1996 Mc Glone CM Food for thought

Transcript of 1996 Mc Glone CM Food for thought

JOURNAL OF MEMORY AND LANGUAGE 35, 544–565 (1996)ARTICLE NO. 0029

Conceptual Metaphors and Figurative Language Interpretation:Food for Thought?

MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

Lafayette College

How do people interpret metaphors such as The lecture was a three-course meal? Lakoff(1993) has proposed that figurative expressions are interpreted as instantiations of deep conceptualmetaphors, such as IDEAS ARE FOOD. In contrast, Glucksberg (1991) has proposed thatmetaphors are interpreted as assertions of the topic’s (e.g., lecture) membership in an attributivecategory exemplified by the vehicle (e.g., three-course meal). Four experiments that test thepredictions of the two views are reported. The results suggest that reference to a conceptualmetaphor is not the modal strategy that people use when paraphrasing metaphors (Experiments1 and 2), rating the similarity between metaphors (Experiment 3), or retrieving metaphors frommemory (Experiment 4). In each of these situations, participants relied primarily on the stereotypi-cal properties of the vehicle concept. The results from these experiments are consistent withGlucksberg’s (1991) attributive categorization proposal. q 1996 Academic Press, Inc.

People use metaphors such as Our marriage way as literal comparisons, such as Nectarineswas a rollercoaster ride in everyday dis- are like oranges.course, and they are easily understood by their Although attractive in their simplicity, com-addressees. How is this understanding accom- parison models fail for the important case inplished? Some theorists have argued that met- which the addressee is not aware of the rele-aphors are interpreted as implicit comparison vant properties that the topic and vehicle con-statements, rather than categorical assertions. cepts share. Consider once more the claim OurFor example, Ortony (1979) and Gentner marriage was a rollercoaster ride. For people(1983; Wolff & Gentner, 1992) have proposed who are not familiar with the marriage inthat metaphors of the form X is a Y are inter- question, there can be no a priori representa-preted as comparisons of the form X is like a tion of the marriage that includes propertiesY. Once the implicit comparison is recognized, such as ‘‘exciting,’’ ‘‘scary,’’ or ‘‘unstable.’’these theorists argue, the addressee then con- Yet these are exactly the sorts of propertiesducts a search for matching properties in the that come to mind upon an uninformed read-topic (e.g., our marriage) and vehicle (e.g., ing of the statement.rollercoaster ride) concepts. The implication Comparison models are ill-equipped to dealof these ‘‘comparison models’’ is that meta-

with any metaphor that is used to make infor-phors are understood in essentially the same

mative assertions about a topic—i.e., to intro-duce properties that are not part of the address-ee’s mental representation of the topic. This

This research was supported by a Public Health Service argument applies with equal force to manygrant (HD25826) to Sam Glucksberg of Princeton Univer-

literal comparisons. For example, if a personsity. I thank Sam for his support during all stages of thisknows nothing about kumquats, then tellingresearch. Thanks also to Susan Fussell, Boaz Keysar, Phil

Johnson-Laird, Marcia Johnson, Deanna Manfredi, Lisa her that A kumquat is like an orange will intro-Torreano, and two anonymous reviewers for their com- duce new properties into her mental represen-ments on earlier versions of this paper. Address corre- tation of the concept ‘‘kumquat,’’ rather thanspondence and reprint requests to Matthew S. McGlone,

produce a match between ‘‘kumquat’’ andDepartment of Psychology, Lafayette College, Easton, PA18042. E-mail: [email protected]. ‘‘orange’’ properties.

5440749-596X/96 $18.00Copyright q 1996 by Academic Press, Inc.All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$21 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

545METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

Instead of property matching, informative Glucksberg (1991) has argued for the first sce-nario, proposing that metaphors, like many lit-literal comparisons require a property attribu-

tion strategy to be understood: the vehicle con- eral comparisons, are understood by castingthe topic and vehicle concepts in a commoncept provides candidate properties that may

plausibly be attributed to the topic. This attri- category. Lakoff (1993) has argued for thesecond scenario. According to his proposal,bution process is often based on an implicit

categorization of the vehicle. Upon hearing metaphors and other figurative expressions areunderstood via reference to metaphoric corre-the statement A kumquat is like an orange,

the addressee may infer that they are alike in spondences that structure the interpreter’s un-derstanding of abstract concepts. To under-that they are both citrus fruits. Once the ‘‘cit-

rus fruit’’ category is inferred, the addressee stand the implications of these two proposalsfor a general account of metaphor interpreta-may attribute properties of this category, such

as pulpy flesh, tangy taste, and high vitamin tions, let us consider each one in more detail.C content, to the unfamiliar concept ‘‘kum-

ATTRIBUTIVE CATEGORIZATION VIEWquat.’’Can this strategy be extended to metaphors? Glucksberg and his colleagues (Glucksberg,

1991; Glucksberg & Keysar, 1990; Glucks-Recall Our marriage was a rollercoaster ride.The topic and vehicle concepts may each be- berg & McGlone, in press) have argued that

metaphors are interpreted as what they appearlong to several categories. A marriage is a typeof relationship and, more generally, a type of to be: category-inclusion assertions of the

form X is a Y. According to this proposal,social contract. A rollercoaster ride is a typeof recreational activity and also a type of jour- interpreters infer from a metaphor a category

(a) to which the topic concept can plausiblyney. These concepts belong to other categoriesas well, but there does not appear to be a belong, and (b) that the vehicle concept exem-

plifies. For example, consider Their lawyer isconventional category that contains themboth. If there is no such category, what is a shark. Since the topic their lawyer cannot

plausibly belong to the taxonomic categorythe implied ground of the metaphor? Considertwo possibilities. One possibility is that the named by the vehicle shark (i.e., the actual

marine fish), this category is not ultimatelymetaphor implies a common category, but nota conventional, lexicalized category. For ex- considered as the basis for interpreting the ex-

pression; instead, the interpreter infers a cate-ample, a marriage and a rollercoaster ride canboth belong to a category of exciting and/or gory of things that the vehicle exemplifies

(e.g., vicious, cunning beings) and can includescary situations. A second possibility is thatthe metaphor does not imply a common cate- the topic among its members. When such a

category is used to characterize a metaphorgory, but rather a general correspondence be-tween two separate categories. For example, topic, it functions as an attributive category in

that it provides properties (viciousness, cun-the relationship between a marriage and a roll-ercoaster ride may be understood in terms of ning) that may be attributed to the topic. With

extensive use, the attributive category exem-metaphorical correspondences between loveand journeys, in which the lovers correspond plified by a vehicle concept may become con-

ventional. For example, many dictionaries in-to travellers, the relationship corresponds to amoving vehicle, the lovers’ excitement corre- clude the attributive category exemplified by

shark as a secondary meaning of the term.sponds to the speed of the vehicle, and soforth. In property attribution terms, the attributive

categorization view suggests two kinds ofEither of these possibilities would providethe interpreter with a way to attribute the prop- knowledge that interpreters should have to

make sense of a metaphor. First, one musterties of a rollercoaster ride to a marriage. Butwhich scenario describes what people actually know enough about the topic concept to ap-

preciate the attributive category to which itdo? This has been a matter of debate.

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

546 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

can plausibly and meaningfully belong. Sec- ‘‘journey.’’ For example, the conceptual met-aphor1 RELATIONSHIPS ARE CONTAIN-ond, one must be sufficiently familiar with the

vehicle concept to know the categories it can ERS2 entails a correspondence between thelove relationship and a container and betweenexemplify or epitomize. The most apt and

comprehensible metaphor vehicles are typical the lovers and entities inside a container.These correspondences are inferred from ex-members of the attributive categories to which

they are used to refer. Thus, a literal shark is pressions such as We are in love, We fell outof love, and We are trapped in this relation-a typical member of the category of ‘‘vicious,

cunning beings,’’ along with wolves and ship. The conceptual metaphor LOVE IS AJOURNEY entails correspondences betweensnakes. Conventional metaphor vehicles such

as shark, wolf, and snake can be understood lovers and travelers, the love relationship anda traveling vehicle, problems in the relation-immediately, given a relevant metaphor topic.

Understanding a novel metaphor such as Their ship and obstacles in the path of travel, andso forth. These correspondences are inferredlawyer is a vampire may take more time be-

cause one must infer the attributive category from figurative expressions such as We are ata crossroads in our relationship, Love is athat the vehicle exemplifies (e.g., ‘‘someone

who subsists by draining the resources of two-way street, We may have to go our sepa-rate ways, etc.others’’).

