Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

-

Upload

aleksandra-kulpa -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

0

Transcript of Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

1/14

An update on TeotihuacanGeorge L. Cowgill

At Antiquitys invitation the author offers this account of recent research and current objectivesat the famous ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan. After a century of investigationarchaeologists are beginning to see something of the composition and preoccupations of on Americas rst urban societies, and how it began, ourished and ended.

Keywords:Mesoamerica, Teotihuacan, rst millennium CE, state formation, state collapse,governance, iconography, writing

IntroductionTeotihuacan is a great ancient city, located 2250m above sea level in the cool and semi-ariduplands of Central Mexico (Figure 1). It ourished between about 100/1 BC and AD550/650, long predating the Aztecs. During much of that time it covered 20km2, with apopulation near 100 000 or possibly more. It is a key site for the study of the rise of urbanismand the creation of state societies.

Teotihuacan is much too large to be owned by any one group, and investigations aresteadily being carried out by scholars from many institutions, Mexican, US, Canadian,

Japanese, French and others. I have tried to cover recent literature in English and Spanish,but I cannot claim to be comprehensive. Cowgill (1997; 2000a; 2003; 2007) are shortoverviews. Pasztory (1997), Carrascoet al . (2000), Sugiyama (2005) and Headrick (2007)are recent books in English. Collections primarily in Spanish include Brambila and Cabrera(1998), Manzanilla and Serrano (1999), Ruiz (2002), Ruiz and Soto (2004) and Ruiz andTorres Peralta (2005). Reports of projects sponsored by the Foundation for the Advancementof Mesoamerican Studies are at www.famsi.org. I have emphasised publications notmentioned in any of these sources, and only sparingly mentioned unpublished work inprogress.

New projects: Pyramid of the MoonThe most noteworthy recent project at Teotihuacan (Figure 2) is that carried out at theMoon Pyramid between 1998 and 2004, directed by Saburo Sugiyama of Aichi PrefecturalUniversity and Arizona State University and Ruben Cabrera of the Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia (INAH). Sugiyama and Cabrera explored the interior and exterior of this second-largest Teotihuacan pyramid (168 149m at its base and 46m high) and foundseven construction stages. The earliest, a small platform 23.5 23.5m at the base, dating School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287-2402, USA

(Email: [email protected]) ANTIQUITY 82 (2008): 962975

962

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

2/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

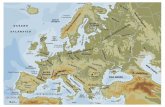

Figure 1. Mesoamerica: 1) Teotihuacan; 2) Tula; 3) Monte Alb an; 4) Xochicalco; 5) Cholula; 6) Matacapan; 7) CerroBernal; 8) Cop an; 9) Kaminaljuy u; 10) Tikal.

somewhere between 100 BC and AD 100, is currently the earliest well-known structureat Teotihuacan. The pyramid was subsequently greatly enlarged in a series of buildingstages, of which the latest, probably dating to around AD 350, is the one now visible. Fourundisturbed major tombs were found, each with one or more sacriced humans and many animal victims, as well as rich offerings of precious stone, obsidian and other materials(Figure 3). One tomb included objects strongly suggestive of long-distance interactions with elites in the Maya lowlands. No evidence of durable structures was found on top of the successive construction stages of the pyramid. It seems their upper surfaces were largeelevated platforms where rituals and other activities could be witnessed by crowds at groundlevel.

These results were summarised in a special section of Ancient Mesoamerica(2007) andmore recently in unpublished papers at the 2008 AnnualMeetingof the Society for American Archaeology in Vancouver. Sugiyama and Lopez Lujan (2006) is the catalogue for anexhibition of spectacular nds from the most recently discovered tomb.

Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent Sugiyama (2005) describes and interprets nds at the Feathered Serpent Pyramid (alsoknown as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl), within the 16ha Ciudadela complex, mostly from

963

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

3/14

An update on Teotihuacan

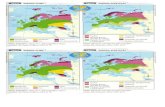

Figure 2. Teotihuacan: 1) Ciudadela and Feathered Serpent Pyramid; 2) Sun Pyramid; 3) Moon Pyramid; 4) Xalla;5) Great Compound; 6) La Ventilla District; 7) Tlajinga 33; 8) 15B:N6W3; 9) Cosotlan 23; 10) San Jos e 520 (approximate location);11)Teopancaxco; 12)Tetitla; 13) Oaxaca Enclave;14) Merchants Enclave; 15)19:N1W5,a residential compound with west Mexican ties (after Millon 1973, copyright Millon 1972).

excavations in 1988-89. It was probably built around AD 200, contemporary with laterstages of the Moon Pyramid. It is the third largest pyramid at Teotihuacan (65 65mat the base and about 20m high) and it is notable for the cut stone apron-and-panel(talud-tablero) facades on all four sides, with three-dimensional sculptures of feathered

serpents and other motifs. Nearly 200 bound sacricial victims were found there inundisturbed mass burials. Many were young men with military accoutrements; others were young women and a few were older males accompanied by rich offerings. The soldiersmight be captive enemies, but the quality of their attire and their emplacement as if intended to protect the pyramids contents suggest to me that they may have beenelite guards for a royal household. Stable oxygen isotope analyses suggest that many wereforeigners. There are many historically known cases where rulers preferred foreigners asguardsmen.

