tietê ao Amazonas, de 1825 a 1829. São Paulo:

EdiçõesMelhoramentos.Frank,ErwinH. 1990 “PacificaralhombremalooescenasdelahistoriaaculturativaUni

desdelaperspectivadelasvíctimas.”Amazonía Indígena10(16):17–25.

Gregor,Thomas 1980 Mehinaku: The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village.

Chicago:TheUniversityofChicagoPress.Hajda,YvonneP. 2005 “Slavery in the Greater Lower Columbia Region.” Ethnohistory

52(3):563–588.Heckenberger,MichaelJ. 2003 “TheEnigmaof theGreatCities:BodyandState inAmazonia.”

Tipití1(1):27–58.Hugh-Jones,Stephen 1988 The Palm and the Pleiades: Initiation and Cosmology in Northwest

Amazonia. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress.Huxley,Francis 1957 Affable Savages: An Anthropologist among the Urubu Indians of Brazil.

NewYork:TheVikingPress.

24

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 171

Jolís,José 1972 Ensayo sobre la historia natural del Gran Chaco.Resistencia,Chaco:

UniversidadNacionaldelNordeste.Labat,Jean-Baptiste 1724 Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l’Amérique. Haye: Pierre Husson,

ThomasJohnson,PierreGosse,JeanVanDuren,RutgertAlberts,andCharlesleVier.(2volumes).

Lagrou,Elsje inpress “Laughing at Power and the Power of Laughter in Cashinahua

NarrativeandPerformance.”Tipití.Leland,Donald 1997 Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America.Berkeley:

UniversityofCaliforniaPress.Lévy-Bruhl,Henri 1931 “Théoriedel’esclavage.”Revue Générale du Droit 55(1):1–17.Lévi-Strauss,Claude 1993 “Unautreregard.”L’Homme 126–128,33(2–4):7–10.Lorant,Stefan(editor) 1965 The New World. The First Pictures of America, Made by John White and

Jacques Le Moyne and Engraved by Theodore de Bry, With Contemporary Narratives of the French Settlements in Florida, 1562–1565, and the English Colonies in Virginia, 1585–1590. NewYork:Duell,SloanandPearce.

Lowie,RobertH. 1948 “Social and Political Organization of the Tropical Forest and

MarginalTribes.”InHandbook of South American Indians.Volume 5: The Comparative Ethnology of South American Indians. JulianH.Steward, editor,pp.313–350. Washington,DC:SmithsonianInstitution,BureauofAmericanEthnologyBulletin143.

Lozano,Pedro 1733 Descripción chorographica del terreno, ríos, árboles, y animales delas

dilatadísimas provincias del Gran Chaco. Córdoba: Colegio de laAssumpción,porJosephSantosBalbàs.

MacLeod,WilliamChristie 1928 “Economic Aspects of Indigenous American Slavery.” American

Anthropologist 30(4):632–650.Marcoy,Paul 1869 Voyage a travers l ’Amérique du Sud de l’Océan Pacifique a l’Océan

Atlantique.Paris:LibrairiedeL.HachetteetCie.(2volumes).Marqués,Buenaventura 1931 “VocabulariodelalenguaCuniba.”Revista Histórica9(2–3):117–

195.Mauss,Marcel 1936 “Lestechniquesducorps.”Journal de Psychologie 32(3–4).Meillassoux,Claude 1975 L’esclavage en Afrique précolonial.Paris:FrançoisMaspero.

25

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

172 Fernando Santos-Granero

Menget,Patrick 1988 “Notessurl’adoptionchezlesTxicãoduBrésilCentral.”Anthropologie

et Sociétés12(2):63–72. 1996 “De l’usage des trophées en Amérique du Sud: Esquisse d’une

comparaisonentre lespratiquesnivaclé (Paraguay) etMundurucú(Brésil).”Systèmes de Pensée en Afrique Noire14:127–143.

Morin,Françoise 1998 “Los Shipibo-Conibo.” In Guía etnográfica de la alta amazonía,

Volumen 3: Cashinahua, Amahuaca, Shipibo-Conibo. FernandoSantosGraneroandFredericaBarclay,editors,pp.275–435.Quito:SmithsonianTropicalResearchInstitute/InstitutFrançaisd’EtudesAndines/Abya-Yala.

Murphy,RobertF.andBuellQuain 1966 The Trumai Indians of Central Brazil. Seattle: University of

WashingtonPress.Nimuendajú,Curt 1939 The Apinayé.Washington,DC:TheCatholicUniversityofAmerica

Press.NúñezCabezadeVaca,Alvar 1585 “Comentarios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, adelantado y

gobernador de la provincia del Río de la Plata.” In La relación y comentarios del gobernador... de lo acaecido en las dos jornadas que hizo a las Indias.AlvarNúñezCabezadeVaca,pp.lvii-clxiii.Valladolid:FranciscoFernándezdeCórdova.