According to this view, a metaphor vehicle Gibbs (1992, 1994) has extended Lakoff’soriginal proposal to account for the productionmay elicit different interpretations depending

on the topic and other contextual constraints. and comprehension of novel metaphors in thesame system as idiomatic expressions. Ac-For example, the expression A lifetime is a

day may be interpreted in several ways, de- cording to Gibbs, novel metaphors rarely cre-ate attributive categories de novo, but ratherpending on the kind of thing a day is perceived

as symbolizing. A day can symbolize a rela- instantiate established conceptual metaphori-cal themes. For example, the metaphors Ourtively short time span, and so the expression

may be interpreted to mean that life is short. love is a voyage to the bottom of the sea andOur marriage was a rollercoaster ride bothAlternatively, a day may be perceived as sym-

bolic of a series of temporal stages, and thus employ topics and vehicles that are consistentwith the conceptual metaphor LOVE IS Athe expression may be interpreted as an asser-

tion of the correspondences between dawn and JOURNEY. By virtue of this common concep-tual core, Gibbs argues, the two metaphorsbirth, morning and youth, night and death, etc.convey ‘‘only slightly different entailments

CONCEPTUAL METAPHOR VIEW about love’’ (1992, p. 574).The systematic clustering of figurative ex-Rich interpretations of this latter sort have

been the focus of another theory of metaphor, pressions around conceptual metaphors likeLOVE IS A JOURNEY is striking. At thethat proposed by the linguist George Lakoff

and his colleagues (Lakoff, 1987, 1990, 1993; very least, this systematicity implies that manyof these expressions have a common meta-Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Lakoff & Turner,

1989; see also Gibbs, 1992, 1994). Accordingto their proposal, the production and compre-

1 The dual reference of the term ‘‘metaphor’’ in La-hension of figurative expressions are mediated koff’s writings is a potential source of confusion. Theby metaphorical correspondences that are part term is used to refer both to the verbal trope (its conven-

tional sense) and to the hypothesized system of correspon-of the human conceptual system. For example,dences between conceptual domains. Cognitive scientistsconsider the concept of love. According tohave traditionally used the term‘‘analogy’’ to convey thisLakoff, love is understood in terms oflatter sense. However, in fairness to conceptual metaphor

‘‘conceptual metaphors’’ that assimilate this theorists, I will follow their convention.abstract ‘‘target’’ concept into concrete 2 Following Lakoff’s convention, I will use uppercase

titles to identify conceptual metaphors.‘‘source’’ concepts, such as ‘‘container’’ and

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

547METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

phorical derivation (Sweetser, 1990). How- the topic and vehicle concepts may belong towhen interpreting a metaphor. For example,ever, the functional role of conceptual meta-

phors in idiom and metaphor interpretation re- Our marriage was a rollercoaster ride maybe interpreted as an assertion that the marriagemains unclear. Although conceptual metaphor

theorists have not articulated this role, there belongs to a category of situations that roll-ercoaster rides exemplify, such as situationsare at least three possibilities. One possibility

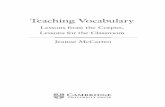

is that conceptual metaphors play no role in that are exciting and/or scary. Figure 1 pro-vides a schematic illustration of how the CMthe interpretation of figurative expressions. As

with most words, the comprehension of meta- and AC views differ in their accounts of howthis metaphor may be interpreted.phorical expressions may proceed without re-

course to or awareness of their etymological This portrayal of the two views suggests away to empirically distinguish them. Ac-origins. People may be able to appreciate the

underlying metaphor when it is pointed out to cording to the AC view, a metaphor vehiclecues the interpreter to think of categories ofthem, but it need not be explicitly represented

as conceptual knowledge. A second possibil- which the concept is emblematic or symbolic.To be relevant in context, this category mustity is that conceptual metaphors are available

in conceptual–semantic memory, and may be be one that can plausibly and meaningfullyinclude the metaphor topic. For Our marriageretrieved in certain situations. In this scenario,

conceptual metaphors are not necessary for was a rollercoaster ride, a relevant categorymight be the class of situations that are excit-immediate comprehension, but may be recog-

nized and appreciated in contexts that moti- ing and/or scary. Although rollercoaster ridemay cue other categories (e.g., amusementvate people to search for an underlying meta-

phorical theme (Nayak & Gibbs, 1990). A park rides, journeys), only those categoriesthat may include the topic our marriage arethird possibility is that conceptual metaphors

are both available and accessible in any con- deemed relevant to the metaphor.In contrast, the strong form of the CM viewtext, and thus may serve as the conceptual

basis for on-line figurative language compre- suggests that the literal categories of the topicand vehicle concepts play primary roles inhension. Lakoff (1993) appears to endorse this

last possibility when he suggests that the sys- metaphor interpretation. When an interpreterencounters Our marriage was a rollercoastertem of conceptual metaphors ‘‘. . . is used

constantly and automatically, with neither ef- ride in discourse, how does she determinewhich conceptual metaphor is relevant? Thefort nor awareness’’ (pp. 227–228). The cur-

rent study focuses on this strong form of the only cues available for selecting the appro-priate metaphor are the topic and vehicleconceptual metaphor view.themselves. The interpreter must recognize

COMPARING THE TWO VIEWS the membership of marriage and rollercoasterrides in the categories of ‘‘love relationships’’The most salient difference between the

conceptual metaphor and attributive categori- and ‘‘journeys’’ to apply the LOVE IS AJOURNEY correspondences to this expres-zation views (hereafter, the CM and AC

views) is the knowledge base that is presumed sion. If the appropriate superordinate catego-ries are not recognized, then a CM-interpreta-to underlie the metaphor interpretation pro-

cess. According to the CM view, the primary tion is not possible.At present, the evidence available to sup-knowledge base for interpretation is a rich set

of metaphorical correspondences between ab- port either the AC or CM accounts of meta-phor interpretation is indirect. Glucksbergstract and concrete domains (e.g., love–jour-

ney correspondences). The AC view, in con- (1991) has discussed several discourse phe-nomena associated with metaphors that sup-trast, posits no such metaphorical structures.

The AC view presumes that people rely upon port the AC account. For example, the fact thatmetaphors either change meaning or becometheir knowledge of the multiple categories that

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

548 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

FIG. 1. Two views of metaphor interpretation.

nonsensical when reversed (e.g., A roll- ate a common conceptual metaphor. Peopleoften speak of love in terms of journeys, angerercoaster ride was our marriage) is similar

to that which occurs when literal category- in terms of heat and pressure (e.g., blow yourstack, let off steam), ideas in terms of foodinclusion assertions are reversed (e.g., A bird

is a sparrow). Metaphor asymmetry and other (e.g., food for thought), and so on (Lakoff &Johnson, 1980). Although the linguistic evi-discourse phenomena, although consistent

with the argument, do not force the conclusion dence is consistent with the CM view, onemust avoid using this evidence in a circularthat metaphors are processed initially as cate-

gory-inclusion assertions. It is possible that manner. For example, the fact that people talkabout ideas in terms of food cannot be usedinterpreters treat metaphors as such only in

later stages of processing, or perhaps only in to show both that people conceptualize ideasin terms of food and that people use this con-certain interpretational contexts. The available

evidence cannot distinguish among these pos- ceptualization to understand food-oriented ex-pressions about ideas. The conceptual statussibilities.

The primary evidence for the CM view is of a metaphor such as IDEAS ARE FOODmust be established independently of the lin-the observed systematicity of idiomatic ex-

pressions in certain semantic domains. Many guistic evidence.At present, there is no conclusive evidenceof the conventional expressions used to de-

scribe abstract concepts do appear to instanti- to support the claim that conceptual metaphors

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

549METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

are accessed to interpret metaphorical lan- pressions such as We are trapped in this rela-tionship (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). If, asguage. Furthermore, the studies that have ad-

dressed this issue have focused exclusively on Gibbs (1992) has argued, interpretation of thisexpression requires mental reference to a con-idiomatic expressions, although Gibbs (1992)

has claimed that metaphors are understood via ceptual metaphor, then one might expect para-phrases that reflect the correspondences be-the same conceptual structures as idioms. Ba-

sic questions about the role of conceptual met- tween the source and target domains. In thiscase, one might expect to observe people ei-aphors in metaphor interpretation remain

unanswered: Do the products of metaphor in- ther pointing out the correspondences (e.g.,‘‘their relationship is like a filing cabinet interpretation reflect conceptual correspon-

dences between the topic and vehicle do- that it contains their hopes and dreams’’) orby using terms from the source domain (e.g.,mains? Are these correspondences encoded in

memory when a metaphor is understood? ‘‘they are trapped/confined in the relation-ship’’). If, on the other hand, interpreters rec-Glucksberg’s attributive categorization pro-

posal raises similar questions: Does the ognize or infer an attributive category exem-plified by the metaphor vehicle, then oneground of a metaphor reflect an attributive cat-

egory? Is this attributive category encoded in might expect paraphrases that focus on theproperties of this category. For example, a fil-memory?