Whether one or more monarchs were buried at the Feathered Serpent Pyramid remainsan unresolved question because a large pit under the pyramid and another just in front of its stairway were looted at some time in the past, and almost entirely emptied. The few

964

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

4/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

Figure 3. Small greenstone gures from Tomb 3 of the Moon Pyramid (courtesy of Saburo Sugiyama).

remaining scraps offer some suggestions that these pits contained rulers, but the evidence ishighly ambiguous.

Not long after completion of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid, perhaps around AD 300, itsuffered desecratory damage. Burned fragments of large moulded clay motifs that apparently adorned a perishable structure that had stood on top of it were thrown into the ll of a large

stepped platform that was now built over most of its front (west) facade. The size of thisnew platform implies that activities on a fairly large scale continued to be carried out withinthe Ciudadela complex, probably seen by crowds in the complexs central plaza. Other sidesof the Feathered Serpent Pyramid remained visible but in disrepair, and there was possibly a hiatus in construction activities in the large apartment complexes that adjoined it on thenorth and south. Construction in the Ciudadela was resumed late in Teotihuacans history,and remains of censers diagnostic of the nal Teotihuacan ceramic phase (Metepec) werefound broken in place on the surface of the latest concrete oor at the rear of the FeatheredSerpent Pyramid. Fallen carved stones from the pyramids facade were found at various levels within the rubble above this latest oor, indicating that actual collapse of the pyramid took place gradually after the fall of the Teotihuacan state.

965

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

5/14

An update on Teotihuacan

New interpretations: governance and elitesIn spite of the quality of the tombs found at the major pyramids, none of those interredseems to have been a ruler, and it remains unclear whether the Teotihuacan state was headedby monarchs or governed through other political institutions. The rapid growth of early

Teotihuacan and the scale and audacity of its pyramids and its orderly layout all suggest thatearly leaders possessed great ambition and strong power; yet there is no obvious evidence thatthey were celebrated in physically enduring monuments. But this paradox may be illusory. Inthe Indus civilisation of south Asia, evidence of rulers is so elusive that some have questioned whether it counts as a state. Yet, the uniformity of the Indus weights over a vast area suggestsan extremely strong overarching authority, considering how variable weights and measures were within European states until the adoption of the metric system. Furthermore, the low prole of early Teotihuacan potentates tends to be seen in contrast to the Classic period Mayaemphasis on portraits of rulers and glyphic accounts of their deeds and pedigrees. Mayakings may be toward the high end of the comparative scale in this regard, possibly becauseof their limited actual power. Early Teotihuacan rulers may have been too powerful to needsuch public celebration, and the immense pyramids they sponsored may have been all they required by way of monuments. Alternatively, representations of Teotihuacan rulers may actually be present, but misidentied and unrecognised (Cowgill 1997; Headrick 2007).

The cessation of the construction of huge new structures after about AD 250 and thedesecration of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid soon thereafter hint at major changes in thepolitical system of Teotihuacan. Perhaps new institutions made rulers more accountable toelite councils. Conceivably, election from among eligible high elites by these councillorsreplaced inheritance of ofce.

Excavations by Manzanilla (2006) and Lopez Lujan et al . (2006) at the Xalla complex,somewhat east of the Avenue of the Dead and somewhat north of the Sun Pyramid, may also have a bearing on the matter of Teotihuacan governance. This complex is unlike any other at Teotihuacan, and its function remains enigmatic.

The broad low platforms of the Great Compound, across the Avenue of the Dead fromthe Ciudadela, enclose a possible marketplace. Not far south-west is the district called LaVentilla, composed of several residential compounds, where a project directed by Cabrerain 1992-94 (Cabrera Castro 2000; Gomez Chavez 2000) excavated all or parts of severalcompounds. It is unlikely that any were occupied by holders of the highest ofces inTeotihuacan society, but the quality of construction in at least two, and parts of a third,suggests occupation by lesser elites. Some apartments in one compound have smaller rooms,are less nely constructed, and include debris from work in semi-precious stones and othermaterials. One suspects the presence of attached specialists.

City planning The highly accurate map produced by Rene Millons Teotihuacan Mapping Project in the1960s and 70s demonstrates that Teotihuacan was exceptionally orthogonal. Even today,a country road about 1km outside the ancient city adheres within a few minutes (not justdegrees) to the canonical orientation of 15.5 east of astronomical north. Cowgill (2000b)

966

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

6/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

suggested that the presently-observed plan developed over time and questions whether it wasfully conceived from the beginning. In any case, the fact that the orientation was followedso closely throughout the entire city suggests a strong central authority. Furthermore, evenif the original plan was modied by later additions, the resulting layout is harmonious.MacDonalds (1986) term, armature, for the layouts of Roman cities may be applicable.

Treating the city as a whole, Ian Robertson (1999; 2005) has applied innovativemultivariatestatistics andBayesianmethods to Teotihuacan Mapping Project data, to discernspatial patterns of socio-economic status throughout the city, and their changes over time.He nds that neighbourhoods tended to be heterogeneous, though with some tendency for higher proportions of high status people towards the centre and lower proportions of high status residents toward the edges. Neighbourhoods seem to have become less internally diverse over time, which may have led to greater social tensions. He also addresses issues of top-down planning versus bottom-up self-organisation.

