A validation study of the Italian Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of A validation study of the Italian Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire validation studyA. FRASER* , B. C. DELANEY* , A. C. FORD� , M. QUME* & P. MOAYYEDI*

*Department of Primary Care and

General Practice, Primary Care Clin-

ical Sciences Building, University of

Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birming-

ham; �Centre for Digestive Diseases,

Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds, West

Yorkshire, UK

Correspondence to:

Dr B. C. Delaney, Department of

Primary Care and General Practice,

Primary Care Clinical Sciences

Building, University of Birmingham,

Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK.

E-mail: [email protected]

Publication data

Submitted 9 August 2006

First decision 24 August 2006

Resubmitted 9 December 2006

Accepted 13 December 2006

SUMMARY

BackgroundAssessment of symptoms should be the primary outcome measure indyspepsia clinical trials. This requires a reliable, valid and responsivequestionnaire that measures the frequency and severity of dyspepsia.The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire fulfils these characteristics, but islong and was not designed for self-completion, so a shorter question-naire was developed (the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire).

AimTo assess the acceptability, interpretability, internal consistency, reliab-ility, validity and responsiveness of the Short-Form Leeds DyspepsiaQuestionnaire in primary and secondary care.

MethodsUnselected primary and secondary care patients completed the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire. Test–retest reliability was assessed

after 2 days. Validity was measured by comparison with general practi-tioners’ diagnosis. Sensitivity analysis and logistic regression wereemployed to determine the most valid scoring system. Responsivenesswas determined before and after treatment for endoscopically provendisease.

ResultsThe Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire was administered to 388primary care and 204 secondary care patients. The Pearson coefficientfor test–retest reliability was 0.93. The Short-Form Leeds DyspepsiaQuestionnaire had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 75%. Ahighly significant response to change was observed (P < 0.005).

ConclusionsThe Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire is a reliable, valid andresponsive self-completed outcome measure for quantifying the fre-quency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms, which is shorter and moreconvenient than the Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

ª 2007 The Authors 477

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03233.x

INTRODUCTION

Dyspepsia is a common condition, and one that con-

sumes considerable resources in both investigation and

treatment and of which there is still a great deal of

uncertainty regarding its management.1, 2 As a result,

a number of ‘cost-effectiveness’ randomized trials of

dyspepsia management strategies have been conduc-

ted. One difficulty for researchers has been choosing

an appropriate outcome measure as definitions of dys-

pepsia have changed over the years, and cost-effect-

iveness studies require that the ‘effect measure’ is not

contaminated by ‘resource use questions’ such as visits

to a doctor. Multidimensional scales that also assess

quality of life are particularly problematic, as there are

better validated quality of life measures that have gen-

eralizability over other disease areas (e.g. Health Util-

ity Index3 and EQ-5D4). As there is no ‘absolute’

definition of dyspeptic symptoms we rely on question-

naires that have established psychometrics.5 Dyspepsia

symptoms can be assessed by measuring either fre-

quency or severity. The frequency of symptoms has

been found to correlate more closely with a clinical

diagnosis of dyspepsia than severity, indicating that

frequency may be more valid for pragmatic studies.6

In gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD), severity

of symptoms correlates more closely with oesophagitis

cure than frequency, indicating that severity may be

more responsive to change.7 Measuring both frequency

and severity of dyspepsia symptoms may improve both

validity and responsiveness to change of an instru-

ment compared with measuring either alone.6–9 A final

important factor for cost-effectiveness trials is that the

instrument is suitable for self-completion by the sub-

ject, in terms of length and ease of comprehension.

For clinical trials based in a primary care setting,

the outcome measure should have been validated in a

primary care population, where the aetiology, preval-

ence and severity of patients’ symptoms may differ to

those from secondary or tertiary care populations.10

In addition, outcome measures should be able to

distinguish between patients suffering from predomin-

antly ulcer-like symptoms (epigastric pain) or reflux

symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation); some evi-

dence suggests that predominant ulcer-like or reflux

symptoms do not reliably predict endoscopic diagnosis

of oesophagitis or ulcer, respectively.11

In a recent review of symptom-based outcome

measures for dyspepsia and GERD trials 37 studies

were identified describing 26 questionnaire outcome

measures.5 Twelve assessed symptoms only, and 14

were multidimensional. Of the unidimensional ques-

tionnaires, only two assessed both frequency and

severity of dyspepsia and had proven reliability, valid-

ity and responsiveness. The Reflux Disease Diagnostic

Questionnaire (RDQ) is an excellent measure for GERD,

but is not validated to assess dyspepsia.11 The Leeds

Dyspepsia Questionnaire (LDQ)10 was the only fully

validated unidimensional instrument to assess both

frequency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms.