The experiments reported here were de- ing cabinet is a prototypical member of cate-gories such as ‘‘organized things’’ and ‘‘busi-signed to address these questions. In Experi-

ments 1 and 2, people’s written interpretations ness-oriented things.’’ If these categoriescome to mind when the metaphor is encoun-(i.e., paraphrases) were analyzed to determine

whether people refer to CM correspondences tered, interpreters should attribute propertiessuch as ‘‘organized’’ or ‘‘business-oriented’’or categorical attributes when explaining a

metaphor’s meaning. Experiment 3 investi- to the relationship.Previous studies that have directly exam-gated whether people perceive the similarity

between metaphors in terms of CM correspon- ined people’s paraphrases of metaphors (Gen-tner & Clement, 1988; Glucksberg & Man-dences or attributive category membership.

Finally, a cued recall paradigm was used in fredi, 1995; Ortony, Vondruska, Foss, &Jones, 1985; Tourangeau & Rips, 1991) haveExperiment 4 to determine the nature of the

representation that is encoded when a meta- generally found that people describe a meta-phor’s meaning in terms of individual proper-phor is understood.ties, rather than conceptual correspondences

EXPERIMENT 1: PARAPHRASING METAPHORS between the topic and vehicle. For example,Gentner and Clement (1988) found that peo-Perhaps the most straightforward way to in-

vestigate the knowledge sources that people ple’s interpretations of similes (e.g., Ciga-rettes are like time bombs) tended to includeuse to interpret metaphors is to examine the

ways people articulate a metaphor’s meaning. properties exemplified by the vehicle concepts(e.g., ‘‘do their damage after some period ofTo the extent that one can specify the differ-

ence between a paraphrase based on CM cor- time during which no damage is evident’’).These are exactly the type of properties onerespondences and one based on an attributive

category, an analysis of people’s paraphrases would expect participants to mention if theyrecognized the attributive category exempli-may differentiate between the two accounts.

For example, consider the novel metaphor Our fied by the vehicle. The authors do not reportany paraphrases that could be construed asrelationship is a filing cabinet. The choice of

topic and vehicle terms make this metaphor a referring to a conceptual metaphor. However,the figurative expressions used in this andgood candidate for instantiating the concep-

tual metaphor RELATIONSHIPS ARE CON- other previous studies did not involve topicand vehicle concepts from the source and tar-TAINERS, which presumably underlies ex-

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

550 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

get domains discussed by CM theorists. Per- words. At no point in the procedure did theexperimenter mention the potential CM under-haps metaphors drawn from these domains

have a special conceptual status and thus are pinnings of the expressions. Participants com-pleted their questionnaires while seated at aunderstood differently from other figurative

expressions. table in a private room. On average, partici-pants took 40 min to complete their ratingsThe logic of Experiment 1 was straightfor-

ward. Participants were asked to paraphrase a and paraphrases.Content analysis. Two additional partici-variety of metaphors instantiating conceptual

metaphors that CM theorists have described. pants served as coders for this analysis. Afterreceiving an informal tutorial on the notionThese paraphrases were then coded by judges

to determine the frequency with which refer- of conceptual metaphors and their relation tofigurative language, the coders received a 32-ences to an underlying conceptual metaphor

were made. page packet of materials. This packet con-tained a typed transcript of the 480 generated

Method paraphrases (16 metaphors 1 30 participants),the stimulus metaphors, and their accompa-Participants. Thirty-two Princeton under-

graduates, all native English speakers, were nying conceptual metaphors. At the top ofeach 2-page section (a separate section forpaid for their participation in this experiment.

Thirty of the participants generated para- each stimulus metaphor), the stimulus meta-phor appeared in boldface letters to the right,phrases and rated the comprehensibility of the

metaphor stimuli. Two additional participants and the corresponding conceptual metaphorappeared in uppercase letters to the left. Thecoded the paraphrase protocols.

Materials. Sixteen metaphorical sentences 30 generated paraphrases followed, numberedand double-spaced.were constructed for this experiment. These

sentences were created by choosing topic and The coders were instructed to rate eachparaphrase on a three-point scale (0 to 2) usingvehicle concepts from source and target do-

mains with potential CM correspondences of the following guidelines: A ‘‘0’’ rating indi-cated that the paraphrase did not containthe sort described by Lakoff and his col-words or phrases referring to the CM sourceleagues (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Lakoff &domain; a rating of ‘‘1’’ indicated that theTurner, 1989). Twelve of these sentences wereparaphrase contained words or phrases thatnominative, X is a Y metaphors (e.g., Our rela-might be construed as references to the sourcetionship is a filing cabinet, instantiating RE-domain, but the references were ambiguous;LATIONSHIPS ARE CONTAINERS). Thea rating of ‘‘2’’ indicated that the paraphrasesother four sentences were predicative meta-contained words or phrases that the coder feltphors in which an entire verb phrase is usedwere clearly references to the source domain.metaphorically (e.g., Tina planted the seeds

The coders made their ratings indepen-of discontent among the members of her officedently of one another and, upon first compari-pool, instantiating IDEAS ARE PLANTS).son, had an 87% agreement rate. Discrepanc-These sentences, along with their correspond-ies were resolved through discussion by theing conceptual metaphors, are presented incoders and, when necessary, by the input ofAppendix A.a third party. To illustrate how the coders usedProcedure. The metaphor stimuli were pre-the 0–2 scale, consider the following para-sented to participants in a three page question-phrases generated for the metaphor Dr. Mo-naire. The participants were instructed to readreland’s lecture was a three-course meal foreach sentence carefully and to rate its compre-the mind:hensibility on a scale of 1 (difficult to under-

stand) to 4 (easy to understand). After making (1) Dr. M’s [lecture] touched on a varietya rating, participants were asked to write a of topics, but was well-integrated, thorough

and intellectually stimulating.paraphrase of the metaphor in their own

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$22 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

551METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

(2) The lecture had a lot of information for Of the paraphrases generated in this experi-ment, fewer than 1/4 (24%) could be con-the mind to absorb.

(3) The lecture satisfied the mind’s intel- strued as containing references to an underly-ing conceptual metaphor. Since most partici-lectual hunger thoroughly.pants did not interpret the expressions in CM

This metaphor was created to instantiate the terms, what knowledge sources did they useconceptual metaphor IDEAS ARE FOOD to interpret the expressions? Consider the(Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The ratings that paraphrases participants generated for Oureach of the paraphrases above received reflect marriage was a rollercoaster ride (seetheir differential reliance on the use of food- Appendix B1). This metaphor was apparentlyoriented language to explain the metaphor’s understood in much the same way by all parti-meaning. Paraphrase (1) received a rating of cipants. They took it as a comment on the‘‘0’’, indicating that the coders did not per- emotional instability of the relationship: ‘‘ex-ceive any reference to the food domain in its citing,’’ ‘‘frenetic,’’ ‘‘stomach-churning,’’content. Paraphrase (3) received a rating of ‘‘there were good days and bad days,’’ etc.‘‘2’’, indicating that it did involve reference Some of the paraphrases contained referencesto the food domain (e.g., use of the word hun- that could be construed as relying on a meta-ger). Paraphrase (2) contained references that phoric correspondence between spatial orien-were ambiguous with respect to whether they tation and emotional valence (e.g., UP ISwere food-oriented (‘‘absorb’’ may or may GOOD and DOWN IS BAD, Lakoff, 1993).not be a reference to digestion), and thus re- None of the paraphrases, however, reflect theceived a rating of ‘‘1’’. LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor, nor do they

refer to journey-related properties. CompareResults and Discussion these paraphrases with those obtained for Our

love is a voyage to the bottom of the sea (seeThe mean comprehensibility ratings for the16 metaphors was 3.3 (SD Å 0.4), indicating Appendix B2). Despite a very clear allusion

to the LOVE IS A JOURNEY metaphor, therethat participants generally found the sentenceseasy to understand. No significant correlations was little consensus among participants about

the meaning of this expression. Some took itwere found between these ratings and para-phrase content variables, so these ratings will to mean that the relationship was exotic and

mysterious, others took it to mean that thenot be discussed further. The results of thecontent analysis were clear-cut. The vast ma- relationship was dangerous emotionally, and

still others took it as an assertion that the lov-jority of paraphrases, 76%, received a ratingof ‘‘0’’, indicating an absence of CM refer- ers do not communicate well (e.g., ‘‘We don’t

communicate; we’re as quiet as the bottom ofences. Fourteen percent received a rating of‘‘1’’ (ambiguous), and 10% received a rating the sea.’’). Some of the paraphrases do contain

journey-related references (e.g., journey, un-of ‘‘2’’ (transparent CM references). The fre-quencies for the ambiguous and transparent charted), but such references were infrequent