Teotihuacan society Understanding the whole society was one goal of Millons mapping project. However, it wasalways recognised that that project was only an early step that needed to be followed up with more intensive surface surveys and excavations in selected localities.

Nothing is known about Teotihuacan non-elite residential architecture before about AD250, but Plunket and Urunuela (2002) and Urunuela and Plunket (2007) describe likely antecedents in the nearby Valley of Puebla. Some multi-apartment residential compounds were among the rst structures to be excavated at Teotihuacan. However, they were usually selected for the presence of indicators of high quality, such as polychrome wall-paintings.There was an unfortunate tendency to label them palaces, but in fact there is a continuumof material quality, ranging from quite high to quite low, and emphasis has turned towardstudying the whole range. Perhaps the highest level outside the civic-ceremonial core isrepresented by some of the compounds in the recent work in the La Ventilla district by Cabrera and his group. Other compounds in that district, such as La Ventilla B, are probably toward the low end of the scale. Probably still lower on the scale, but no less interesting, isthe site called San Jose 520, an architecturally very modest complex on the extreme south-eastern outer margin of the city, where excavations by Oralia Cabrera have found goodevidence of pottery production. The occupants may have been socially as well as spatially

marginal possibly newcomers in the process of being incorporated into the urban society.In the Tlajinga district, also in the southern part of the city but somewhat less marginal,other potters specialised in production of a distinctive utility ware called San Martn Orange.Excavations at one compound there have led to important palaeodemographic data (Storey 1992) as well as data on craft production. Kristin Sullivan (2006) has conducted statisticalanalyses of the ceramic industry in this district, where potters apparently worked at anindependent household level of organisation. More recently she hascarried outvery intensivesurface survey of Cosotlan 23, an apartment compound in the north-west part of thecity, where independent specialists produced ceramic gurines and mould-made censerornaments. She has compared them with the ornaments produced by attached specialists inan enclosure adjacent to the Ciudadela.

967

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

7/14

An update on Teotihuacan

Other examples of recent excavations at various intermediate socio-economic levels,often carried out from a household archaeology point of view, include those of LindaManzanilla at 15B:N6W3 in the north-western Oztoyahualco district (Manzanilla 1993)and at Teopancaxco, somewhat south-east of the Ciudadela (Manzanilla 2006). Barbaet al .(2007) discuss commoner ritual.

Although they follow the Teotihuacan canonical orientation and are organised intoapartments generally built around a central patio or court, many of these intermediate tolower quality compounds are otherwise not highly organised internally. Their outer limitsdo not always form neat rectangles, and several show good evidence that their boundarieschanged over time. The notion that they are highly standardised is a myth that depends ontoo strong a focus on a few supposedly typical examples and which, like other myths, gainsauthority with the telling and re-telling.

Foreigners within the city

Millons mapping project discovered two districts with signicantly high proportions of ceramics either imported from other regions or locally-made but stylistically foreign: anOaxaca Enclave toward the western edge of the city and a Merchants Enclave on thenorth-eastern margin, with ceramics imported from the Gulf lowlands and from the Mayalowlands. Subsequent excavations in both districts, most recently in the Oaxaca Enclave by Michelle Croissier, of the University of Illinois, have conrmed and amplied the evidencefor foreigners, and Sergio Gomez Chavez (2002) reports good evidence of migrants fromthe state of Michoacan, in western Mesoamerica, in a residential compound not far eastof the Oaxaca Enclave. At the Tetitla compound, mural paintings, including fragments of

Maya glyphs, attest a Maya presence (Taube 2003). A puzzle is that local versions of early Oaxacan ceramic types seem to have continued tobe made for several centuries after they ceased to be produced in the homeland. Emigrantsoften preserve old practices for decades or even more than a century after they have goneout of use in the source region, but the apparent duration of superseded types in the OaxacaEnclave seems exceptional and is in need of further testing. In a long series of papers Whiteet al . (e.g. 2004), Spenceet al . (2005), Wright (2005) and Priceet al . (2000) report on stableisotope studies on the provenance of migrants. Recent publications on enclaves and ethnicity are by Spence (1996; 2002; 2005). It is not surprising that a city as large and importantas Teotihuacan would have been ethnically diverse, but the reasons for these migrants andtheir roles in Teotihuacan society are not yet well understood.

Art, iconography, calendrics and astronomy

From an art-historical point of view Pasztory (1997) concludes that Teotihuacan was autopian social experiment, that it deliberately adopted a masked inscrutability, and thatthe pantheon was headed by a well-dened Great Goddess. I nd this interpretationunconvincing. Teotihuacan was probably not utopian in any reasonable sense of thatterm. Because Teotihuacan did not adopt anything like the well-developed script of thecontemporary Maya (although Teotihuacanos were surely aware of that script) and insteadrelied on a number of standardised signs whose meanings are still mostly unknown, it

968

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

8/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

presents all the usual difculties of understanding ancient societies in the absence of texts.For these signs Taube (2000) is a major synthesis, including important data on occurrencesof Teotihuacan signs outside the core region. Most signs remain enigmatic or partially understood. Further work on them is strategic for better understanding of all aspects of Teotihuacan thought and practice, including religious and political concepts, titles andofces. I do not think Teotihuacanos deliberately set out to be inscrutable to one another ortheir neighbours, and their remains seem more scrutable than those of Neolithic or Bronze Age Europe. There were female deities in the Teotihuacan pantheon, but the notion of anoverarching goddess has been tellingly criticised by Paulinyi (2006).