Although the LDQ is a useful unidimensional outcome

measure for dyspepsia, it has three main disadvanta-

ges. It is researcher administered (not self-completed),

it is long (nine pages) and has a long reference time

frame (6 months). The aim of this study was to valid-

ate a shortened and revised the LDQ as a suitable

measure for dyspepsia trials.

METHODS

Questionnaire development

The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

(SF-LDQ) was developed by shortening and revising

the previously validated LDQ.10 The LDQ contained

eight questions relating to dyspeptic symptoms, and

one question about the most troublesome symptom for

the patient. The SF-LDQ contained the four questions

from the LDQ which had the greatest validity com-

pared with dyspepsia diagnosis by general practition-

ers (GP) and gastroenterologists.12 Each question

comprised two stems concerning the frequency and

severity of each symptom during the last 2 months.

This time frame was a balance between reducing recall

bias (requiring a shorter time frame) and maximizing

data capture without unnecessary respondent burden

(requiring a longer time frame).9 The SF-LDQ also con-

tained a single question concerning the most trouble-

some symptom experienced by the patient to enable

categorization of patients on the basis of predominant

heartburn or epigastric pain.

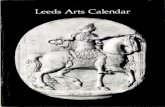

The SF-LDQ was redesigned to increase its accepta-

bility, interpretability and feasibility of self-comple-

tion. The questions were arranged to fit onto a single

A4 page, with shaded boxes around the questions and

tick boxes for responses. Short summaries of the

symptoms were included to reduce ambiguity, and dia-

grammatic representations of epigastric pain and

heartburn were added to ensure understanding of these

symptoms.

478 A. FRASER et al.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

The SF-LDQ was piloted initially using six rounds of

peer review and feedback. Version 6 of the question-

naire was piloted using a sample of 67 consecutive

primary care patients. Several modifications of the for-

mat were made and instructions were included on the

questionnaire as a result. The final version of the

SF-LDQ is attached (Figure 1).

Evaluation of the SF-LDQ

The characteristics of the questionnaire were exam-

ined using patient populations in both primary care,

with a relatively low prevalence of disease, and sec-

ondary care, with a high prevalence of dyspepsia.

The primary care population consisted of consecutive

patients aged 18–65, presenting to two inner city

general practices in Birmingham (deprivation ranks of

386 and 841 of 32 48213) with any condition. As

dyspeptic symptoms affect around 28% of the popu-

lation,14, 15 we did not specifically select patients

with dyspepsia. The secondary care study population

consisted of unselected patients aged 18 and over,

attending for endoscopy at the Leeds General Infirm-

ary. Patients were excluded if they were incapable of

giving informed consent, or if they could not speak

or read English.

Patients were asked to participate in the study on

arrival at their GP’s surgery or the endoscopy suite.

A trained researcher obtained informed consent.

Patients self-completed the SF-LDQ and an assessment

sheet containing questions about the acceptability and

interpretability of the questionnaire. These were sealed

in an envelope before seeing the GP or gastroenterolo-

gist, who made a blind assessment of the whether the

Figure 1. The Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (SF-LDQ).

DYSPEPS IA QUESTIONNAIRE VAL IDAT ION STUDY 479

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

patient suffered with dyspepsia and recorded this on

the preprinted envelope along with demographic infor-

mation. Validity was established by comparing the

SF-LDQ score with the presence or absence of dyspep-

sia as diagnosed by the GP or gastroenterologist.

All primary care participants were asked to complete

a second SF-LDQ after 2 days to assess test–retest reli-

ability. Within the secondary care population, patients

identified as having oesophagitis or peptic ulcer dis-

ease during endoscopy were asked to complete a sec-

ond SF-LDQ 2 months later after receiving treatment

of proven efficacy (proton pump inhibitor therapy

and/or Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy). This

enabled assessment of the SF-LDQ’s responsiveness to

change in conditions with evidence-based treatments.

Freepost envelopes were used to enhance response

rates, but non-responders to the second questionnaire

were not contacted.

Data were entered onto Microsoft Excel 2000 before

conversion into SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, v10 for

analysis. Logistic regression analysis was performed

using Generalized Linear Interactive Modelling, Royal

Statistical Society (GLIM) to determine the most valid

scoring system for the questionnaire. Statistical signi-

ficance was determined where P < 0.05. Ethical

approval was obtained for South Birmingham, West

Birmingham and Leeds, UK.