(only 2 of 30 paraphrases).CM paraphrases were combined (24%) to pro-duce a measure of the frequency of ‘‘poten- According to Gibbs (1992), both the roll-

ercoaster ride and voyage expressions are in-tial’’ CM references. Further analyses sug-gested that these overall frequencies reflected stantiations of the LOVE IS A JOURNEY

conceptual metaphor and therefore shouldthe response pattern of individual participants.For each of the 16 metaphors, there was a convey ‘‘only slightly different entailments

about love’’ (p. 574). Contrary to this asser-greater frequency of non-CM than CM para-phrases (sign test, p õ .001). Similarly, all tion, there was little interpretational overlap

in the paraphrases participants generated for30 participants produced non-CM paraphraseswith greater frequency than CM paraphrases the two expressions. Furthermore, it is diffi-

cult to explain the variability in the interpreta-(sign test, p õ. 001).

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$23 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

552 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

tions of the voyage expression if one assumes One way to deal with this potential problemis to specifically ask participants to providethat participants relied solely on LOVE IS A

JOURNEY correspondences. The AC view figurative paraphrases of the metaphors—thatis, to come up with other metaphors that ex-offers an alternative explanation. If, as

Glucksberg (1991) argues, the vehicle is un- press roughly the same idea. If this is a reason-able instruction, then participants should gen-derstood to name an attributive category, then

the comprehensibility of the metaphor should erate new metaphors that share a commonconceptual basis with the stimulus expression.be particularly sensitive to the typicality of

the vehicle in this category. Since most people According to the CM view, this conceptualbasis should be the underlying CM structureassociate an actual rollercoaster ride with

thrills and excitement, the concept can be used of the stimulus metaphor. Consequently, parti-cipants should generate metaphors that pre-as a label for the class of exciting, possibly

scary situations. A voyage to the bottom of serve the CM correspondences of the stimulusmetaphor. If, on the other hand, people under-the sea, however, does not invoke a strong

association: such a voyage may be a danger- stand a metaphor by drawing on their knowl-edge of the categories that the vehicle mayous, mysterious, or silent situation, but it does

not exemplify any of these situations in partic- exemplify, then one would expect people togenerate similar metaphors by choosing vehi-ular. The lack of a salient attributive category

leaves the metaphorical sense of voyage to cles from the same attributive category as thestimulus expression. These predictions werethe bottom of the sea open to interpretative

license. tested in Experiment 2.Although the AC view provides a plausible

explanation for the paraphrase results, the in- Methodfrequent occurrence of CM interpretations

Participants. Thirty-two Princeton under-does not rule out the possibility that partici-graduates were paid for their participation inpants were relying on conceptual metaphorsthis experiment. All of the participants wereto interpret the expressions. Since participantsnative English speakers. Thirty participated inwere given the simple instructions to ‘‘writethe metaphor generation task. Two additionalout a paraphrase in your own words,’’ theyparticipants coded the generation protocols.may have focused on vehicle properties cen-

Materials. The 16 metaphorical sentencestral to the metaphors’ meanings, as opposedcreated for Experiment 1 were used in thisto the conceptual knowledge underlying theirexperiment.interpretations. Furthermore, many partici-

Procedure. The stimulus metaphors werepants may also have construed the request forpresented to participants in a three-page ques-‘‘paraphrases’’ as an instruction to excludetionnaire. Each participant saw all 16 meta-any references of a figurative nature. Conse-phors. Participants were instructed to readquently, these participants may have made aeach metaphor carefully and then to rate itsconscious effort to avoid CM references incomprehensibility on a scale of 1 (difficult totheir interpretations. Experiment 2 addressesunderstand) to 4 (easy to understand). Afterthis potential problem.making the rating, participants were instructed

EXPERIMENT 2: PARAPHRASING METAPHORS to think of another metaphor that had the sameWITH METAPHORS or a very similar meaning and to write this

metaphor in the space provided below theOne possible explanation for the low inci-stimulus metaphor. At no point in the proce-dence of CM paraphrases in Experiment 1 isdure did the experimenter mention the poten-that participants understood the request fortial CM underpinnings of the expressions. Par-paraphrases as an instruction to describe theticipants completed their questionnaires whilemetaphor’s meaning in literal terms, while ex-

cluding any references of a figurative nature. seated at a table in a private room. On average,

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$23 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

553METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

participants took 45 mins to complete the cating that participants found them easy toquestionnaire. understand. No reliable correlations were

Content analysis. Two additional partici- found between these ratings and the para-pants served as coders in this analysis. The phrase content variables, so these ratings willprocedure for this analysis was similar to that not be discussed further. As in Experiment 1,in Experiment 1. After receiving an informal a majority of the paraphrases (59%) received atutorial on the notion of conceptual metaphors rating of ‘‘0’’, indicating that the paraphrasesand their relation to figurative language, each were inconsistent with the conceptual meta-coder received a packet of materials con- phors presumably underlying the stimulus ex-taining the stimulus metaphors, their accom- pressions. Nine percent received a rating ofpanying conceptual metaphors, and a typed ‘‘1’’ (ambiguous), and 32% received a ratingtranscript of the metaphors generated by parti- of ‘‘2’’ (CM-consistent). The frequencies forcipants. The coders were instructed to rate the ambiguous and CM-consistent para-each paraphrase on the same three-point scale phrases were combined (41%) to produce aused in the previous experiment. Upon first measure of the frequency of potentially CM-comparison, the coders had a 93% agreement consistent responses. Further analyses indi-rate. Disagreements were resolved through cated that the overall frequencies reflected thediscussion by the two coders and, when neces- response pattern of individual participants.sary, by the input of a third party. To illustrate For 13 of the 16 metaphors, there was a greaterhow the coders used the 0–2 scale in this frequency of CM-inconsistent than CM-con-experiment, consider the following para- sistent paraphrases (sign test põ .02). In addi-phrases generated in response to the stimulus tion, 22 of the 30 participants generated CM-metaphor Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a three- inconsistent paraphrases with greater fre-course meal for the mind: quency than CM-consistent paraphrases (sign

(1) Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a goldmine test p õ .05).for the mind. The percentage of CM-consistent para-

(2) Dr. M’s lecture was a truckload for the phrases increased substantially from Experi-mind. ment 1 to Experiment 2. This suggests that

(3) Dr. Moreland’s lecture was bread for the request for paraphrases (as opposed tomy starving mind. ‘‘metaphorical paraphrases) in Experiment 1The ratings each of these paraphrases received may have been understood by some partici-reflect their differential reliance on the CM pants as an instruction to exclude references ofsource domain, ‘‘food,’’ in generating new a figurative nature. Consequently, the resultsmetaphors. Paraphrase (1) received a rating of from Experiment 1 may underestimate the fre-‘‘0’’, indicating that the coders did not per- quency with which people resort to CM corre-ceive any reference to the food domain in its spondences when explaining a metaphor’scontent. Paraphrase (3) received a rating of meaning. It may also be the case, however,‘‘2’’, indicating that it did involve reference that the request for ‘‘metaphorical para-to the food domain (i.e., likening the lecture phrases’’ in the current experiment may haveto bread). Paraphrase (2) contained a reference created a spuriously high rate of CM-consis-that was ambiguous with respect to whether tent responses. For example, the presentationit was food-oriented (i.e., it was not clear to of an expression such as Our marriage was athe coders whether the ‘‘truckload’’ was com- rollercoaster ride may have produced literalprised of food or some other substance) and priming of journey-oriented terms indepen-thus received a rating of ‘‘1’’. dently of the hypothesized conceptual corre-Results and Discussion spondences underlying the expression. As a

result, participants who did not contemplateThe mean comprehensibility rating for thestimulus metaphors was 3.0 (SD Å 0.5), indi- these correspondences may nevertheless have

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$23 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

554 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

produced new metaphors employing vehicles cally—that is, by producing a new metaphorwith a similar meaning. Interestingly, the ma-from the journey domain.

