115qs

-

Upload

ujangketul62 -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

Transcript of 115qs

-

8/8/2019 115qs

1/6

The paper by Kuhn and Youngberg1 in

this issue ofQSHCtakes an historical

approach to the evolution of riskmanagement, following it from past fail-

ures into the path for its future success.The essence of the change will occur

with the primary goal of risk manage-

ment moving from the protection of the

financial concerns of the organisation tothe protection of its patients in terms of

improved safety and quality of care. Fordecades risk management has sat uneas-

ily beside quality systems, and it is only

with the integration of these systemsinto one which has good patient care as

its ultimate goalclinical governance in

the UKthat there is the possibility ofsuccess.

Nevertheless, while the structural in-tegration of quality systems may be rela-

tively straightforward, the psychological

integration of the concepts of quality =good and error = bad will take much

longer to address. It is this splitting off of

painful anxiety about real or potentialerrorsthe fear, guilt and shame that it

involves2 3which lays in the uncom-

fortable unconscious of health care and

which makes the task of risk manage-ment so difficult. Many years ago Isobel

Menzies-Lyth conducted her seminal

exploration of the ways in which health-care organisations and professions struc-

ture themselves and their procedures in

order to protect themselves from theanxiety associated with caring for dis-

tressed, diseased, and dying patients.4

Her work is embedded primarily in the

provision of good care; however, accept-

ing that error is not rare but a strongpossibility for all individuals and that

such error can lead to the very distress,disease, and death that we strive to

relieve, cure or avoid may make the

anxiety she explores potentially unbear-able. Our new risk management depends

upon the open discussion of error but, as

we saw in Bristol, defences against anxi-ety are likely to create new barriers toseeing and accepting this error.

I would suggest that it is these barriersagainst anxiety which have until nowstopped risk management being success-fully integrated into the whole system ofimproving patient care: risk managers

have traditionally been kept physicallyseparate from other systems, seen assomething of a joke, a burden clinicianssometimes have to bear, interested onlyin the tedious. These are the defences ofa staff hard pressed, often under-resourced and, not surprisingly, unwill-ing to get involved with the anxiety pro-

voking idea that error is an ordinary

everyday event.

It is the splitting off ofpainful anxiety about real

or potential errors . . .

which makes the task of riskmanagement so difficult

The addressing of near misses is seen

as an essential part of the new riskmanagement5 and should make the

discussion of error less difficult by focus-

ing on potential rather than actual prob-lems. However, there is also the argu-

ment that people adapt their behaviour

more determinedly when a failure ordisaster has happened to them rather

than to someone else. For example, those

in the town next to one hit by hurricaneHugo did little to protect their homes

from future hurricanes, while those inthe damaged town built strong defences

for the future.6 7 A focus on near missesseems intuitively as useful in health care

as it was in air travel, but we simply do

not know the extent to which this will beoffset by a lack of salience to over-

stretched staff. This, along with so many

of the fundamental questions aboutpatient safety, shows the need for a wellfunded and carefully considered pro-gramme of research for this crucial area.

The authors focus upon leadership asone way towards the new culture whereerror will be discussed and addressed

within the whole system rather than byindividual staff members. As they sug-gest, leaders need to attend not just to

thefinancial business case butalso to themoral one if they are to succeed inproviding better patient safety. Thismoral case will include leaders taking onissues of trustfor example, that pa-tients will be told the truth, that staff

will be treated justly, and systems will betackled to change what went wrong.Trust will be engendered through clarityabout accountability, through honesty,and by consistency on the part of theleaders concerned.8 Finally, these leadersneed to be aware of the anxiety faced bystaff and by themselves in the provisionof health care. It is so easy for a ChiefExecutive to avoid seeing what clinicians

and patients have to face daily in theirorganisation, but it will not help trust todevelop if they do.

Anxiety is thus a fundamental part ofhealth care; not something we canchange but something to be aware of sothat the defences we build against it donot end up making the risk managementof the future as unsuccessful as that ofthe past.

Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:115

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to: Professor J Firth-Cozens,London Deanery, 20 Guilford Street, LondonWC1N 1DZ, UK;

REFERENCES1 Kuhn AM, Youngberg BJ. The need for risk

management to evolve to assure a culture ofsafety. Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:15862.

2 Leape LL, Woods DD, Hatlie MJ, et al.Promoting patient safety by preventingmedical error. JAMA 1998;280:1444.

3 Davidoff F. Shame: the elephant in the room.Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:23.

4 Menzies-Lyth I. Containing anxiety ininstitutions. London: Free Associations Press,1988.

5 Department of Health. An organisation witha memory. Report of an Expert Group onLearning from Adverse Events in the NHSchaired by the Chief Medicial Officer.London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

6 Firth-Cozens J. Cultures for improving patientsafety through learning: the role of teamwork.Qual Health Care2001;10(suppl II):ii2631.

7 Norris FH, Smith T, Kaniasty K. Revisiting theexperience behavior hypothesis: the effects ofhurricane Hugo on hazard preparedness andother self-protective acts. Basic Appl SocPsychol1999;21:3747.

8 Firth-Cozens J, Mowbray D. Leadership andthe quality of care. Qual Health Care2001;10(suppl II):ii37.

Risk management. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Anxiety as a barrier to riskmanagementJ Firth-Cozens. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Leaders need to recognise that anxiety is an inevitable part ofcaring for patients and that, without the building of trust, itmay affect risk management by reducing the reporting oferror.

COMMENTARIES 115

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 115qs

2/6

The historical summary of risk man-

agement by Kuhn and Youngberg1 inthis issue of QSHC concludes with

the provocative challenge: Those r isk

managers who accept change and thinkof new ways to embed risk management

principles into their organization to help

create meaningful and sustainablechange will prosper. Those who dont

should get out now. They are destined to

fail and to fail their organizations.This judgment may be a bitpremature,

too focused on the individual risk man-ager, and actually reverse cause andeffectthat is, rather than a need for

risk management to evolve to assure aculture of safety, perhaps theopposite is

true. Is it possible that a culture of safety

(high reliability) is the necessary prereq-uisite for allowing risk management to

evolve? It is possible that, in a highly

reliable safety culture, the risk manage-ment function as outlined by Kuhn and

Youngberg may turn out to have minimal

functional usefulness.Svedung and Rasmussen2 have re-

cently suggested that the following con-

siderations are necessary for effective

management of future risk:(1) It is . . . becoming increasingly dif-

ficult to explain accident causation by

(retrospective) analysis of local factors within a work system. Safety and risk

management increasingly become socio-

technical system problems (rather thanthe study of accidents themselves).

(2) A very aggressive and competitiveenvironment tends to focus the incen-

tives of decision makers on short term

financial criteria rather than on longterm criteria concerning welfare, safety

and environmental impact . . . court

reports from several recent accidents

show that they have not been caused bycoincidence of independent failures and

human errors but by a systematic migra-tion of organizational behavior toward

accidents under the influence of pressure

toward cost effectiveness in an aggres-sive competitive environment.

(3) Risk management has been reac-tive and primarily guided by studies ofpast accidents and incidents. It is sug-gested that future risk managementstrategies be based not on analysis ofaccidents, but rather on normal workpractices and sociocultural factors thatshape those work practices in an actual

work place. It is therefore entirely possi-ble that the ultimate root cause of anyaccident is production pressure, theorigins of which lie outside the do-main(s) currently considered manage-

able in the framework proposed byYoungberg and Kuhn.

This is not to suggest that risk transferand claims resolution will cease to beimportant corporate functions. Health-care accidents are, after all, accidents.