RESULTS

Population

A total of 592 patients were enrolled into the study, 388

patients from primary care and 204 patients from sec-

ondary care. Out of these, 361 (61%) were female and

231 (39%) were male. Ages for the primary care patients

ranged from 18 to 65, and for secondary care, 18–81.

Fifty-five questionnaires (9%) had one or more missing

responses and were excluded from the final analysis, as

a summed score could not be calculated. Score analysis

was therefore performed on 375 patients from primary

care and 162 patients from secondary care.

Interpretability and acceptability

Five hundred and eighty-six participants from primary

and secondary care completed at least one question

concerning the interpretability and acceptability of the

SF-LDQ. Overall, 97% found the questionnaire easy to

read, 95% found it easy to interpret and 94% thought

the layout was sufficiently clear.

Endorsement frequencies (the proportion of respond-

ents who chose each response category to a question)

were calculated for each response category to every

question using combined data from primary and sec-

ondary care. Every response category had an endorse-

ment frequency of >5%, except for regurgitation

severity ‘more than daily’ (Table 1). The distribution of

responses to each of the questions about symptom fre-

quency and severity were positively skewed, reflecting

the inclusion of the 278 participants from primary care

(47% of all participants) who did not have dyspepsia

according to their GPs diagnosis.

Non-response to questions regarding symptom fre-

quency occurred with 1% or less of participants, indica-

ting that this part of the questionnaire was acceptable

and interpretable. However, there was no response to

questions regarding symptom severity in around 5% of

cases, indicating that this part of the questionnaire may

have been less acceptable or interpretable.

Table 1. Endorsement frequencies for each response category of the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire

Symptom

Response category (%)

Notat all

Less thanmonthly

Between monthlyand weekly

Between weeklyand daily

Morethan daily

Noresponse

Indigestion frequency 35 16 15 16 17 1Heartburn frequency 39 18 15 15 13 0.8Regurgitation frequency 43 21 14 14 8 0.5Nausea frequency 38 23 16 14 9 1Indigestion severity 45 12 13 16 8 5Heartburn severity 50 11 15 12 7 5Regurgitation severity 56 13 12 10 4 5Nausea severity 46 18 12 11 6 6

480 A. FRASER et al.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for combined primary

and secondary care patients was 0.90, representing a

high level of internal consistency. The item-total cor-

relation for each question ranged from 0.57 to 0.75,

suggesting that each question was independently asso-

ciated with the total questionnaire score and that all

questions were measuring different aspects of the same

condition.

Test–retest reliability

In the primary care sample, 151 of 375 patients (40%)

returned a fully completed second questionnaire after

at least 2 days. Pearson’s correlation coefficient

between the first and second summed total scores was

0.93, representing a high degree of reliability on

re-testing the questionnaire.

Validity

Concurrent validity was established using the primary

care population and divergent validity was examined by

comparing the primary and secondary care populations.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the

SF-LDQ score with the GPs’ opinion of whether the

patient had dyspepsia, expressed as a dichotomous

‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. Altogether 101 patients (27%)

were diagnosed as suffering with dyspepsia, 278

patients (73%) had no dyspepsia. Nine participants out

of 375 with fully completed questionnaires did not

receive a clinical assessment of dyspepsia by their GP,

so 366 primary care patients were analysed to deter-

mine concurrent validity.

Sensitivity analyses

SF-LDQ scores were calculated using five different

methods to evaluate which produced the most valid

assessment of dyspepsia. These methods were:

1 a summed total score of the frequency and sever-

ity responses for each symptom (range: 0–32);

2 a summed score of the frequency responses for

each symptom (range: 0–16);

3 a summed score of the severity responses for each

symptom (range: 0–16);

4 a categorized score of the single most frequent

symptom (range: 0–4) and

5 a categorized score of the single most severe

symptom (range: 0–4).