Although the percentage of CM-consistent jority (59%) of these paraphrases were CM-inconsistent. One interpretation of this findingparaphrases increased from Experiment 1,

participants in the current experiment modally is that the CM-inconsistent paraphrases reflecta process of metaphor interpretation thatproduced CM-inconsistent paraphrases. What

aspects of the stimulus metaphors did these draws on a different knowledge base than thatCM-inconsistent paraphrases preserve? A sur- suggested by the CM view. This differentvey of the paraphrases generated suggests that knowledge base (e.g., attributive categories)most participants produced new metaphors enabled participants to see similarities be-that preserved the stereotypical properties of tween metaphors that would go unnoticed ifthe original vehicle concept, rather than the the metaphors were interpreted strictly insource domain of the underlying conceptual terms of CM correspondences. It could be ar-metaphor. Consider the metaphors partici- gued, however, that the ‘‘metaphorical para-pants generated to paraphrase Dr. Moreland’s phrase’’ task encouraged participants to em-lecture was a three-course meal for the mind ploy an interpretation strategy that is not rep-(see Appendix C1). This expression was de- resentative of the way they normally interpretsigned to instantiate the conceptual metaphor metaphors. For example, some participantsIDEAS ARE FOOD (Lakoff & Johnson, may have approached the task of generating1980), which involves a correspondence be- metaphors as a test of creative ability. As atween ideas and food, thinking and eating, un- result, they may have felt pressure to employderstanding and digestion, and so forth. Only an unconventional interpretation strategy to10 of the 30 paraphrases employed vehicles come up with novel metaphors. This wouldfrom the CM source domain of ‘‘food’’ (e.g., certainly be a problem if participants tried tobuffet). However, all of the new metaphors be creative by producing new metaphors thatproduced by participants reflect at least a par- were relatively dissimilar to the stimulus ex-tial recognition of the stereotypical properties pressions.of three-course meals that can be attributed to Experiment 3 was conducted to address thislectures, such as ‘‘large quantity’’ and ‘‘vari- concern and to further investigate the similari-ety.’’ The new vehicles may be grouped on ties people perceive among different meta-the basis of these shared properties. Most of phors. Participants were presented with a sam-the new vehicles retained the ‘‘large quantity’’ ple of the CM-consistent and CM-inconsistentproperty (e.g., flood, full tank of gas, truck- metaphors generated in Experiment 2 andload), while some also shared the ‘‘variety’’ were asked to rate the extent to which theseproperty (e.g., smorgasbord, Olympiad, trip metaphors were similar in meaning to thearound the world). The diversity of these vehi- original stimulus metaphors. Unlike the meta-cles suggests that participants understood phor generation task, a similarity ratings taskthree-course meal as something more than produces data that are not constrained by par-simply an exemplar from the food domain. ticipants’ language production abilities. In ad-Participants apparently recognized this con- dition, the task of making similarity ratings iscept as an exemplar of a category that may less likely to be construed by participants asalso include feasts, floods, and full tanks of a test of intelligence or creative ability.gas as members. Parallel results were obtained According to the CM view, people’s intu-with the other stimulus metaphors presented itions about the similarity between metaphors(see Appendix C2 for another example). should be based on the underlying conceptualEXPERIMENT 3: METAPHOR SIMILARITY AND structure of the expressions (Lakoff, 1993;

CM-CONSISTENCY Gibbs, 1992). For example, a metaphor suchas Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a three-courseIn Experiment 2, it was found that people

are able to paraphrase a metaphor metaphori- meal for the mind, which has the implicit con-

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$23 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

555METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

ceptual structure of IDEAS ARE FOOD, in this study. A third type of alternative, the‘‘unrelated’’ metaphors, was created for thisshould be rated as more similar in meaning to

other metaphors that share this structure (e.g., study. These were anomalous metaphors thatwere designed to be neither CM-consistent norDr. Moreland’s lecture was a steak for the

mind) than those that do not (e.g., Dr. Mo- attributively similar to the target (e.g., Dr. Mo-reland’s lecture was a ceiling fan for thereland’s lecture was a full tank of gas for the

mind). mind). The unrelated metaphors (three foreach target) were included as judgment an-According to the AC view, people should

perceive the similarity between metaphors in chors for the similarity scale and were ex-pected to elicit relatively low similarity rat-terms of the attributive categories that their

vehicles exemplify. If the vehicles exemplify ings. A seven-point similarity scale was pre-sented below each of the alternativethe same attributive category, the expressions

should be rated as similar in meaning. Thus, if metaphors. The ‘‘1’’ on this scale was labeled‘‘not at all similar’’ and the ‘‘7’’ was labeledpeople can conceive of an attributive category

exemplified by three-course meals that steaks ‘‘very similar.’’The three types of alternative metaphorsand full tanks of gas may also exemplify (e.g.,

‘‘things that come in large quantities’’), the were presented in a random order followingeach target. To control for possible order andsteak and full tank of gas expressions should

be rated as equally similar to the three-course position effects, two separate booklets (A andB) were constructed that presented each set ofmeal expression.alternatives in a different random order.

Method In designing the materials for the similarityratings task, there was some concern aboutParticipants. Thirty Lafayette College un-

dergraduates, all native English speakers, re- whether participants would view the CM-con-sistent and CM-inconsistent metaphors asceived course credit for their participation in

this experiment. equally apt. Specifically, if participants con-sidered the CM-consistent metaphors as lessMaterials. For the similarity ratings task,

booklets were constructed consisting of 16 apt than the CM-inconsistent metaphors, thedifference in aptness might override any effectsets of 10 metaphorical sentences. The first

sentences of each set, the ‘‘target’’ metaphors, of CM-consistency on the similarity ratings.To investigate this possibility, a group of 16were the stimulus metaphors used in Experi-

ments 1 and 2. The target metaphor was under- Lafayette undergraduates were recruited torate the aptness of the two metaphor types.lined and centered at the top of each page of

the booklet (e.g., Dr. Moreland’s lecture was The participants rated each metaphor’s apt-ness on a seven-point scale (with ‘‘1’’ labeleda three-course meal for the mind). The 9 sen-

tences that followed, the ‘‘alternative’’ meta- ‘‘not at all apt’’ and ‘‘7’’ labeled ‘‘very apt’’).The CM-inconsistent metaphors were rated asphors, were of three types. The ‘‘CM-consis-

tent’’ alternatives were metaphors generated slightly less apt than the CM-consistent meta-phors (4.18 and 4.36, respectively), althoughby participants in Experiment 2 that drew

from the same CM source domain as the target this difference was not reliable (t’s for theitem and subject analyses were less than 1).metaphor (e.g., Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a

smorgasbord for the mind). The ‘‘CM-incon- Thus, the results of this control study suggestthat there was no ‘‘aptness advantage’’ for thesistent’’ alternatives were metaphors gener-

ated in Experiment 2 that did not draw from inconsistent metaphors.Design and procedure. The experiment em-this source domain (e.g., Dr. Moreland’s lec-

ture was a full tank of gas for the mind). For ployed a 2 1 3 mixed design with one be-tween-subject factor (Booklet A or B) and oneeach target metaphor, three CM-consistent

and three CM-inconsistent alternatives were within-subject factor (Alternative Type).Upon arrival in the laboratory, participantschosen from the Experiment 2 corpus for use

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$24 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

556 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

were randomly assigned to Booklet A or B. lecture was a three-course meal for the min-d(target) than Dr. Moreland’s lecture was aThe experimenter instructed participants to

read through the entire set of materials and full tank of gas for the mind (CM-inconsis-tent). The AC view proposes that people un-then rate the similarity of the alternatives to

the target in each metaphor set. On average, derstand three-course meal as the name of acategory of ‘‘things that come in large quanti-participants took approximately 45 min to

complete their booklets. ties,’’ and thus other vehicles that belong tothis category, such as steak and full tank of

Results and Discussion gas, should be judged as similar in meaning.The current results are consistent with thisInitial analyses did not reveal a main effect

or interaction for the between-subjects factor view.Taken as a whole, the results from Experi-(Booklet), so further analyses were conducted

collapsing across this variable. The mean sim- ments 1–3 demonstrate that people do notmodally adopt a CM strategy to explain a met-ilarity ratings for the three alternative types

were as follows (higher ratings indicate higher aphor’s meaning. However, the reflective, de-liberate nature of paraphrase and ratings tasksdegrees of similarity to the target): 4.98 for the

CM -consistent, 4.75 for the CM-inconsistent, may not be generalizable to situations inwhich a metaphor is encountered in ongoingand 2.28 for the Unrelated.