Using high-precision total station measurements, Sugiyama (2008) provides convincingevidence that the dimensions of major structures along the Avenue of the Dead embody key numbers that show use of the widespread Mesoamerican sacred cycle of 260 days, thevague year of 18 months (of 20 days) plus 5 extra days, and very likely other astronomicalcycles and even the Long Count of the Maya.

Work on artefacts, art and iconography proceeds apace. Important recent work includes work on obsidian technology by David Carballo (2007; Carballoet al . 2007) and Bradford Andrews (2002; 2006), a two-volume compendium of Teotihuacan mural paintings editedby Beatriz de la Fuente (1995) and studies of polychrome stuccoed cylinder vases by CynthiaConides (1997; 2001). Rattray (2001) is a great advance in our knowledge of Teotihuacanceramics and their chronology, but it is far from the last word on this topic and more work is urgently needed. Scott (2001) has produced a volume on the very numerous previously unpublished gurines from Sigvald Linnes excavations in the 1930s.

Headrick (1999; 2001; 2007) derives important political implications from Teotihuacaniconography. Sprajc (2000) discusses astronomical alignments. Aveni (2005) updates andreconsiders pecked crosses and other motifs, concluding that they were not likely used forTeotihuacan alignments but more probably for calendrical rituals, divination and perhapsto some extent for games.

Palaeoenvironmental studiesMcClung (2005), McClung et al . (2003; 2005) and Solleiro-Rebolledoet al . (2006) reportrecent work. But this is a topic in urgent need of further development, especially in the lightof current concerns about human environmental impacts and the role of environmental

factors in the rise and fall of societies.

Outside the city Teotihuacan controlled, or at least was very inuential over, a territory of culturally similarpopulations covering at least a 60km radius from the city (Figure 4). Within this corearea regional centres such as Azcapotzalco, Axotlan, Cuauhtitlan and Cerro Portezuelo weremuch smaller than Teotihuacan, but far larger than villages and differed considerably amongthemselves. Far beyond that, Teotihuacan presences, generally of ambiguous signicance,occur throughout most of Mesoamerica. The Teotihuacan polity was not a city-state inanything like the sense of Bronze Age Mesopotamia or Classical Greece and is better

969

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

9/14

An update on Teotihuacan

regarded as a regional state. At its peak it may have controlled enough people over largeenough distances to have qualied as an empire.

Figure 4. The Basin of Mexico.

Little work at Teotihuacan-related sites within the core region has been published.However, several projects are reported inRuiz and Torres Peralta (2005). Projectsrecently completed or in progress includethat by Thomas Charlton and CynthiaOtis Charlton at nearby sites in theupper Teotihuacan Valley (Charlton &Otis Charlton 2007) and Raul Garca at Axotlan, near Cuauhtitlan, in the north- western Basin of Mexico. Cowgill andDeborah Nichols (of Dartmouth College),

aided by Arizona State University doctoralstudents Sarah Clayton andDestiny Crider,are directing a collaborative project to study materials from excavations in the 1950sby George Brainerd at Cerro Portezuelo, aTeotihuacan provincial centre about 30kmsouth of the city, reported in unpublished

papers at the 2008 Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Vancouver.Teotihuacan probably focused on the control of places for strategic and/or commercialreasons rather than on the administration of large continuous blocks of territory. Onesuch strategic spot is Matacapan, in the Gulf lowlands of southern Veracruz, where asignicant Teotihuacan connection is clear, although its strength was exaggerated by thelate Robert Santley. In highland Oaxaca, the Zapotec state resisted Teotihuacan expansionand apparently dealt with it on equal terms. Joyce (2003) suggests a stronger Teotihuacanconnection in coastal Oaxaca, plausibly one source of the Pacic shells widely used atTeotihuacan.

Teotihuacan presence is evident at Mirador in central Chiapas and strongly markedby stelae in Teotihuacan style at Cerro Bernal (Los Horcones), near the Pacic coast of Chiapas, strategically located on the way to the cacao-producing Soconusco region of coastal

Chiapas and Guatemala (Taube 2000). Work here by Claudia Garca-Des Lauriers (2007) isproviding fuller information. In coastal Guatemala, Bove and Medrano (in Braswell 2003)report Teotihuacan-related sites, some quite early.

Long-known Teotihuacan connections at Kaminaljuy u in the Maya highlands and atTikal and Copan in the lowlands are reassessed in the volume edited by Geoffrey Braswell(2003). Most chapters in that book are biased toward interpretations that minimise theimpact of Teotihuacan on the Maya. David Stuart and William and Barbara Fash (inCarrasco et al . 2000) are less sceptical. Hattula Moholy-Nagy (1999) describes utilitarianand ritual obsidian objects from Central Mexico found at Tikal. Some other claims of allegedTeotihuacan connections at sites in the Maya lowlands are based on rather imsy evidenceand betray poor understandings of genuine Teotihuacan styles. Koszkulet al .s (2007) good

970

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

10/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

report of Teotihuacan-related nds at Nakum is a welcome exception. Interaction wentboth ways; Clayton (2005) discusses INAA evidence about source areas represented by Maya ceramics found during various periods at Teotihuacan.