Categorized scores were calculated by rating the sin-

gle most frequent or severe symptom from 0 (not at

all) to 4 (once a day or more). Scoring systems 1–3 are

more practical and feasible to administer as they

require simple addition. Scoring systems 4 and 5 are

more complex, but may be more valid as they are

based on the Rome criteria for assessing the presence

of dyspepsia.16

For each scoring system, a Receiver Operating Char-

acteristics (ROC) curve was plotted against the GPs’

diagnosis to determine the most sensitive and specific

point on the scale. The first point on each ROC curve

where sensitivity was greater than specificity was

selected as the ‘cut-off’ for diagnosing the presence of

dyspepsia. This gave a dichotomous outcome of whe-

ther dyspepsia was present or absent for each scoring

system. Table 2 shows the area under the ROC curves

and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using differ-

ent scoring systems, together with the chosen cut-off

score, sensitivity and specificity for that system.

Although the summed frequency score produced a

slightly larger area under the ROC curve (0.83) com-

pared with the summed total score (0.82), this differ-

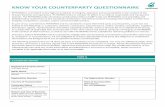

Table 2. Attributes of the five systems used to score the Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire in the primary carepopulation

Scoring system Area under curve (95% CI) ‘Cut-off’ score Sensitivity Specificity

1 Summed total score 0.82 (0.777–0.868) 7/32 77.3 73.22 Summed frequency score 0.83 (0.790–0.876) 4/16 86.0 66.23 Summed severity score 0.76 (0.700–0.817) 2/16 80.6 61.04 Categorized frequency score 0.79 (0.738–0.836) 2/4 86.1 59.75 Categorized severity score 0.73 (0.671–0.787) 1/4 84.2 45.7

DYSPEPS IA QUESTIONNAIRE VAL IDAT ION STUDY 481

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

ence was not statistically significant. The summed

total score was chosen as the preferred method of

scoring the questionnaire because this scoring system

had the greatest specificity, giving closer agreement

between the sensitivity and specificity, and it also had

a greater range of possible scores, allowing greater

precision.17 Figure 2 shows the ROC curve for the

summed total score.

Logistic regression analyses

Logistic regression analyses assessed the strength of

the scoring system’s association with the GPs’ diagno-

sis. All associations were strongly statistically signifi-

cant (P < 0.0005). The summed frequency score was

marginally the best predictor of GPs’ diagnosis. How-

ever, the difference between the summed total score

and the summed frequency score again was not statis-

tically significant.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing

the primary and secondary care populations using the

summed total scoring system. Figure 3 shows the

range of scores in the two populations. The difference

between these scores was highly statistically signifi-

cant using the Mann–Whitney U-test (P < 0.0005),

demonstrating that the SF-LDQ was able to discrimi-

nate between two populations with different preva-

lence of dyspepsia.

Responsiveness to change

Oesophagitis or peptic ulcers was found in 60 of the

162 patients who completed the first questionnaire

from the secondary care population following endo-

scopy. These patients were asked to complete a second

questionnaire following treatment of proven efficacy,

2 months after the endoscopy. This questionnaire was

returned by 47 patients (78%). Ten patients were

excluded due to missing data, leaving 37 patients eli-

gible for this analysis.

The number of patients with dyspepsia present and

absent according to the ‘cut-off’ identified by the sen-

sitivity analysis for the summed total score (seven of

32) was compared before and after treatment (Table 3).

Before treatment 89% of patients had dyspepsia com-

pared with 38% after treatment, which was highly sig-

nificant using the McNemar test (P < 0.005). The

standardized response mean for this change was 1.1,

suggesting a large degree of responsiveness.

1 - Specificity1.000.750.500.250.00

Sen

sitiv

ity1.00

0.75

0.50

0.25

0.00

Figure 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic curve for thesummed total score of the Short-Form Leeds DyspepsiaQuestionnaire. The lines show the most sensitive and spe-cific cut-off point for the scoring system.

Secondary carePrimary care

Sum

med

tota

l sco

re

34

30

26

22

18

14

10

6

2

–2

Figure 3. Box plot showing the distribution of Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire summed total scoresfor primary (n ¼ 375) and secondary care (n ¼ 162) pop-ulations. ‘Boxes’ show 25–75th centiles, with the horizon-tal line representing the mean. ‘Whiskers’ represent the5th and 95th centiles.

482 A. FRASER et al.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Predominant symptom analysis

The influence of the predominant (or most trouble-

some) symptom on the GPs’ diagnosis of dyspepsia

and SF-LDQ scores (total and summed frequency) was

assessed in the 364 primary care patients who comple-

ted this question and had a GP diagnosis. Four sub-

groups were identified reflecting the 1988 Working

Party definition of dyspepsia:18 those with predomin-

ant reflux-like symptoms (heartburn and regurgita-

tion); those with predominant ulcer-like symptoms

(epigastric pain); those with predominant dysmotility-

like symptoms (nausea) and those with no predomin-

ant symptom. The results are shown in Table 4.