While it may be possible to decrease theprobability of an accident occurring,given the complexity of human natureand technology that are integral to thedelivery of health care, mishaps willremain a natural part of our delivery sys-tem. Indeed, as Kuhn and Youngbergpoint out, the ability to negotiate risktransfer agreements with steadily de-clining costs contributes operating capi-tal and increased margins, both of whichhave been shown to decrease mortality,thereby increasing patient safety andmitigating risk.3

Kuhn and Youngberg raise the inter-esting question: How could we (riskmanagers) have worked so hard andaccomplished so little? This question inturn creates others. How can anyoneknow what has not been accomplished?How is it possible to measure accidentsor injury that have been prevented andtherefore did not occur? It is impossibleto know what the total cost of risk wouldhave been had an attempt to manage

healthcare risk (even with paradigmssuggested as not effective) not beenundertaken.

When pricing and rates are soft, the very hard work of negotiating favorableterms ironically ensures that incentivesdo not exist to thwart what the German

sociologist Ulrich Beck has described asan acceptance of uncertainty and or-

ganized irresponsibility.4 By contrast,the prediction of dramatic environmen-

tal change such as the twin tower disas-ter in New York on 11 September 2001

that leads to an industry wide knee jerk

reaction is no more the purview of indi- vidual risk managers than of corporate

senior management itself.

Indeed, some responsibility for what-ever proposed shortcomings are inherent

in the current model of healthcare risk

management must include corporategovernance and accountability by senior

management. As Kuhn and Youngberg

point out, managing risk is about corpo-rate design and improvement and

changing systems of work rather thansimply a staff function assigned to an

office or someone labelled risk manage-

ment. Integrating the work of risk intoorganizational and managerial culture

and making it an explicit step in the

decision making process is critical to

future successful management of corpo-rate healthcare risk.

Managing future risk is not, as sug-gested by Kuhn and Youngberg, about

embedding risk management principles

into healthcare organizationsthat is,reporting for the purpose of analyzing,

characterizing and trending accidents,incidents and near misses. Rather, it is

about replacing current risk manage-

ment principles with those found inorganizational development, the social

sciences, financial modelling, knowledge

management, and story telling. The cha-otic and complex nature of healthcare

risk suggests that anything else will fall

short.

Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:116

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to: Dr G E Knox, Director,Patient Safety, Childrens Hospitals and Clinics,2525 Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis, MN55404, USA; [email protected]

REFERENCES1 Kuhn AM, Youngberg BJ. The need for risk

management to evolve to assure a culture ofsafety. Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:15862.

2 Svedung I, Rasmussen J. Graphicrepresentation of accident scenarios: mappingsystem structure and the causation ofaccidents. Safety Sci2002;40:397417.

3 Shortell SM, Rousseau DM, Giles RR, et al. Anational program to improve the quality ofICU services. Final report submitted to theHealth Care Financing Administration, April1991.

4 Beck U. Risk society: towards a newmodernity. London: Sage, 1992.

Risk management. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Risk management or safety first?G E Knox. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Is a culture of safety the necessary prerequisite for allowingrisk management to evolve?

116 COMMENTARIES

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 115qs

3/6

The determinants of health and ill-

ness are not just biological, nor is a

persons response to injury or illness.Patients live in families and communi-

ties of various types. They often work in

less than healthy or even in hazardousoccupations, and they relax in activities

that may be health promoting or not.

Patients live within a larger political, cul-tural, and environmental context that

further affects both them and theirfamilies or communities. All of these

less biological aspects of a patients life

influence his or her state of health orcondition of illness. Indeed, health and

illness are integrated phenomenathatis, they integrate biological, social andcultural, economic, political, occupa-

tional and environmental, recreational

and other aspects of an individuals life.The specific health effect of these dispa-

rate influences is complex and often is

much more important than traditionalhealth care has factored into customary

approaches to diagnosis and treatment.As Coulter so clearly espouses in her pre-

scription for patient centred care,1 cogni-zance of these patient related factors is

crucial for effective treatment.Coulters prescription for redesigning

health services is sound and timely, asfar as it goes. The need for puttingpatients at the centre of the healthcare

universe may have been especially high-

lighted by the unfortunate events at theBristol Royal Infirmary,2 but the need to