There were Teotihuacan inuences in parts of western Mexico, as well as evidence of westerners in the city itself, but connections to the west and north do not seem as strong assuggested in some earlier publications (e.g. Aveniet al . 1982). The west was a large regionof dynamic independent societies.

The collapse of Teotihuacan and its aftermathThe collapse of ancient societies has been a thread in archaeological thought for some time,but interest is broadening to consider aftermaths of collapses as well (Schwartz & Nichols2006). Jared Diamond (2005) has provoked very mixed reactions among archaeologists butthe issues he raises must be addressed especially the extent to which a research emphasis

on interactions between humans and physical environments neglects or oversimpliesrelations of humans with one another. Explanations for the decline and collapse of theTeotihuacan state must consider the relative roles of internal social factors, external enemies,environmental factors and possibly climate change. Understanding the roles of risingcentres such as Xochicalco in the state of Morelos; Cacaxtla-Xochitecatl, Cholula andCantona in Puebla/Tlaxcala; and Tula in Hidalgo continues to be impeded by impreciseceramic chronologies. Manzanilla (2006), drawing especially on her recent work at theTeopancaxco apartment compound (somewhat south-east of the Ciudadela), suggests thatlate in Teotihuacans history, intermediate-level elites gained increasing wealth and powerthat was independent of the central authority. This would have weakened the state andcould have played a large role in its collapse. This is an attractive idea, especially in view of similar processes documented elsewhere, as in the rise and fall of dynasties in imperialChina.

There is very active work on the Epiclassic period,c . AD 650-850, just after thecollapse of the Teotihuacan state. Recent publications bearing on the Epiclassic in CentralMexico are Manzanilla (2005) (especially chapters on her and her students work in cavesor underground chambers east of the Sun Pyramid), Beekman and Christensen (2003),Nichols etal . (2002), Sugiura (2005), Solar Valverde (2006) and Crideretal . (2007). Sharply contrasting and strongly felt opinions are currently expressed concerning the possibility that

migrants into Central Mexico may have had a large role in collapse of the state. Somesee much evidence for continuity and think the collapse due mainly to internal factors.But there is disagreement over such a basic factual issue as the degree of persistence inthe Epiclassic of ceramic features derived from those of terminal Teotihuacan, versus thosederived from elsewhere. Resolution of this issue is one precondition for meaningful debateon issues such as migration and identity. But, even with this question of ceramic continuity or disjunction settled, there will remain issues about the extent to which ceramic changesreect migrations, shifts in ethnic identity, or simply adoption of new styles topics currently debated by archaeologists working in many regions. Resolution is likely to come less fromfeatures of artefacts, architecture and settlement patterns than from bioarchaeological data,especially stable isotopes and hopefully DNA.

971

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

11/14

An update on Teotihuacan

Linguistics offers yet another source of evidence. The language of the Aztecs was Nahuatl.If it could be shown that Nahuatl was already the principal language of Teotihuacan elites,it would suggest a relatively minor role for migrants in the collapse of the Teotihuacanstate. Most arguments for the great antiquity of Nahuatl in Central Mexico have relied ontenuous evidence and the mere assertion that cultural continuity into Aztec times was toogreat to make large in-migrations plausible. Actually, while many features of Aztec thoughtand religion have Teotihuacan antecedents, many other Teotihuacan features did not longsurvive its political collapse.

Dakin and Wichman (2000) argue that a Maya word for cacao, the source of chocolate,attested in early Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions, wasborrowedfrom Nahuatl. This seemingly strengthens the case for early Nahuatl at Teotihuacan. But Kaufman and Justeson (2007)argue strongly that the word for cacao cannot have been derived from Nahuatl, and wasmore likely borrowed from a language of the unrelated Mixe-Zoquean family. They ndmany other words borrowed from Mixe-Zoquean into a number of Mesoamerican languages

during the right time interval, and suggest that the language of Teotihuacan elites was very likely Mixe-Zoquean. This shifts the balance back toward a sizable in-migration of Nahuatl-speakers around the time of Teotihuacans collapse. However, we surely have not heard thelast word on this contentious issue.

References Ancient Mesoamerica. 2007. Special Section: recent

archaeological research at the Moon Pyramid,Teotihuacan. Ancient Mesoamerica18(1): 107-90.DOI:10.1017/S0956536107000156.

A NDREWS, B. 2002. Stone tool production atTeotihuacan: what more can we learn from surfacecollections?, in K. Hirth & B. Andrews (ed.)Pathways to prismatic blades: a study in Mesoamerican obsidian core-blade technology : 47-60.Los Angeles (CA): Cotsen Institute of Archaeology,University of California.

2006. Skill and the question of blade crafting intensity at Classic period Teotihuacan, in J. Apel &K. Knutsson (ed.)Skilled production and social reproduction: aspects of traditional stone-tool technologies . Uppsala: Societas ArchaeologicaUpsaliensis & Department of Archaeology and

Ancient History, Uppsala University. A VENI, A.F. 2005. Observations on the pecked cross andother gures carved on the south platform of thePyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan.Journal for the History of Astronomy 36: 31-47.