The reflux-like and ulcer-like subgroups contained a

higher proportion of patients who were diagnosed with

dyspepsia by their GP and had higher mean question-

naire scores compared with the other subgroups. There

was little difference between the dyspepsia diagnoses

or questionnaire scores of those with predominant

reflux-like or ulcer-like symptoms, suggesting that dif-

ferentiating between these subgroups may not be clin-

ically relevant. There were insufficient numbers of

patients in each subgroup to determine the concurrent

validity of the questionnaire scores compared with

GPs diagnosis using ROC curves. As a result, the sensi-

tivity and specificity of the SF-LDQ for dyspepsia in

these subgroups could not be calculated.

The effect of excluding patients with predominant

reflux-like symptoms on the concurrent validity of the

SF-LDQ was assessed, to determine the effect of using

the Rome II definition instead of the 1988 Working

Party definition of dyspepsia. This gave an area under

the ROC curve of 0.83 for the summed frequency

score, which was almost identical to the area under

the curve for all patients, including those with

predominant reflux symptoms (0.82). This suggests

that the SF-LDQ predicts the diagnosis of dyspepsia in

a similar way whether or not patients with predomin-

ant reflux symptoms are included.

DISCUSSION

The SF-LDQ proved to be a sensitive and specific

measure, acceptable to patients and suitable for high

rates of self-completion. The SF-LDQ was responsive

to change and able to differentiate between popula-

tions with differing prevalence, demonstrating discri-

minant validity. Other dyspepsia questionnaires have

also been tested for discriminant validity19–21 provi-

ding additional evidence for the construct validity of

this instrument.

The summed frequency scoring system demonstrated

the greatest concurrent validity when analysed using

the area under ROC curves and logistic regression.

However, the difference in concurrent validity between

this scoring system and the summed total score was

not statistically significant. The summed total score

has a greater range of values (0–32) than the summed

frequency score (0–16), which gives greater precision.

Rates of non-response to questions about symptom

frequency were very low (0.5–1%), indicating that

these questions were acceptable. Rates of non-response

to questions about symptom severity were higher

(5–6%) indicating that these items were less interpreta-

ble or acceptable to a minority.

Table 3. Number of secondary care patients with dyspep-sia before and after treatment using the summed totalscore (n ¼ 37; ‘cut-off ’ point ¼ 7 of 32)

After treatment

TotalDyspepsiapresent

Dyspepsiaabsent

Before treatmentDyspepsia present 14 19 33Dyspepsia absent 0 4 4

Total 14 23 37

Values in bold indicate those partipants who had a changein dyspepsia status following treatment. No patients withoutdyspepsia developed symptoms following treatment, and 19patients with dyspepsia were ‘cured’ following treatment.This demonstrates that the questionnaire is responsive tochanges in symptoms.

Table 4. General practitioner (GP) diagnosis and Short-Form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire scores by symptomsubgroup

Symptomsubgroup

Numberof patients

GP diagnosis(percentagewith dyspepsia)

Mean totalscore

Reflux-like 92 48 11.4Ulcer-like 59 53 10.7Dysmotility-like 97 20 7.9None of these 116 2 1.1All patients 364 26 7.1

DYSPEPS IA QUESTIONNAIRE VAL IDAT ION STUDY 483

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

The LDQ has previously demonstrated a sensitivity

of 80% (95% CI: 65–91%) and a specificity of 79%

(95% CI: 66–89%) in a primary care population.10

These values were marginally higher than the

SF-LDQs sensitivity of 77% (95% CI: 68–85%) and

specificity of 73% (95% CI: 68–78%) using the

summed total score. However, this difference is not

statistically significant, and even if the SF-LDQ was

slightly less valid than the LDQ, this would be offset

by the increased acceptability, feasibility and reliabil-

ity of the shorter self-completed measure.17 The SF-

LDQ had a high level of internal consistency when

tested by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and the item-

total correlation method, indicating that all of the

questions in the questionnaire scale were measuring

the same underlying construct, producing a high

level of reliability. The SF-LDQ had a higher score

for Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.90) than the LDQ

(0.69),10 suggesting that the shorter form was more

accurately measuring a single construct.