redesign the healthcare delivery systemto be more responsive to the perspectives

and needs of patients is evident every

day in clinics, hospitals, nursing homes,and other care facilities throughout the

delivery system. Restructuring health-

care delivery to be patient centred willrequire a fundamental transformation of

healthcare operations, which will neces-sitate a sustained and concerted effortand which will be accompanied by a cer-tain amount of pain. If successfullyexecuted, however, the end result will bemore effective use of time and resources,reduced costs, improved coordinationand continuity of care, and better out-comes. If done correctly, the transforma-tion to a patient centred healthcaredelivery system will substantially im-prove the quality of care, as viewed byboth patients and caregivers, and it willalmost certainly decrease the per patientcost of care.

A key element in redesigning thehealthcare system to be more patientcentred will be preserving and, in manycases, enhancing the caregiver-patientrelationship.This intimate relationship isthe medium by which information, feel-ings, fears, concerns, and hopes areexchanged between caregiver and pa-tient. The integrity of this relationship isfoundational for successful diagnosisand treatment. It is also a key determi-nant of how satisfying is the care experi-ence for both patient and caregiver.Indeed, the process of interaction be-tween caregiver and patient is often themost therapeutic aspect of the health-

care encounter.While recognising the essentiality of

transforming health care to be morepatient centred for all the reasons that

were articulated by Coulter, we also mustbe mindful that, just as health is an inte-grative phenomenon, so is health care.Indeed, health care involves complexrelationships between and amongcaregivers and with the ambient envi-ronment that significantly impacts ontherapeutic outcomes.

Modern health care is the mostcomplex activity ever undertaken by

human beings. It involves highly compli-cated technology that can seriously harmas well as miraculously heal. It is a teamactivity with more than 80% of thehands-on care being provided by non-physicians. The myriad of specialisedcaregivers are often focused on only oneaspect of the patients care, so there aremany care hand offs among them.Information about the technical aspects

of care must be communicated and actedupon by the various caregivers in a coor-dinated manner. These complex andmultifaceted interactions need to beorchestrated in consistent and predict-able ways that are mutually satisfying toboth patient and caregiver. This is asocial process that is subject to thecultural, economic, and political dimen-sions inherent to the care processes.

Just as the determinants of health andillness are not just biological, the deter-minants of health care are neither justbiological nor just technical. Health careis an integrated phenomenon that has itsown social, cultural, economic, and po-

litical dimensions that are often asimportant, or more so, than the technicaldimensions on which we more oftenfocus. Effective health care must inte-grate the biological, technical,social, cul-tural, economic, political, and otheraspects of both patients and caregivers.These dimensions of care have to beintegrated into the systems of care. Weneed to view health care as beingprovided by treatment families, treat-ment teams, or therapeutic communi-ties, as opposed to something done byindividual caregivers. Just as with pa-tients families and communities, healthcare families and communities mayoperate with varying degrees of func-tionality and be more or less effective.

Unfortunately, the dynamics of therelationships that caregivers have witheach other and with the larger therapeu-tic communities in which they practicehave not yet been well studied and areonly rarely addressed in healthcareteaching. To improve the likelihood thatthe various therapeutic entities will pro-mote health care, caregivers need to betrained in techniques of team basedproblem solving and team based caremanagement. These are areas that haveonly recently begun to be addressed in

health care, with nursing and anesthesiabeing the most progressive so far.

35

Models of such include aviation stylecrew resource management, MedTeams,and anesthesia crisis management.Health care must also address the cul-tural and political contexts of care itselfand how these interface with the largersocietal, cultural and political contexts,each of which may facilitate or impedeoptimal therapeutic outcomes. Again,only recently have we begun to rigor-ously analyse and experiment with thesedimensions of the care process.6 7

Patient centred care. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Patient centred care: essential butprobably not sufficientK W Kizer. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

One of the many lessons to emerge from the analysis of thecare of children in the cardiac unit at the Bristol RoyalInfirmary is the importance of engaging patients in decisionsabout their health and health care. This is a message that hasrelevance to all healthcare professionals in all clinical settings.Patient centredness is crucial for good quality care, butachieving genuine patient centred care throughout healthservices will require transformation of systems as well asattitudes. In this issue (pp 1868) we have reproduced AngelaCoulters paper After Bristol: putting patients at the centre,first published in the BMJ in March 2002.