A VENI, A.F., H. H ARTUNG & J.C. K ELLEY . 1982. AltaVista (Chalchihuites): astronomical implications of a Mesoamerican ceremonial outpost at the Tropicof Cancer. American Antiquity 47: 316-35.

B ARBA , L., A. ORTIZ & L. M ANZANILLA . 2007.Commoner ritual at Teotihuacan, Central Mexico,in N. Gonlin & J.C. Lohse (ed.)Commoner ritual and ideology in ancient Mesoamerica: 55-82. Boulder(CO): University Press of Colorado.

BEEKMAN, C.S. & A.F. CHRISTENSEN. 2003.Controlling for doubt and uncertainty throughmultiple lines of evidence: a new look at theMesoamerican Nahua migrations.Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 10: 111-64.

BRAMBILA , R. & R. C ABRERA (ed.). 1998. Los Ritmos de

Cambio en Teotihuac an: reexiones y discusiones de sucronologa. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

BRASWELL, G.E. (ed.) 2003. The Maya and Teotihuacan:reinterpreting Early Classic interaction. Austin (TX):University of Texas Press.

C ABRERA C ASTRO, R. 2000. Teotihuacan culturaltraditions transmitted into the Postclassic accordingto recent excavations, in D. Carrasco, L. Jones &S. Sessions (ed.)Mesoamericas Classic heritage: fromTeotihuacan to the Aztecs : 195-218. Boulder (CO):University Press of Colorado.

C ARBALLO

, D.M. 2007. Implements of state power: weaponry and martially themed obsidianproduction near the Moon Pyramid, Teotihuacan. Ancient Mesoamerica18: 173-90.

C ARBALLO, D.M., J. C ARBALLO& H. N EFF. 2007.Formative and Classic period obsidian procurementin Central Mexico: a compositional study usinglaser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-massspectrometry. Latin American Antiquity 18(1): 2-43.

C ARRASCO, D.M., L. JONES & S. SESSIONS (ed.). 2000. Mesoamericas Classic heritage: from Teotihuacan tothe Aztecs . Boulder (CO): University Press of Colorado.

972

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

12/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

CHARLTON , T.H. & C. O TIS CHARLTON . 2007. En lascercanas de Teotihuacan: inuencias urbanasdentro de comunidades rurales, in P. Fournier, W. Wiesheu & T.H. Charlton (ed.) Arqueolog a y complejidad social : 87-106. Mexico City: EscuelaNacional de Antropologa e Historia & InstitutoNacional de Antropologa e Historia.

CLAYTON , S.C. 2005. Interregional relationships inMesoamerica: interpreting Maya ceramics atTeotihuacan. Latin American Antiquity 16:427-48.

CONIDES , C.A. 1997. Social relations among potters inTeotihuacan, Mexico. Museum Anthropology 21:39-54.

2001. The stuccoed and painted ceramics fromTeotihuacan, Mexico: a study of authorship andfunctions of works of art from an ancientMesoamerican city. Unpublished PhD dissertation,Columbia University.

COWGILL , G.L. 1997. State and society at Teotihuacan,Mexico. Annual Review of Anthropology 26: 129-61.

2000a. The Central Mexican highlands from the riseof Teotihuacan to the decline of Tula, inR.E. Adams & M.J. MacLeod (ed.)The Cambridge history of the native peoples of the Americas.Volume II: Mesoamerica, Part 1: 250-317.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2000b. Intentionality and meaning in the layout of Teotihuacan, Mexico. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 10: 358-61.

2003. Teotihuacan: cosmic glories and mundaneneeds, in M.L. Smith (ed.)The social construction of ancient cities : 37-55. Washington (DC):Smithsonian Institution Press.

2007. The urban organization of Teotihuacan,Mexico, in E.L. Stone (ed.)Settlement and society:essays dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams :261-95. Los Angeles (CA) & Chicago (IL): CotsenInstitute of Archaeology, University of California,and Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

CRIDER , D., D.L. NICHOLS , H. NEFF &M.D. GLASCOCK . 2007. In the aftermath of Teotihuacan: Epiclassic pottery production and

distribution in the Teotihuacan Valley, Mexico.Latin American Antiquity 18(2): 123-43.D AKIN, K. & S. W ICHMAN . 2000. Cacao and chocolate.

Ancient Mesoamerica11(1): 55-75.DE LA FUENTE, B. (ed.) 1995.La Pintura Mural

Prehisp anica en M exico I: Teotihuac an. Mexico City:Instituto de Investigaciones Esteticas, UniversidadNacional Autonoma de Mexico.

DIAMOND , J. 2005. Collapse: how societies choose to fail or succeed . London: Allen Lane (Penguin edition2006) & New York: Viking.

G ARCIA -DES L AURIERS, C. 2007. Proyecto arqueologicoLos Horcones: investigating the Teotihuacanpresence on the Pacic coast of Chiapas, Mexico.Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of California, Riverside.

GOMEZ CH AVEZ, S. 2000.La Ventilla: un barrio de la

antigua ciudad de Teotihuac an. Mexico City:Escuela Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.2002. Presencia del occidente de Mexico en

Teotihuacan. Aproximaciones a la poltica exteriordel Estado Teotihuacano, in M.E. Ruiz Gallut (ed.)Ideologa y poltica a traves de materiales, im agenes y smbolos : 563-625. Mexico City: UniversidadNacional Autonoma de Mexico & InstitutoNacional de Antropologa e Historia.