Assessment of concurrent validity involves compar-

ing the questionnaire against a ‘gold standard’. As

there is no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of dyspep-

sia6, 22, 23 a GPs’ diagnosis was chosen as a quasi-gold

standard. Validity has been established compared with

a clinician’s diagnosis in previous studies,10, 19, 24–27

whilst other studies of dyspepsia outcome measures

have used different ‘gold standard’ comparisons to

demonstrate concurrent validity, such as generic qual-

ity of life scores,28–33 patient self-assessment using

diaries34 and dyspepsia adverse events.35 An alternat-

ive approach would have been to compare the SF-LDQ

with the LDQ as the gold standard.17 However, the cor-

relation between the two questionnaires would have

been artificially inflated by the presence of four iden-

tical questions. No attempt was made to standardize

GPs’ diagnosis through discussion of the 1988 Work-

ing Party definition of dyspepsia with them.18 Stan-

dardizing the GPs’ diagnosis in this way would have

artificially increased the concurrent validity of the

SF-LDQ, because the questionnaire is based upon the

Working Party definitions.

It should be emphasized that the SF-LDQ is designed

as an outcome assessment tool and not as a diagnostic

tool. Although considerable effort has been made by

the Rome process to disentangle reflux and epigastric

pain, this has not been successful where patients have

not had endoscopic investigation to exclude peptic

ulcer and oesophagitis. Exclusion of patients with pre-

dominant reflux-like symptoms did not substantially

alter the concurrent validity of the SF-LDQ, when

assessed by the area under the ROC curve for the

summed frequency score. This suggests that using the

Rome II definition of dyspepsia instead of the 1988

Working Party definition has little influence on the

concurrent validity of the SF-LDQ. Both GERD and

dyspepsia have recently been re-defined by the Rome

III panel.36, 37 These changes are designed to aid fur-

ther research in selected subgroups of patients and do

not alter the nature of symptoms sought as outcome

measures for use in uninvestigated patients, where

both reflux symptoms and epigastric pain commonly

coexist.

The correlation between the test–retest SF-LDQ scores

2 days apart was 0.93, showing a high degree of reliab-

ility. Whilst only 40% of patients returned the second

questionnaire, this low response rate was not unex-

pected for a primary care sample where most partici-

pants do not have dyspepsia. The LDQ had a weaker

correlation between the two questionnaire scores (0.83)

when test–retest reliability was assessed,10 but the

response rate for the second questionnaire was higher

(96% in a secondary care population). Validation of the

SF-LDQ as a postal questionnaire was not carried out in

this study. However, the reliability, validity and respon-

siveness should not be affected by postal completion,

as it is a self-completed instrument. Interpretability and

acceptability of the SF-LDQ were demonstrated, sug-

gesting that the questionnaire should have a good

response rate. The response rate was only 40% in the

test–retest sample, but it was 78% in the responsiveness

to change sample (secondary care), where dyspepsia

was more salient to the respondents. The SF-LDQ’s

responsiveness to change was highly statistically signi-

ficant in 37 patients receiving a treatment of known

effectiveness. The standardized response mean values

suggested this response to change was large. The LDQ

was assessed in a similar way and was found to be

equally responsive to change, although the standard-

ized response mean was not calculated.10 Other studies

have used two groups receiving treatment and placebo,

in order to compare the responsiveness of the two

groups.38, 39 However, it is not ethical to use placebos

except in the context of a randomized-controlled trial,

so this was not possible in this study. There was no

alternative method of confirming that a response to

change had occurred in this study, such as a blinded

clinician assessment after treatment or a question on

self-reported global improvement, as the treatments

used have proven efficacy.40–42

484 A. FRASER et al.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Three percent of respondents commented that the

text size was too small and a larger version of the

questionnaire should be made available for such

patients in clinical trials. Non-English speaking

patients were excluded from this study, but should be

included in clinical dyspepsia trials to increase gener-

alizability. Translation of the SF-LDQ into other lan-

guages would alter its characteristics, necessitating

further validation.17, 31

The SF-LDQ is a self-completed outcome measure

that assesses both the frequency and severity of dys-

pepsia symptoms for which acceptability, interpretabil-

ity, reliability, validity and responsiveness to change

have been demonstrated. It is a precise measure using

the summed total score of frequency and severity

responses and has good feasibility due to its brevity.

The SF-LDQ meets all the criteria for an outcome

measure for dyspepsia in cost-effectiveness trials, and

is particularly well suited to primary care trials invol-

ving uninvestigated patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was undertaken by Dr Adam Fraser as part

of a Masters in Primary Care degree at the University

of Birmingham. John C. Duffy provided statistical

advice at the Department of Primary Care and General

Practice, University of Birmingham. He carried out the

sensitivity analyses and logistic regression analyses.