COMMENTARIES 117

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 115qs

4/6

The patient centred model of care is

essential because it promotes a whole

person approach to care that recognizesthe larger context in which patients live

and function. However, it alone is notlikely to be sufficient because it does not

explicitly embrace the interdisciplinary

and sociocultural nature of health careitself. The integrative nature of health

care will have to be addressed if health

care is truly to operationalize the patientcentred model of care and if we are to

achieve the improvement in healthcare

quality that is so much needed.

Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:117118

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to: K W Kizer, President andChief Executive Officer, The National QualityForum, Washington, DC, USA;[email protected]

REFERENCES1 Coulter A. After Bristol: putting patients at the

center. BMJ2002;324:64851.2 Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. Learning

from Bristol: the report of the public inquiry

into childrens heart surgery at the BristolRoyal Infirmary 19841995. London:Stationery Office, 2001; http://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk (accessed5 February 2001).

3 Byrne AJ, Sellen AJ, Jones JG, et al. Effects ofvideotape feedback on anaesthetists

performance while managing simulatedanesthetic crises: a multicentre study.Anaesthesia 2002;57:16982.

4 Zinober JW. Building a sense of teamworkwithin the organization. Getting along with

your practice partners. Med Group Manage J1991;38:369.

5 Hetherington LT. Becoming involved: thenurse leaders role in encouraging teamwork.Nurs Admin Q1998;23:2940.

6 Rafferty AM, Ball J, Aiken LH. Are teamworkand professional autonomy compatible, and

do they result in improved hospital care? QualHealth Care2001;10:327.7 Ratto M, Propper C, Burgess S. Using

financial incentives to promote teamwork inhealth care. J Health Serv Res Policy2002;2:6970.

Asignificant proportion of medical

activity is based on custom andpractice rather than on sound evi-

dence of effectiveness. It is a matter of

concern worldwide to understand howbest to encourage doctors to stop doing

things that dont work. The paper byBlack and Hutchings1 in this issue ofQSHC offers a fascinating account of the

time trends in rates of surgery for glueear and the possible impact of the 1992

Effective Health Care bulletin which out-

lined the reasons to doubt the effective-ness of this common surgical

procedure.2

Rates of glue ear surgery in NHS hos-

pitals, which were already falling slowly

before the bulletin appeared, fell from120 per 10 000 in 1992/3 to 68 per 10 000

in 1997/8. The fall in intervention rateremains significantthough less

dramaticwhen private hospital activity

is taken into account. Several contextualfactors are identified to explain why the

message of the Effective Health Care

bulletin did not fall on deaf ears: adownward trend had already begun as

both otolaryngologists and GPs were

beginning to doubt the value of grom-mets, media reports of these doubts were

influencing parents readiness to request

referral, and the purchaser/provider split

encouraged closer scrutiny of the effec-tiveness of interventions. A further con-textual factor not brought out by theauthors is the relative freedom of theBritish healthcare system from fee forservice incentives for medical activity ofdubious worth.

Experience from another studysuggests that the rate of referral by gen-eral practitioners for glue ear fell by 50%during this period, but practitioners inboth primary care and hospital inter-

viewed in a separate qualitative studyreported little awareness of or influenceby the Effective Health Care bulletin.3 Wecannot always easily identify whatmakes us change what we do, and when

we do change our practice we are some-times reluctant to acknowledge, even toourselves, that we have done so. Manydifferent factors contribute to a climateof opinion, but in this case the Effective

Health Care bulletin looks to have made areal impactor at least to have benefited

from an extraordinary serendipity of

timing.