HEADRICK , A.1999. The Street of the Dead: it really was: mortuary bundles at Teotihuacan.Ancient Mesoamerica10: 69-85.

2001. Merging myth and politics: the Three Templecomplex at Teotihuacan, in R. Koontz,K. Reese-Taylor & A. Headrick (ed.)Landscape and power in Ancient Mesoamerica: 169-95. Boulder(CO): Westview Press.

2007. The Teotihuacan trinity: the sociopolitical structure of an ancient Mesoamerican city . Austin(TX): University of Texas Press.

JOYCE, A.A. 2003. Interregional interaction and socialdevelopment on the Oaxaca coast.Ancient Mesoamerica14: 67-84.

K AUFMAN, T. & J. JUSTESON. 2007. The history of the word for cacao in ancient Mesoamerica.Ancient Mesoamerica18(2): 193-237.

K OSZKUL, W., B. HERMES & Z. C ALDER ON . 2007.Teotihuacan-related nds from the Maya site of Nakum, Peten, Guatemala. Mexicon28(6): 117-27.

LOPEZ LUJ AN, L., L. FILLOY N ADAL, B. F ASH, W.L.F ASH & P. H ERN ANDEZ. 2006. The destruction of images in Teotihuacan: anthropomorphic sculpture,elite cults, and the end of a civilization.Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 49/50: 13-39.

M ACDONALD , W.L. 1986. The architecture of the RomanEmpire II: an urban appraisal . New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

M ANZANILLA , L. (ed.) 1993.Anatoma de un conjuntoresidencial Teotihuacano en Oztoyahualco. MexicoCity: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas,Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

2005 (ed.) Reacomodos demogr acos del Cl asico al Poscl asico en el centro de M exico. Mexico City:Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas,Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

2006. Estados corporativos arcaicos. Organizacionesde excepcion en escenarios excluyentes.Cuicuilco13(36): 13-45.

973

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

13/14

An update on Teotihuacan

M ANZANILLA , L. & C. SERRANO (ed.). 1999. Pr acticas funerarias en la Ciudad de los Dioses: los enterramientos humanos de la antigua Teotihuacan.Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas, Universidad Nacional Autonomade Mexico.

MCCLUNG DE T APIA , E. 2005. Enfoques biologicos enla arqueologa de Teotihuacan y la cuenca deMexico, in E. Vargas Pacheco (ed.)IV ColoquioPedro Bosch Gimpera: el occidente y centro de M exico:253-72. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas, Universidad Nacional Autonomade Mexico.

MCCLUNG DE T APIA , E., E. SOLLEIRO-R EBOLLEDO , J. G AMA -C ASTRO, J.L. V ILLALPANDO & S. SEDOV .2003. Paleosols in the Teotihuacan Valley, Mexico:evidence for paleoenvironment and human impact.Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geol ogicas 20: 270-82.

MCCLUNG DE T APIA , E., I. DOMINGUEZ R UBIO , J. G AMA -C ASTRO, E. SOLLEIRO & S. SEDOV . 2005.Radiocarbon dates from soil proles in theTeotihuacan Valley, Mexico: indicators of geomorphological processes.Radiocarbon47(1):159-95.

MILLON, R.1973. The Teotihuacan map. Part 1: text. Austin (TX): University of Texas Press.

MOHOLY -N AGY , H. 1999. Mexican obsidian at Tikal,Guatemala. Latin American Antiquity 10: 300-13.

NICHOLS , D.L., E.M. BRUMFIEL, H. NEFF, M. HODGE ,T.H. C HARLTON & M.D. GLASCOCK . 2002.Neutrons, markets, cities, and empires: a 1000-yearperspective on ceramic production and distributionin the Postclassic basin of Mexico.Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 21: 25-82.

P ASZTORY , E. 1997. Teotihuacan: an experiment in living .Norman (OK): University of Oklahoma Press.

P AULINYI, Z. 2006. The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan: ction or reality?Ancient Mesoamerica17(1): 1-15.

PLUNKET, P. & G. URUNUELA . 2002. Shrines, ancestors,and the volcanic landscape at Tetimpa, Puebla, inP. Plunket (ed.) Domestic ritual in Ancient Mesoamerica: 32-42. Los Angeles (CA): Cotsen

Institute of Archaeology, University of California.PRICE, T.D., L. M ANZANILLA & W.D. M IDDLETON .

2000. Immigration and the ancient city of Teotihuacan in Mexico: a study using strontiumisotope ratios in human bone and teeth.Journal of Archaeological Science 27: 903-13.

R ATTRAY , E.C. 2001. Teotihuacan: ceramics, chronology and cultural trends . Mexico City & Pittsburgh (PA):Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia &University of Pittsburgh.

R OBERTSON , I.G. 1999. Spatial and multivariateanalysis, random sampling error, and analyticalnoise: empirical Bayesian methods at Teotihuacan,Mexico. American Antiquity 64: 137-52.