Val Redman and Beth Hinks are Research Associates at

the Department of Primary Care and General Practice,

University of Birmingham. They assisted with patient

recruitment and data entry.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Adam Fraser: Lead contributor to study design and

planning, conducting the study, data analysis and wri-

ting the manuscript; Brendan C. Delaney: guarantor of

the submission and corresponding author. Contributed

to study design and planning, and writing the manu-

script; Alexander C. Ford: responsible for conducting

the secondary care arm of the study at Leeds General

Infirmary; Michelle Qume: contributed to conducting

the study, data entry and analysis and writing the

manuscript; Paul Moayyedi: contributed significantly

to study design and planning, especially questionnaire

development. All authors have checked and approved

the final draft submitted.

STATEMENT OF INTERESTS

Authors’ declaration of personal interests: All authors

were employed by the University of Birmingham at

the time of this study.

Declaration of funding interests: The study was fun-

ded in full by the Medical Research Council as part of

the CUBE trial (ISRCTN 87644265). The general prac-

tices involved were reimbursed by the Midlands

Research Practices Consortium (MidReC) for each

patient enrolled. Gastroenterologists recruited patients

in secondary care without remuneration.

REFERENCES

1 Delaney BC, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al.

The management of dyspepsia: a sys-

tematic review. Health Technol Assess

2000; 4: 1–189.

2 Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management

guidelines for the millennium. Gut

2002; 50: 72iv–8.

3 Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Horwood SP.

Application of multi-attribute utility

theory to measure social preference for

health states. Oper Res 1982; 30:

1043–69.

4 Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, Williams A.

Variations in population health status:

results from a United Kingdom national

questionnaire survey. BMJ 1998; 316:

736–41.

5 Fraser A, Delaney B, Moayyedi P.

Symptom-based outcome measures for

dyspepsia and GERD trials: a systematic

review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:

442–52.

6 Agreus L. Natural history of dyspepsia.

Gut 2002; 50: 2iv–9.

7 Sharma N, Donnellan C, Preston C,

Delaney B, Duckett G, Moayyedi P. A

systematic review of symptomatic out-

comes used in oesophagitis drug ther-

apy trials. Gut 2004; 53 (Suppl. 4):

iv58–65.

8 Talley NJ. A critique of therapeutic tri-

als in Helicobacter pylori-positive func-

tional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 1994;

106: 1174–83.

9 McColl E. Best Practice in Symptom

Assessment: a review. Gut 2004; 53

(Suppl. 4): iv49–54.

10 Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D,

et al. The Leeds Dyspepsia Question-

naire: a valid tool for measuring the

presence and severity of dyspepsia. Ali-

ment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 1257–

62.

11 Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Ini-

tial validation of a diagnostic question-

naire for gastroesophageal reflux

disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:

52–7.

12 Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori Eradi-

cation in General Practice: Medical

DYSPEPS IA QUESTIONNAIRE VAL IDAT ION STUDY 485

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Benefits and Health Economics. Leeds:

Institute of Epidemiology and Health

Services Research, University of Leeds,

1999.

13 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. The

English Indices of Deprivation. London:

Neighbourhood Renewal Unit, 2004.

14 Heading RC. Prevalence of upper gastro-

intestinal symptoms in the general pop-

ulation: a systematic review. Scand

J Gastroenterol Suppl 1999; 231: 3–8.

15 Stanghellini V. Three-month prevalence

rates of gastrointestinal symptoms and

the influence of demographic factors:

results from the Domestic/International

Gastroenterology Surveillance Study

(DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl

1999; 231: 20–8.

16 Talley Colin-Jones NJD, Koch KL,

Koch M, Nyren O, Stanghellini V. Func-

tional dyspepsia: a classification with

guidelines for diagnosis and manage-

ment. Gastroenterol Int 1991; 4: 145–

60.

17 Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ,

Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based out-

come measures for use in clinical trials.

Health Technol Assess 1998; 2: 1–74.

18 Management of dyspepsia: report of a

working party. Lancet 1988; 1: 576–9.

19 Buckley MJ, Scanlon C, McGurgan P,

O’Morain CA. A validated dyspepsia

symptom score. Ital J Gastroenterol

Hepatol 1997; 29: 495–500.

20 Poitras MR, Verrier P, So C, Paquet S,

Bouin M, Poitras P. Group counseling

psychotherapy for patients with func-

tional gastrointestinal disorders: devel-

opment of new measures for symptom

severity and quality of life. Dig Dis Sci

2002; 47: 1297–307.