The ancient Greeks had a word

kairosfor doing things at the right

time. The Effective Health Care bulletin was

pushing at an opening door. But in a

highly debatable conclusion the authorsof this study suggest that producers of

guidelines should focus on those topics

for which the environment is likely to be

conducive to change and avoid ex-

pending effort in areas where change is

unlikely. We should remember that

powerful forces are at work to shape the

environment in which clinical evidence

is presentedincluding commercial in-

terests and episodes of spectacular un-

wisdom from factions in politics and the

media such as we are currently witness-

ing over MMR immunisation. Guideline

production, in common with other forms

of scientific activity, should not confineitself to picking winners. What do you

think? Whether you are a writer or a

reader, or just a weary recipient of guide-

lines, the journal would like to hear your

views.

Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:118

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Correspondence to: Dr D Keeley, GeneralPractitioner, Thame, Oxon OX9 3JZ;

REFERENCES1 Black N, Hutchings A. Reduction in the use of

surgery for glue ear: did national guidelineshave an impact? Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:1214.

2 NHS Centre for Reviews andDissemination. The treatment of persistentglue ear in children. Effective Health Care1992;1(4):116.

3 Dopson S, Miller R, Dawson S, et al.Influences on clinical practice: the case of glueear. Qual Health Care1999;8:10818.

Surgery for glue ear. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Impact of national guidelines on use

of surgery for glue ear in EnglandD Keeley. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Change in practice follows Effective Health Carebulletinposthoc or propter hoc?

To send a rapid response

Visit the website (www.qualityhealth-care.com), open the paper of interest,click on Submit a response andfollow the instructions on screen.

118 COMMENTARIES

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 115qs

5/6

SIMULATION FOR TRAINING ISEFFECTIVE WHEN . . .There is no question that simulation can

be an effective tool for training complexskills. There is some evidence that it

works.1 But it is only a tool. As with any

tool, in order to be effective it must beused appropriately. We commend the

paper by Satish and Streufert2 in this

issue of QSHC for highlighting the rolethat simulation may play in both train-

ing and assessment within the medicalcommunity, as well as the recognition

that effective simulation must: (1) be

built on underlying theory (they usecomplexity theory), (2) use structured

exercises, and (3) assess performance

and provide feedback. However, someadditional observations about simula-

tion are warranted so that scientists andtraining developers within the medical

community do not fall into some com-

mon myths and misconceptions knownto exist regarding training in general, as

well as the use of simulation fortraining.3 We therefore present a few

observations based on the science of

training1 4 and our experience in aviationand military environments about when

simulation is effective for training.5 6

Simulation for training is effective

when . . .

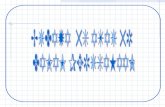

(1) . . . instructional features areembedded within the simulationSimulations to facilitate learning need to

be designed around key instructional

componentsthat is, simulation basedtraining must have a series of links that

create a learning environment (fig 1).One instructional strategy that has been

successfully used in aviation and mili-

tary environments and embeds theabove instructional features is the event

based approach to training (EBAT). This

strategy relies on the a priori embed-

ding of multiple events into the scenarioat different time intervals. These events

serve as cues for trainees to exhibit com-petencies targeted in training.7 In turn,

these cues serve as measurement andfeedback opportunities. Advantages to

this approach include:

ensuring opportunities to exhibit tar-geted behavior are presented;

scenario control while giving theappearance of a free flowing scenario;

increasing the ease with which com-petencies can be measured;

providing standardization across

trainees.Simulation can therefore only createopportunities for learning if instruc-

tional features are built into it.