2005. Patrones diacronicos en la constitucion de losvecindarios teotihuacanos, in M.E. Ruiz Gallut &

J. Torres Peralta (ed.)Arquitectura y urbanismo: pasado y presente de los espacios en Teotihuacan:memoria de la tercera mesa redonda de Teotihuacan:277-94. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

R UIZ G ALLUT, M.E. (ed.) 2002. Ideologa y poltica atraves de materiales, im agenes y smbolos. Memoria de la primera mesa redonda de Teotihuacan. MexicoCity: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico& Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

R UIZ G ALLUT, M.E. & A.P. SOTO (ed.). 2004. La Costadel Golfo en tiempos Teotihuacanos: propuestas y perspectivas.Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

R UIZ G ALLUT, M.E. & J. TORRES PERALTA (ed.). 2005. Arquitectura y urbanismo: pasado y presente de los espacios en Teotihuacan. Mexico City: InstitutoNacional de Antropologa e Historia.

SCHWARTZ , G.M. & J.J. NICHOLS (ed.). 2006. After collapse: the regeneration of complex societies . Tucson(AZ): University of Arizona Press.

SCOTT , S. 2001.The corpus of terracotta gurines fromSigvald Linnes excavations at Teotihuacan, Mexico(1932 & 1934-35) and comparative material (Monograph Series 18). Stockholm: NationalMuseum of Ethnography.

SOLAR V ALVERDE, L. (ed.) 2006.El fen omenoCoyotlatelco en el centro de Mexico. Mexico City:Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

SOLLEIRO-R EBOLLEDO, E., S. SEDOV , E. MCCLUNGDE T APIA , H. C ABADAS, J. G AMA -C ASTRO &E. V ALLEJO-GOMEZ . 2006. Spatial variability of environmental change in the Teotihuacan Valley during the Late Quaternary: paleopedologicalinferences.Quaternary International 157: 13-31.

SPENCE, M.W. 1996. A comparative analysis of ethnic enclaves, in A.G. Mastache, J.R. Parsons,

R.S. Santley & M.C. Serra Puche (ed.)Arqueolog a Mesoamericana: homenaje a William T. Sanders :333-53. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

2002. Domestic ritual in Tlailotlacan, Teotihuacan, inP. Plunket (ed.) Domestic ritual in Ancient Mesoamerica: 53-66. Los Angeles (CA): CotsenInstitute of Archaeology, University of California.

2005. A Zapotec diaspora network in Classic-PeriodCentral Mexico, in G. J. Stein (ed.)The archaeology of colonial encounters: comparative perspectives :173-205. Santa Fe (NM): School of AmericanResearch.

974

-

8/8/2019 Teotihuacam -mapa!!!!

14/14

R e s e a r c h

George L. Cowgill

SPENCE, M.W., C.D. W HITE , E.C. R ATTRAY &F.J. LONGSTAFFE . 2005. Past lives in different places:the origins and relationships of Teotihuacansforeign residents, in R.E. Blanton (ed.)Settlement,subsistence, and social complexity: essays honoring the legacy of Jeffrey R. Parsons : 155-97. Los Angeles(CA): Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

SPRAJC, I. 2000. Astronomical alignments atTeotihuacan, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity 11:403-15.

STOREY , R. 1992. Life and death in the ancient city of Teotihuacan: a modern paleodemographic synthesis .Tuscaloosa (AL): University of Alabama Press.

SUGIURA , Y. 2005. Y atr as qued o la Ciudad de los Dioses:historia de los asentamientos en el Valle de Toluca.Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas, Universidad Nacional Autonomade Mexico.

SUGIYAMA , S. 2005.Human sacrice, militarism, and rulership: the symbolism of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacan, Mexico. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

2008. Teotihuacan city layout as a cosmogram:architectural and measurement-unit study from theMoon Pyramid. Paper presented at the 73rd AnnualMeeting of the Society for American Archaeology,Vancouver, 26-30 March 2008.

SUGIYAMA , S. & L. LOPEZ LUJ AN (ed.). 2006. Sacricios de consagraci on en la Pir amide de la Luna. MexicoCity: Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

SULLIVAN, K.S. 2006. Specialized production of SanMartn Orange Ware at Teotihuacan, Mexico.Latin American Antiquity 17: 23-53.

T AUBE, K.A. 2000.The writing system of ancient Teotihuacan. Barnardsville (NC) & Washington(DC): Center for Ancient American Studies.

2003. Tetitla and the Maya presence at Teotihuacan,in G.E. Braswell (ed.)The Maya and Teotihuacan:reinterpreting Early Classic interaction: 273-314. Austin (TX): University of Texas Press.

URUNUELA , G. & P. PLUNKET. 2007. Tradition andtransformation: village ritual at Tetimpa as atemplate for early Teotihuacan, in N. Gonlin & J.C. Lohse (ed.)Commoner ritual and ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica: 33-54. Boulder (CO):University Press of Colorado.

W HITE , C.D., M.W. SPENCE, F.J. LONGSTAFFE &K.R. L AW . 2004. Demography and ethniccontinuity in the Tlailotlacan Enclave of Teotihuacan: the evidence from stable oxygenisotopes.Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 23:385-403.

W RIGHT, L.E. 2005. In search of Yax Nuun Ayiin I:revisiting the Tikal Projects burial 10.Ancient Mesoamerica16: 89-100.

975