21 Calvet X, Bustamante E, Montserrat A,

et al. Validation of phone interview for

follow-up in clinical trials on dyspepsia:

evaluation of the Glasgow Dyspepsia

Severity Score and a Likert-scale symp-

toms test. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol

2000; 12: 949–53.

22 Dent J. Definitions of reflux disease and

its separation from dyspepsia. Gut 2002;

50: 17iv–20.

23 Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC,

Koch KL, Malagelada JR, Tytgat GN.

Functional gastroduodenal disorders.

Gut 1999; 45 (Suppl. 2): II37–42.

24 Greatorex R, Thorpe JA. Clinical assess-

ment of gastro-oesophageal reflux by

questionnaire. Br J Clin Pract 1983; 37:

133–5.

25 Junghard O, Lauritsen K, Talley NJ,

Wiklund IK. Validation of seven graded

diary cards for severity of dyspeptic

symptoms in patients with non-ulcer

dyspepsia. Eur J Surg Suppl 1998; 583:

106–11.

26 Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL,

Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire

for gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69: 539–47.

27 Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM,

Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ III. Assess-

ment of functional gastrointestinal dis-

ease: the bowel disease questionnaire.

Mayo Clin Proc 1990; 65: 1456–79.

28 Hu WH, Lam KF, Wong YH, et al. The

Hong Kong index of dyspepsia: a valid-

ated symptom severity questionnaire for

patients with dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2002; 17: 545–51.

29 Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B,

Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I.

Quality of life in patients with upper

gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved

evaluation of treatment regimens?

Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28: 681–7.

30 Shaw M, Talley NJ, Adlis S, Beebe T,

Tomshine P, Healey M. Development of

a digestive health status instrument:

tests of scaling assumptions, structure

and reliability in a primary care popula-

tion. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12:

1067–78.

31 Goldman J, Conrad DF, Ley C, et al.

Validation of Spanish language dyspep-

sia questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:

624–40.

32 Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Russell I, et al.

Developing a condition-specific measure

of health for patients with dyspepsia

and ulcer-related symptoms. J Clin Epi-

demiol 1996; 49: 565–71.

33 Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee

S, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life

Index: development, validation and

application of a new instrument. Br J

Surg 1995; 82: 216–22.

34 Leidy NK, Farup C, Rentz AM,

Ganoczy D, Koch KL. Patient-based

assessment in dyspepsia: development

and validation of Dyspepsia Symptom

Severity Index (DSSI). Dig Dis Sci

2000; 45: 1172–9.

35 Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Goldstein JL,

Eisen G, Dedhiya SD, Burke TA. Reliab-

ility, validity, and responsiveness of

severity of dyspepsia assessment (SODA)

in a randomized clinical trial of a COX-

2-specific inhibitor and traditional

NSAID therapy. Am J Gastroenterol

2002; 97: 32–9.

36 Drossman DA. The functional gastroin-

testinal disorders and the Rome III Pro-

cess. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:

1377–90.

37 Vakil N, VanZanten S, John D, Kahrilas

P, Roger J. The Definition of GERD: a

Global, Evidence-based Consensus.

Los Angeles, USA: Digestive Disease

Week, 2006.

38 Rabeneck L, Cook KF, Wristers K,

Souchek J, Menke T, Wray NP. SODA

(severity of dyspepsia assessment): a

new effective outcome measure for dys-

pepsia-related health. J Clin Epidemiol

2001; 54: 755–65.

39 Rothman M, Farup C, Stewart W,

Helbers L, Zeldis J. Symptoms associ-

ated with gastroesophageal reflux dis-

ease: development of a questionnaire

for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci

2001; 46: 1540–9.

40 Laine L, Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS. Has the

impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy

on ulcer recurrence in the United States

been overstated? A meta-analysis of

rigorously designed trials. Am J Gast-

roenterol 1998; 93: 1409–15.

41 Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM,

Hunt RH. Speed of healing and

symptom relief in grade II to IV gastr-

oesophageal reflux disease: a meta-ana-

lysis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:

1798–810.

42 Penston JG. Review article: Clinical

aspects of Helicobacter pylori eradica-

tion therapy in peptic ulcer disease. Ali-

ment Pharmacol Ther 1996; 10: 469–86.

ª 2007 The Authors, Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 477–486

Journal compilation ª 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

486 A. FRASER et al.