The ratings data were analyzed using one- text or discourse. The knowledge base thatpeople use to reflectively interpret and ap-way repeated measures analyses of variance

(ANOVA) with Alternative Type as a within- preciate metaphors may be broader than thatwhich is required for immediate comprehen-subjects factor. Two such ANOVAs were con-

ducted, one treating subjects as a random fac- sion (Gerrig & Healy, 1983). For example, itis possible that people initially interpret meta-tor (Fs) and one treating items as a random

factor (Fi). A significant effect of Alternative phors in CM terms and only upon reflectionconsider the unique attributes of the vehicleType was found in both the subjects (Fs(2,58)

Å 384.06, p õ .01) and the items (Fi(2,30) Å concept. In Experiment 4, a cued-recall para-digm is used to investigate the nature of the208.51, p õ .01) analyses. Planned compari-

sons between the individual means revealed representation that is constructed when a met-aphor is understood in a time-constrained situ-that the unrelated metaphors were rated as less

similar to the target than either the CM -con- ation.sistent (ts(58)Å 22.06, põ .01; ti(30)Å 18.10,

EXPERIMENT 4: METAPHOR RECALLp õ .01) or the CM-inconsistent metaphors(ts(58) Å 21.25, p õ .01; ti(30) Å 15.27, p õ The manner in which people recall verbal

material is frequently used to demonstrate the.01). There was, however, no difference inthe similarity ratings obtained for the CM- constructive, elaborative nature of language

comprehension. Several studies have shownconsistent and CM-inconsistent metaphors(ts(58) Å 1.37, pú .05; ti(30) Å .91, pú .05). that the accessibility of verbal material to re-

call can provide a sensitive measure of howThe results of this experiment complementthose from Experiment 2 in demonstrating that the material was interpreted (e.g., Barclay,

Bransford, Franks, McCarrell, & Nitsch,people may perceive similarities among meta-phors that cannot be explained in terms of CM 1974; Blumenthal & Boakes, 1967; Tulving &

Thomson, 1973; Verbrugge & McCarrell,correspondences. Alternative metaphors thatwere CM-consistent with the target metaphors 1977). An important principle that has

emerged from these studies is that the opera-did not receive higher similarity ratings thanalternatives that were inconsistent. For exam- tions people use to encode and recall verbal

material are strongly interdependent. Tulvingple, Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a steak forthe mind (CM-consistent) was not perceived and Thomson (1973) coined the term ‘‘encod-

ing specificity’’ to refer to this principle.as more similar in meaning to Dr. Moreland’s

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$24 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

557METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

‘‘What is stored is determined by what is per- lectures as members. The ‘‘food’’ category isrejected in favor of a category that can includeceived and how it is encoded, and what is

stored determines what retrieval cues are ef- lectures as members, such as ‘‘things thatcome in large quantities.’’ This proposal sug-fective in providing access to what is stored’’

(Tulving & Thomson, 1973, p. 353). gests that an appropriate cue for recalling themetaphor is one that refers to a relevant attrib-The encoding specificity principle suggests

that recall will be most successful when there utive category (e.g., large quantity).In Experiment 4, a cued recall paradigmis strong match between the representation

that is generated during comprehension and was used to investigate the effectiveness of‘‘conceptual’’ and ‘‘attributive’’ cues inthe cues present at the time of recall. The CM

and AC views offer very different accounts as prompting metaphor recall. Pairs of sentenceswere constructed that provided a metaphoricalto the makeup of the representation that is

generated during metaphor comprehension. or a literal context for a vehicle concept suchas three-course meal. Cues that referred toAccording to the CM view, the representation

is composed of the conceptual correspon- either the CM source domain or attributivecategory of the vehicle were constructed. Fordences that are activated to understand the ex-

pression. For example, understanding The lec- example, the CM cue for three course mealwas food, and the AC cue was large quantity.ture was a three-course meal involves recog-

nizing the expression as an instantiation of If three-course meals’ status in the source do-main of ‘‘food’’ is central to the comprehen-the conceptual metaphor IDEAS ARE FOOD.

Since ideas are metaphorically linked to a va- sion of the expression, then food should be aneffective cue for recalling a metaphorical useriety of source domains (IDEAS ARE FOOD,

IDEAS ARE PLANTS, IDEAS ARE CUT- of the concept (The lecture was a three-coursemeal). In principle, the CM cue’s effective-TING INSTRUMENTS, etc.; Lakoff & John-

son, 1980), recognizing the vehicle’s literal ness in prompting recall of a metaphorical andliteral use (e.g., She prepared a three-coursecategory, ‘‘food’’ in this case, is crucial. In

principle, the activation of ‘‘food’’ knowledge meal for her guests) should be equivalent. If,on the other hand, the metaphorical use ofto understand the metaphorical use of three-

course meal should occur in the same way as three-course meal is understood to name acategory that can include the topic (‘‘thingsits activation when understanding the term in

a literal context, as in She prepared a three- that come in large quantities’’), then a cuedescribing the attributive category (largecourse meal for her guests. The difference is

that in a metaphorical context, the IDEAS quantity) should be effective.ARE FOOD correspondences are also acti-

Methodvated (Lakoff, 1993). This view suggests thatan appropriate cue for recalling the metaphor Participants. Thirty-eight Princeton under-

graduates were paid for their participation inwould be one that makes reference to the CMsource domain (e.g., food). the experiment. Thirty-six participated in the

recall phase, and 2 served as coders in theAccording to the AC view, the literal cate-gories of the topic and vehicle are not central recall scoring phase.

Materials. Sixteen pairs of sentences wereto metaphor meaning. When a metaphor isunderstood, the representation that is gener- created for this experiment. One sentence of

each pair was metaphorical, created by choos-ated is an attributive category that is exempli-fied by the vehicle and may plausibly include ing topics and vehicles from domains that CM

theorists have described. For example, Thethe topic. For example, when people encoun-ter The lecture was a three-course meal, they faculty meeting was a battle instantiates the

conceptual metaphor ARGUMENT IS WARmay initially recognize three-course meals’status in the ‘‘food’’ category, but quickly dis- (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The literal control

sentence for this metaphor was Many men tookregard this category because it cannot include

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$24 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

558 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

part in the battle. The various subjects and phrases. Half of these pairs were the cue pairsdesigned for the recall experiment (e.g., bodypredicates across the sentence pairs were kept

as distinct as possible. From these metaphori- part—intelligent, food—large quantity, etc.).The other 16 pairs were constructed by scram-cal–literal pairs, two acquisition lists were

constructed such that only one sentence of bling the cue pairs (e.g., body part—exciting,war—large quantity, etc.). Participants wereeach pair appeared in a list, and each list con-

tained equal numbers of the experimental sen- instructed to rate each pair on a seven-pointrelatedness scale (with ‘‘1’’ labeled as ‘‘nottence types. The assignment of sentences to

lists was made in a way judged likely to mini- at all related’’ and ‘‘7’’ labeled as ‘‘very re-lated’’). The cue pairs and scrambled pairsmize intralist intrusions. In addition to the ex-

perimental sentences, the lists included six lit- were presented in a random order in the book-let. The mean relatedness ratings for the cueeral filler sentences, three at the beginning and

three at the end. These sentences were in- pairs and scrambled pairs were 3.03 and 2.61,a difference which was not reliable (t(19) Åcluded in the lists to control for potential pri-

macy and recency effects in subsequent recall. 2.01, p ú .20). This suggests that the cueswere sufficiently distinct to differentiate be-Both lists were recorded on audiotape by an

adult male speaker, using a natural speaking tween retrieval of a CM-based and an AC-based encoding of a metaphor.pace and intonation contour. Each sentence

was spoken twice, with a 5-s pause between The cues were assembled into two sets, witheach set containing half of the CM cues andeach utterance.