Oakdale,Suzanne 2005 I Foresee My Life: The Ritual Performance of Autobiography in an

Amazonian Community. Lincoln:UniversityofNebraskaPress.Onions,C.T.(editor) 1974 The Oxford Universal Dictionary Illustrated. Oxford: Clarendon

Press.Ordinaire,Olivier 1887 “LessauvagesduPérou.”Revue d’Ethnographie6:265–322.Oviedo,GonzaloFernándezde 1851 Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra-firme del mar

océano.Madrid:ImprentadelaRealAcademiadelaHistoria.Patterson,Orlando 1982 Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study.Cambridge:Harvard

UniversityPress.Pétesch,Nathalie 2000 La pirogue de sable: Pérennité cosmique et mutation sociale chez les

Karajá du Brésil central. Paris:Peeters.Prado,FranciscoRodriguesdo 1839 “HistoriadosIndiosCavalleirosoudanaçãoGuaycurú.”Revista do

Instituto Historico e Geographico do Brazil1(1):25–57.Rochefort,Charlesde 1666 The History of the Caribby-Islands. London: Printed by J.M. for

ThomasDringandJohnStarkey.

26

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4

Amerindian Torture Revisited 173

Roe,PeterG. 1982 The Cosmic Zygote: Cosmology in the Amazon Basin.NewBrunswick,

NJ:RutgersUniversityPress.Ruby,RobertH.andJohnA.Brown 1993 Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest.Spokane,WA:TheArthur

H.ClarkCompany.SánchezLabrador,José 1910–17El Paraguay Católico. BuenosAires:ImprentadeConiHermanos.

(3volumes).Santos-Granero,Fernando inpress Vital Enemies: Slavery, Predation and the Amerindian Political

Economy of Life.Schmidel,Ulrico 1749 “Historia ydescubrimientodeelRíode laPlata yParaguay.” In

Historiadores primitivos de las Indias Occidentales. AndrésGonzálezdeBarcia,editor,Volume3.Madrid.

Seeger,Anthony 1981 Nature and Society in Central Brazil: The Suya Indians of Mato Grosso.

Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversityPress.Seeger,Anthony,RobertodaMatta,EduardoViveirosdeCastro 1979 “A construção da pessoa nas sociedades indígenas brasileiras.”

Boletim do Museu Nacional, Nova Serie28:2–19.Serra,RicardoFrancodeAlmeida 1845 “ParecersobreoaldeamentodosIndiosUaicurúseGuanás,coma

descripçãodosseususos,religião,estabilidade,ecostumes.”Revista do Instituto Historico Geographico Brazileiro7(26):204–212.

Stahl,EuricoG. 1928 “La tribu de los Cunibos en la region de los lagos del Ucayali.”

Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima 45(2):139–166.Steward,JulianH.andLouisC.Faron 1959 Native Peoples of South America. NewYork:McGraw-HillBookCo.

Inc.Taussig,Michael 1999 Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford:

StanfordUniversityPress.Taylor,CharlesEdwin 1888 Leaflets from the Danish West Indies: Descriptive of the Social, Political,

and Commercial Condition of these Islands.London:WilliamDawsonandSons.

Techo,Nicolásdel 1897 Historia de la Provincia del Paraguay de la Compañía de Jesús.Madrid:

A.deUribeyCia.(5volumes).Turner,Terence 1995 “SocialBodyandEmbodiedSubject:Bodiliness,Subjectivity,and

Sociality among theKayapo.” Cultural Anthropology 10(2):143–170.

27

Amerindian Torture Revisited: Rituals of Enslavement and Markers

Published by Digital Commons @ Trinity, 2005

174 Fernando Santos-Granero

Unger,Elke 1972 “ResumenetnográficodelVocabularioEyiguayegi-MbayádelP.José

SánchezLabrador.”InFamilia Guaycurú. BranislavaSusnik,editor,Volume3,Part6.Asunción:MuseoEtnográfico“AndrésBarbero.”(3volumes).

Vaughan,JamesH. 1977 “Makafur:ALimbicInstitutionoftheMargi.”InSlavery in Africa:

Historical and Anthropological Perspectives. Suzanne Miers andIgor Kopytoff, editors, pp. 85–102. Madison:The University ofWisconsinPress.

ViveirosdeCastro,Eduardo 1979 “Afabricaçãodocorponasociedadexinguana.”Boletim do Museu

Nacional32:40–49. 1992 From the Enemy’s Point of View: Humanity and Divinity in an

Amazonian Society.Chicago:TheUniversityofChicagoPress.Wagley,CharlesandEduardoGalvão 1949 The Tenetehara Indians of Brazil: A Culture in Transition.NewYork:

ColumbiaUniversityPress.Whitehead,NeilL. 1988 Lords of the Tiger Spirit: A History of the Caribs in Colonial Venezuela

and Guyana, 1498–1820. DordrechtRI:ForisPublications. 2003 Introduction. In Histories and Historicities in Amazonia. Neil L.

Whitehead, editor, pp. vii–xx. Lincoln: University of NebraskaPress.

28

Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America

http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/tipiti/vol3/iss2/4