(2) . . . carefully crafted scenariosare embedded within the simulationSatish and Streufert2 suggest that theSMS simulation can define scenarios a

priori. However, further clarification is

needed regarding the factors that drivescenario parameters. One must remem-

ber that, in simulation based training,

the scenario(s) are the curriculum sothey must be carefully storyboarded.This could be facilitated by performing acognitive task analysis (CTA). A CTAshould help in determining the contentof the scenarios since it will uncover thecues expected to be used to performcomplex tasks. In addition, scenariosshould build events into scripts. Theseinserted events serve as triggers and

provide known opportunities to bothpractise and assess important behaviors.Scenarios are therefore a key componentfor simulation to facilitate learning andcannot be left to chance or created with-out a learning outcome in mind.

(3) . . . the simulation containsopportunities for assessing anddiagnosing individual or teamperformance

As noted above, we agree with Satishand Streufert2 that simulation basedtraining will only be effective to theextent that trainee competence can beassessed. There are two points to this

statement.Firstly, simulation based training must

provide measurement opportunities thatease the burden on those responsible formeasurement. More specifically, simula-tions that use pre-scripted learner fo-cused scenario events not only ensurethat relevant competencies are beingassessed, but ease the assessment proc-ess as instructors know when key events

will occur.Secondly, not only does simulation

need to build in opportunities for theassessment of performance, but alsothese measurement opportunities mustprovide the basis for diagnosing skilldeficiencies. In other words, it is notenough that the simulation providesopportunities to capture performanceoutcomes, but it must also (as much as

possible) capture the moment-to-

moment actions and behaviors. Theseprocess oriented measurements are

much richer for training purposes; theyare also the most difficult to capture and

may require human intervention. Simu-

lations that include measurement sys-tems which only capture outcome meas-

ures (such as quality or quantity) do not

allow those responsible for training todiagnose performance; they do not offer

information on how to improve perform-ance. Performance measurement is para-mount to training and, without it, simu-

lations are just thatsimulations.

(4) . . . the learning experience isguided

We have all heard the saying practice

makes perfect. Similarly, it has beenargued that experiencethat is,

practicecan make an excellent teacher

because it generates knowledge within ameaningful context.2 The conditional

nature of both these statements needs toFigure 1 Components of scenario based training (adapted from Cannon-Bowers et al16).

T a s k s

K S A s

T r a i n i n g

o b j e c t i v e s

P e r f o r m a n c e

h i s t o r y

S k i l l i n v e n t o r y

F e e d b a c k

E x e r c i s e s

E v e n t s

C u r r i c u l u m

M e a s u r e s

M e t r i c s

Simulation for training. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Simulation for training is effectivewhen . . .E Salas, C S Burke. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Simulation can benefit the medical community by training bothindividuals and teams to reduce human error and promotepatient safety.

COMMENTARIES 119

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 115qs

6/6

be highlightedthat is, practice or

experience in and of itself does not equal

learning. Trainees who are given un-guided practice often:

learn the wrong thing;

do not focus on practising the rightbehaviors;

may spend too much time on only oneparticular aspect of training;

may not beable to transfer the skills tothe job.To maximize the learning experience,

practice must be guided (through care-

fully crafted scenarios and diagnostictimely feedback) so that trainees remain

focused on learning key competencies.

(5) . . . simulation fidelity is matchedto training requirements

When using simulations for training

purposes it is often assumed that more isbetter; this is not true. For example,

research has found that use of high

physical fidelity simulations in training

did not transfer or had very little effecton actual job tasks.8 Similarly, research

has successfully used low fidelity PC

based simulations to train complex indi- vidual and teamwork skills.912 The level

of simulation fidelity needed should be

driven by the cognitive and behavioralrequirements of the task and the level

needed to support learning.5

Finally, simulation for training is

effective when . . .

(6) . . . there is a reciprocalpartnership between subject matterexperts and learning/trainingspecialists

Learning is a behavioral/cognitive event.Training is about imparting longlasting

change in trainees. It is about creating acontext where key competitiveness can

be practised, assessed, diagnosed, rem-

edied, and reinforced. To do that requiresa partnership between task experts and

those who know about the design and

delivery of training. No one can do iteffectively alone. Both parties have

something to contribute: subject matter

experts articulate task requirements andneeds while training specialists createlearning environments. Both are neededand the medical community should fos-ter it.