Two sets of words were generated as recall half of the AC cues. The CM and AC cues fora given sentence always appeared in differentcues. One set was designed to cue the CM

source domains from which the vehicle terms lists. The order of the cues in each list wasrandomized with respect to acquisition order,were chosen. For example, the sentence Lisa

is the brain of the family was designed to in- and the same order was used in both lists toprevent differential recall order effects. Book-stantiate the conceptual metaphor SOCIAL

GROUPS ARE BODIES. To cue the source lets that presented each cue in boldface lettersat the top of an otherwise blank sheet of paperdomain of ‘‘bodies,’’ the term body part was

chosen as a CM cue. The AC cues referred were prep.Procedure. Participants were run in groupsto the attributive category associated with the

vehicle concept. For example, if brain is un- of two in a single experimental session. Bothparticipants sat in a small experimental roomderstood to be emblematic of an attributive

category (‘‘intelligent things’’), then a word facing a tape recorder placed on a table infront of them. The experimenter informeddescribing the category (intelligent) should be

an effective recall cue. Other CM and AC cues them that they would hear a series of unrelatedsentences describing various types of people,were generated using this logic.

Although an effort was made to keep the ideas, emotions, and objects. Participants wereasked to listen carefully to each sentence asCM and AC cues as distinct as possible, there

were some cases in which the two cues were it was read. No mention was made of the sub-sequent recall task. After playing one of thesemantically related to some degree. For ex-

ample, the CM and AC cues for the metaphor two acquisition lists, the experimenter pre-sented participants with one of the two book-The faculty meeting was a battle were war

(ARGUMENTS ARE WAR) and dispute lets of recall cues. Participants were instructedto read each cue word carefully and to write(‘‘situations involving a dispute’’). To deter-

mine the overall level of semantic relatedness down any of the presented sentences to whichthe cue word seemed to be related. Partici-of the cue pairs, a group of 20 Lafayette Col-

lege undergraduates were recruited for a sepa- pants were explicitly told not to worry aboutrecalling the proper names that were used inrate norming study. Each participant received

a booklet containing 32 pairs of words and some of the sentences (e.g., Lisa is the brain

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$24 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

559METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

TABLE 1 ducted on the individual proportions with Sen-tence Type (literal vs metaphorical) and CueRECALL ACCURACY AS A FUNCTION OF SENTENCE AND

CUE TYPE, EXPERIMENT 4 Type (CM vs AC) as within-subject andwithin-item factors. Initial analyses did not

Sentence type reveal significant acquisition list or cue listCue

effects, so further analyses were conductedtype Literal Metaphoricalcollapsing across these factors. There were no

Strict scoring CM 0.49 0.20 significant differences between the analysesAC 0.31 0.41 for the strict and gist scoring criteria, so only

Gist scoring CM 0.56 0.25 the analyses on the gist data are reported.AC 0.36 0.49

Analyses of these data revealed no significantmain effects of either Sentence Type or CueType. There was, however, a strong Sentenceof the family). The experimenter paced partici-Type X Cue Type interaction (Fs(1,35) Åpants at 45 s per cue.28.38, p õ .01; Fi(1,15) Å 12.65, p õ .01).Recall scoring. The recall protocols for

Planned comparisons to examine the rela-each participant were coded using two differ-tive effectiveness of the AC and CM cues inent sets of scoring criteria. The ‘‘strict’’ scor-prompting recall of the metaphorical and lit-ing criteria required that each recalled sen-eral sentences were conducted. AC cues weretence be a reproduction of the stimulus sen-more effective in prompting recall of the met-tence, with the following exceptions:aphorical sentences than CM cues (ts(35) ÅDeletion, addition, or changes of articles;5.41, p õ .01; ti(15) Å 2.79, p õ .02). Forchanges in number and gender of pronouns;example, The lecture was a three-course mealchanges of auxiliary verbs; changes of tense;was more effectively prompted by a cue de-changes of word order; and substitution ofscribing the attributive category exemplifiedproper names with pronouns. The ‘‘gist’’ scor-by the vehicle (large quantity) than by a terming criteria included all of the exceptionsreferring to the CM source domain (food). Al-above and also allowed for substitution of syn-though this finding suggests that the AC cuesonyms and hyponyms (e.g., ‘‘food’’ for three-provided a better match than the CM cues tocourse meal), the omission of one or morethe representations that were generated duringsentence elements (e.g., ‘‘Lisa is a brain’’ formetaphor comprehension, there is an alterna-Lisa is the brain of the family), or the introduc-tive explanation that should be considered.tion of new elements. The gist scoring in-The CM cues may have been less effectivecluded all sentences counted as correct recallsbecause they were poorly chosen—i.e., theby the ‘‘strict’’ scoring.CM cues failed to capture the ‘‘essence’’ ofTwo additional participants coded the recallthe CM source domain. However, the effec-protocols after studying a two-page descrip-tiveness of the CM cues in prompting recalltion of the scoring criteria and an example listof the literal sentences (mean recall accuracyof scored sentences. The coders scored theÅ 0.56) does not support this conclusion.protocols independently and upon first com-Overall, CM cues were significantly more ef-parison had a 91% agreement rate. Disagree-fective than AC cues in prompting recall ofments were resolved through discussion be-the literal sentences (ts(35) Å 2.61, p õ .02;tween coders and, when necessary, throughti(15) Å 2.37, p õ .05). For example, foodthe input of a third party.was a more effective cue than large quantity

Results and Discussion when three-course meal appeared in a literalcontext (She prepared a three-course meal forThe mean proportions of sentences cor-

rectly recalled as a function of sentence type, her guests). Apparently, the membership ofthree-course meals in the ‘‘food’’ categoryrecall cue, and scoring criteria are presented

in Table 1. Analyses of variance were con- was more salient when it appeared in a literal

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$24 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

560 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

context, and its membership in the ‘‘large guistic device is obvious. New or abstract con-cepts are most likely to be understood whenquantity’’ category was more salient in the

metaphorical context. they can be assimilated into concepts that arefamiliar or concrete. Metaphor provides com-The results from this experiment parallel

those of Anderson and Ortony’s (1975) classic municators with a compact way to convey thisgiven–new or concrete–abstract relationship.study of contextual influence on the accessi-

bility of word senses. These researchers dem- The fundamental role that metaphor playsin communication has led some theorists toonstrated that the mental representation cre-

ated by reading a word or phrase is not invari- conclude that metaphor also plays a funda-mental role in human thought. The CM viewant across sentences, but rather particularized

by context. For example, consider the repre- formulated by Lakoff and his colleagues isone such theory, although other researcherssentations of ‘‘piano’’ that might be created

upon reading one of the following sentences: have made similar claims (Clark, 1973; Trau-gott, 1978). The role that these hypothesizedPianos can be pleasing to listen to; Pianos

can be difficult to move. Pianos’ musical po- conceptual structures may play in humanthought and reasoning is beyond the scopetential is relevant in the first sentence, and

their status as heavy pieces of furniture is rele- of this article. The experiments reported herefocus exclusively on the role that conceptualvant in the second sentence. Anderson and

Ortony concluded that the differential effec- metaphors may play in the interpretation ofmetaphorical expressions. The most parsimo-tiveness of cue words in prompting recall of

these sentences (music was effective for the nious conclusion that can be drawn from ourresults is that people’s interpretations of meta-first, heavy for the second) was an indication

of the different representations of piano that phors are not necessarily related to an underly-ing conceptual metaphor. Three pieces of evi-are generated when the term is encountered

in different contexts: ‘‘. . . in one context, dence support this conclusion. First, peopledo not modally paraphrase metaphors in CMpiano is a member of the same category as,

say, harmonica while . . . in the latter case terms (Experiments 1 and 2). Second, meta-phors with a common CM derivation are notperhaps sofa would be a cohyponym’’ (p.