CONCLUSIONSimulation is an effective tool for train-ing complex skills. The military andaviation environments have invested

heavily in simulation based training and,although further multilevel assessmentsneed to be conducted, initial data regard-ing its effectiveness are encouraging.1315

However, simulation is only a tool, andtraining developers and practitionersmust rely on the science of training tomaximize the effectiveness of it. Thereare known principles. Our recommen-dation is to apply them, and to develop apartnership with those who understand

what it takes to design and deliver effec-tive training.

Simulations must be designed so that:(1) instructional features are embedded

within the simulation, (2) carefully

crafted scenarios are embedded thatcontain opportunities for performancemeasurement and diagnostic feedback,(3) the learning experience is guided,and (4) simulation fidelity is matched totask requirements. Keeping all this inmind, the medical community can gaingreat benefits from using simulation totrain both individuals and teams toreduce human error and promote patientsafety.

Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:119120

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Authors affiliationsE Salas, C S Burke, Institute for Simulation &Training and Department of Psychology,University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL32826, USA

Correspondence to: Dr E Salas, Institute forSimulation & Training, University of CentralFlorida, 3280 Progress Drive, Orlando, FL32826, USA; [email protected]

REFERENCES1 Tannenbaum SI, Yukl G. Training and

development in work organizations. Ann RevPsychol1992;43:399441.

2 Satish U, Streufert S. Value of a cognitivesimulation in medicine: towards optimizingdecision making performance of healthcarepersonnel. Qual Saf Health Care2002;11:1637.

3 Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA, Rhodenizer L, etal. Training in organizations: myths,misconceptions, and mistaken assumptions.Personnel Human Resources Manage1999;17:12361.

4 Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA. The science oftraining: a decade of progress. Ann RevPsychol2001;52:47199.

5 Salas E, Bowers CA, Rhodenizer L. It is nothow much you have but how you use it:Toward a rational use of simulation to supportaviation training. Int J Aviat Psychol1998;8:197208.

6 Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E, eds. Decisionmaking under stress: implications for trainingand simulation. Washington, DC: AmericanPsychological Association, 1998.

7 Fowlkes J, Dwyer D, Oser R, et al.Event-based approach to training. Int J AviatPsychol1998;8:20922.

8 Taylor HL, Lintern G, Koonce JM, et al. Scenecontent, field of view and amount of trainingin first officer training. In: Jensen RS, ed.Proceedings of the 7th InternationalSymposium on Aviation Psychology.Columbus: Ohio State University, 1993:7537.

9 Gopher D, Weil M, Bareket T. Transfer of

skill from a computer game trainer to flight.Human Factors 1994;36:387405.

10 Jentsch F, Bowers CA. Evidence for thevalidity of PC-based simulations in studyingaircrew coordination. Int J Aviat Psychol1998;8:24360.

11 Prince C, Jentsch F. Aviation crew resourcemanagement training with low-fidelity devices.Improving teamwork in organizations:applications of resource management training.Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,2001: 14764.

12 Taylor HL, Lintern G, Hulin CL, et al. Transferof training effectiveness of a personalcomputer aviation training device. Int J AviatPsychol1999;9:31935.

13 Salas E, Burke CS, Bowers CA, et al. Teamtraining in the skies: does crew resourcemanagement (CRM) training work? HumanFactors 2002 (in press).

14 Holzman RS, Cooper JB, Gaba D, et al.Anesthesia crisis resource management: reallife simulation training in operating roomcrises. J Clin Anesth 1995;7:67587.

15 Barach P, Satish U, Steuffert S. Heealthcareassessment and performance. SimulationGaming 2001;32:14751.

16 Cannon-Bowers JA, Burns JJ, Salas E, et al.Advanced technology for scenario-basedtraining. In: Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E, eds.Making decisions under stress: implications forindividual and team training. Washington,DC: American Psychological Association,1998: 36574.

120 COMMENTARIES

www.qualityhealthcare.com