169). This explanation is in principle similar perceived as more similar than those with nosuch relation (Experiment 3). Third, terms de-to the AC explanation of the recall findings

in this experiment. In a literal context, a con- scribing the relevant CM source domain arerelatively ineffective cues for metaphor recall.cept’s salient taxonomic category member-

ships are salient, but when the concept is used Our failure to find a reliable influence ofconceptual metaphors on people’s interpreta-as a metaphor vehicle, they may not be. In-

stead, the category that is accessed is one that tions may have resulted from factors unique toour experiments. At a minimum, two factorsthe vehicle exemplifies and may plausibly in-

clude the topic. should be considered. First, our participantsencountered metaphors in isolation (i.e., with-

GENERAL DISCUSSION out a supporting context). This situation maybe contrasted with those in which people en-Scholars have noted the ubiquity of meta-

phor not only in conversation and literature, counter figurative expressions in contexts thatfacilitate recognition of an underlying meta-but also in such diverse areas as psychother-

apy (Rothenberg, 1984), religion (Soskice, phoric theme (Albritton, McKoon, & Gerrig,1995; Nayak & Gibbs, 1990). In these situa-1985), and physics (Gentner & Gentner,

1983). The pervasiveness of metaphor in vari- tions, people may very well employ CM-cor-respondences in their interpretations. For ex-ous discourse contexts led Ortony (1975) to

conclude that metaphors are not simply nice, ample, Nayak and Gibbs (1990) found thatreaders consider the idiom blow your top tothey are necessary. While the ‘‘necessity’’ of

metaphor is debatable, the utility of this lin- be more appropriate than bite someone’s head

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$25 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

561METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

off in a story containing other ANGER IS can be interpreted as an assertion that the topictheir lawyer belongs to a category of thingsHEATED FLUID UNDER PRESSURE idi-

oms (Lakoff, 1987). At the very least, this that the vehicle shark exemplifies. The cate-gory that the vehicle is taken to exemplify willfinding suggests that people can appreciate the

metaphoric consistency of different idiomatic be determined by its stereotypical properties.Since sharks are stereotypically ‘‘vicious,’’expressions. However, this finding does not

force the conclusion that mental reference to the term shark can be understood as a refer-ence to a category of ‘‘vicious beings.’’ Otheranger–heat correspondences is necessary to

understand blow your top. Appropriateness concepts that share the property ‘‘vicious’’(and thus exemplify the category of ‘‘viciousjudgments are the product of a deliberate, con-

scious thought process and thus do not consti- beings’’), such as wolf or piranha, may besubstituted for shark without producing an ap-tute a measure of the knowledge that used

is during on-line comprehension (Glucksberg, preciable change in the way their lawyer ischaracterized.Brown, & McGlone, 1993).

The present experiments also suffer from While the present results are consistent withthe attributive categorization view, a fewthis problem—paraphrasing, similarity rating,

and cued recall are not on-line measures. Con- words of qualification are in order. First,Glucksberg (1991) proposed the attributivesequently, our results cannot address Lakoff’s

(1993) claim that conceptual metaphors are categorization model to describe metaphor in-terpretation strictly at the level of discourse.used ‘‘constantly and automatically’’ in any

interpretational context. It is possible, for ex- The view is moot with respect to the formand structure of the mental lexicon and mayample, that people rely on conceptual meta-

phors during immediate metaphor comprehen- require modification as future research eluci-dates the role that this structure plays in dis-sion but do not have introspective access to

this information when they attempt to verbal- course comprehension. Second, the AC viewdoes not in any way ‘‘solve’’ the problem ofize their interpretations. Introspective failures

of this sort have been documented in the study metaphor interpretation. Rather, it recasts theproblem in terms of categorization constructsof attitudes (e.g., Nisbett & Wilson, 1977) and

may also have occurred in our experiments. that are familiar to cognitive psychologists.Conceptualizing the problem in these termsIn the absence of relevant on-line evidence,

however, explaining our results in these terms does, however, offer clear implications forwhat an adequate psychological model of met-would be premature.

If conceptual metaphors are used during on- aphor interpretation might look like. Such amodel would specify how people process mul-line comprehension, their influence does not

manifest itself in the interpretations people tiple category memberships that the topic andvehicle concepts have in common, and howproduce in situations conducive to reflection.

In the situations we examined, people appear people select the category that is relevant ina given discourse context.to rely heavily on the stereotypical properties

of the vehicle concept. This finding is consis- In conclusion, the attributive categorizationview does not spill the beans on metaphortent with previous studies of metaphor inter-

pretation (Gentner & Clement, 1988; Ortony, interpretation. It does, however, offer somefood for thought.Vondruska, Foss, & Jones, 1985; Tour-

angeau & Rips, 1991) and is consistent with APPENDIX Athe attributive categorization view described

Stimulus Metaphors Usedby Glucksberg (1991). According to this view,in Experiments 1–3metaphors are understood as category-inclu-

sion assertions in which the topic is assigned 1. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a 3-coursemeal for the mind.to a category exemplified by the vehicle con-

cept. For example, Their lawyer is a shark (IDEAS ARE FOOD)

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$25 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

562 MATTHEW S. MCGLONE

2. Our marriage was a rollercoaster ride. times things were good and sometimesbad.(LOVE IS A JOURNEY)

3. Complex theories often have leaky 5. We had a very frenetic relationship.plumbing. 6. We were aroused and thrilled by one an-(THEORIES ARE BUILDINGS) other in our marriage.

4. The singer’s voice was velvet. 7. Our marriage was an exciting, electrifying(SOUND IS TOUCH) experience.

5. Our relationship is a filing cabinet. 8. We would go from good days to bad days.(RELATIONSHIPS ARE CONTAIN- Our marriage was very passionate.ERS) 9. Our feelings changed from love to hate

6. Tine planted the seeds of discontent very quickly.among the members of her office pool. 10. Our marriage was exhausting and emo-(IDEAS ARE PLANTS) tional.

7. Her mind is a shoebox. 11. We were very unstable in our feelings for(MINDS ARE CONTAINERS) one another.

8. Our love is a voyage to the bottom of the 12. A thrilling and dangerous experience.sea. 13. Sometimes we love one another, some-(LOVE IS A JOURNEY) times we hated one another, but we al-

9. The faculty meeting was a battle. ways aroused each other.(ARGUMENT IS WAR) 14. Our marriage was stimulating and emo-

10. Billboards are warts on the landscape. tional.(LAND IS A BODY) 15. We would have good days and bad days.

11. Our relationship has been a storm.16. The marriage exhausted us because our

(LOVE IS A PHYSICAL FORCE)emotions changed so quickly.

12. The professor breathed new life into17. We exited one another, and had veryMary’s thesis.

strong passions.(IDEAS ARE PEOPLE)18. Like a rollercoaster, our marriage was ex-13. Lisa is the brain of the family.

citing and stomach-turning at the same(SOCIAL GROUPS ARE BODIES)time.14. Alan has a heart of ice.

19. Things happened so quickly in our mar-(EMOTIONS ARE TEMPERATURES)riage that we didn’t have time to breathe.15. Tom’s novel is the caviar of the book

20. We were emotionally unstable in our mar-world.riage.(IDEAS ARE FOOD)

21. Our marriage was very passionate, excit-16. Karen really gets John’s motor running.ing, and dangerous.(LUST IS A MACHINE)

22. Our marriage was charged with passion.23. We loved and hated each other, but weAPPENDIX B

always excited one another.Paraphrases (Unedited) Generated

24. Our marriage bounced around from loveby Participants in Experiment 1

to hate.25. We waited a long time to get married, but1. Our marriage was a rollercoaster ride.

it was definitely worth the wait.1. Our marriage was always exciting, but26. We had some good times, but we also hadsome days were happier than others.

some very bad times.2. We were emotionally up and down all of27. Our marriage was happy and sad, thrillingthe time.

and boring.3. The marriage was extremely exciting andpassionate. 28. Our marriage aroused the best and worst

of feelings in us.4. Our marriage was pretty unstable, some-

AID JML 2441 / a001$$$$26 07-02-96 22:47:17 jmla AP: JML

563METAPHOR INTERPRETATION

29. Our marriage was never very stable emo- 28. We are deep in love.29. It is unpassionate and cold.tionally.

30. It was a frantic, shaky marriage. 30. Our love is a journey on uncharted seas.

APPENDIX C2. Our love is a voyage to the bottom of thesea. Paraphrases (Unedited) Generated

1. Our love is exciting and mysterious. by Participants in Experiment 22. Our love is pretty novel and strange.3. We discover new things about each other 1. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a three-course

the deeper we fall in love. meal for the mind.4. Our love is unlike any we have ever 1. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was full of infor-

known. mation.5. Our love is a very private affair, away 2. The lecture was an intellectual rose gar-

from the rest of the world. den.6. It is a long journey to an unknown desti- 3. Dr. M’s lecture was exercise for the brain.

nation. 4. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was the ‘‘War and7. Our love is silent and still. Peace’’ of lectures.8. Our love is takes us away from the rest 5. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was overflowing

of the world. with information.9. We are doomed if we stay together. 6. Dr. Moreland’s lecture was a buffet for